[Editor’s note: The following interview contains some spoilers for “The First Omen.”]

In the final act of Richard Donner’s iconic 1976 horror feature “The Omen,” star Gregory Peck — driven almost mad by the realization this his adopted son Damien is probably the Antichrist — heads to the Italian cemetery where Damien’s cursed biological mother is said to be buried. When he cracks open her grave, he’s not entirely surprised to find, not the skeleton of a young woman, but of a large jackal. After all, he’s already been told Damien is the product of a satanic breeding ritual between the devil himself and a willing female jackal.

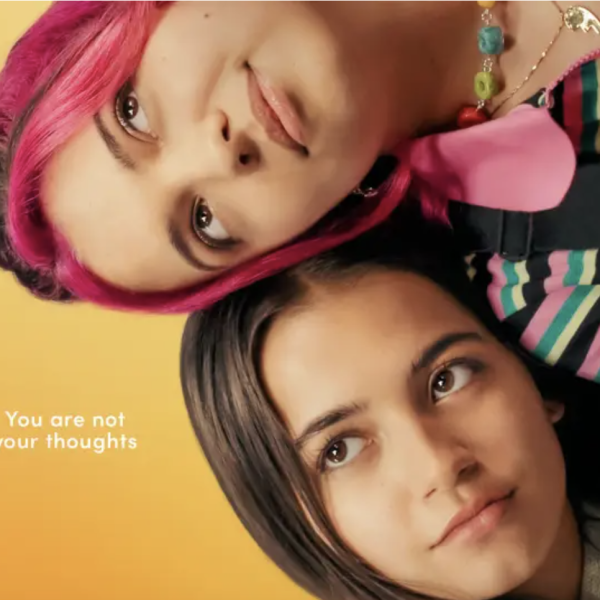

What Arkasha Stevenson‘s prequel feature “The First Omen” presupposes is: What if Damien’s mother wasn’t actually a jackal? In the pantheon of horror classic remakes and reimaginings — like “Halloween” and “The Exorcist,” to name some recent offerings — it’s a hell of a starting point. A smart one, too.

In Stevenson’s film, which she co-wrote with producers Tim Smith and Keith Thomas, we zip back to Rome in the mid-’70s. Young novitiate Margaret Daino (Nell Tiger Free) is about to take her final vows to become a nun, and she’s been invited to do so at the Italian church of her beloved mentor Cardinal Lawrence (Bill Nighy). She’s filled with excitement and good cheer, thrilled about taking the next step in her godly journey. Of course, what she finds in Rome is very evil indeed, like “oops, we’re trying to breed the Antichrist here, look away, sweet young sister” evil.

Both Stevenson’s vision and execution of “The First Omen” is refreshingly clever, putting some new twists on an old story, and honoring both in the process. But that doesn’t mean she didn’t take some major risks, right down to the very bones of the story. It’s a big and bold film for anyone, but especially for a first-time feature filmmaker like Stevenson, who previously worked in episodic television, like “Legion” and “Brand New Cherry Flavor.” How did this happen?

Asked this during a recent interview with IndieWire, and Stevenson laughed. “It feels very surreal, and it felt like I was getting punked when they did hire me,” she said of the pitching process she and co-writer Smith went through with 20th Century Studios which — and this is important — is owned by Disney.

“We pitched this through the lens of female body horror,” Stevenson said. “One of the big scenes that we pitched was the birthing clinic scene and the fact that we wanted to show a vagina on screen. I think that, maybe not that specific image, but coming at it with the vision of tailoring a story through the female perspective, and not wanting to shy away from the content or the imagery, help[ed] get us hired. That was really important to us, because this is a movie about rape, and it’s about female body autonomy. Disney was very excited to tell that story with us, which is like … what is that sentence?”

Let’s parse it: Disney was on board with a first-time director’s reimagining of a classic horror series that hinged on female body autonomy, couldn’t shy away from questions of rape, and was definitely going to include a vagina on screen.

“Everybody was on board,” she said. “Once we realized what the content of the film was that we were making, everybody realized that we couldn’t shy away from the imagery, especially with the timing of when we’re making this.” (The film shot in the fall of 2022, just a few months after the overturning of Roe v. Wade.)

Like many film fans eventually turned film directors, Stevenson admits she was probably “too young” the first time she saw some of her favorite (scary) movies. The first-time feature filmmaker grew up on “The Exorcist” and “The Shining” — “because that was the Valentine’s Day double feature on A&E every year when I was growing up,” she said — and credits her mom for steering her toward “The Omen” films.

“My mom saw that I loved ‘The Exorcist,’ and she was like, ‘Well, then you have to watch these other movies’ and, of course, ‘The Omen’ was one of them,” she said. Already an avowed Peck fan — she also grew up on Audrey Hepburn films, including the classic Peck/Hepburn joint “Roman Holiday” — young Stevenson was mostly thrilled to see one of her favorite actors, genre be damned. “I was introduced to horror without understanding what that meant, through the lens of genre,” she said. “I just thought I was spying on other people and their lives.”

For Stevenson, both then and now, that meant that the scary stuff felt rooted in the real world. “The scariest part of the original ‘Omen’ to me was when Lee Remick [who plays Damien’s adopted mother in the first film] is in bed with Gregory Peck and says, ‘I need you to call me a doctor because I’m losing my mind,’” Stevenson said. “That was so terrifying, this concept, which was very new to me as a kid, that you could lose your grasp on reality.”

Finding the line between reality and everything else was key to Stevenson, who wanted to blend the homegrown horrors of “The Omen” with some twistier stuff, like Roman Polanski’s “Repulsion.” “When we approached this film, we were thinking that we wanted to talk about where surrealism and realism meet, in a way that feels a little bit more like ‘Repulsion,’” she said. “This woman is in the midst of a conspiracy, but she doesn’t realize it because she’s constantly questioning her reality.”

No one was more delighted than Stevenson to discover that the same DP — the late, great Gilbert Taylor — shot both Donner’s “The Omen” and Polanski’s “Repulsion” (he also lensed “Star Wars,” “Dr. Strangelove,” and “A Hard Day’s Night”). She added, “It feels like these seeds were being planted early on in the process, and it just felt like a natural extension of that world.”

When Margaret arrives at the Vizzardeli Orphanage, she’s somewhat surprised to find that the institution — which only houses orphaned little girls, cough cough — also runs a birthing clinic for young Roman women pregnant out of wedlock. When one of those women starts giving birth, young Margaret is horrified to watch the process unfold, mostly because Stevenson and DP Aaron Morton lens the birth for maximum terror.

Stevenson said she always knew she wanted that full frontal shot of the young woman giving birth, complete with a demonic hand reaching out, instead of a fuzzy little infant head (at least, that’s how Margaret sees it). “That image is so important because that image is the theme of the movie,” Stevenson said. “It’s about the woman’s body being violated from the inside out. It’s about women being gaslit and completely vulnerable to their surroundings because they can’t trust their reality and then their bodies can be taken advantage of.”

Even with the heightened, truly out-of-body vibe of the shot, Stevenson was driven by a need for veracity. “We worked with Adrien Morot and Kathy Tse, and they are brilliant makeup effects artists, and they created this really gorgeous piece,” she said. “And the detail in that! There’s little bits of cellulite, there’s hair follicles. It was so beautiful, and I just wanted it to be that shot for five minutes.” (It’s not quite five minutes, but the shot certainly lingers.)

The MPA? Oh, they didn’t like it. “We went back and forth with the ratings board over five times, and it didn’t have to do with any of the gore, it just had to do with this image,” Stevenson said, noting the ratings board wanted to slap an NC-17 rating on the film for a shot that is distinctly not sexual. (The film is officially rated R, “for violent content, grisly/disturbing images, and brief graphic nudity.”)

Because of the studio’s unrelated request for further shooting coverage during the birthing scene, Stevenson and Morton had set up another camera to capture the side-view of the infant’s head crowning through Morot and Tse’s fake vagina. It’s as graphic and jarring as it sounds, and this happens in the first act of the film.

“The compromise [with the MPA] was to put that profile [shot] in and cut down on the frontal shot,” Stevenson said. “Strangely enough, I think the profile shot ended up being even more graphic and more disturbing, because you really see the violence of skin being stretched and pushed.”

It’s not the only scene like it in the film. Later on in “The First Omen” (and we’ll add in another spoiler alert here just to be safe, but let’s say, if you’re coming to see the birth of Damien, oh, you’re gonna see the birth of Damien), in which a female character undergoes a C-section to remove the planned spawn of Satan in a room full of people who have engineered this very event.

Stevenson is clear about the scene and what it means: “It is a live dissection; it’s another rape in the movie.”

She continued, “We wanted to not shy away from any of the imagery, and also really humanize the pain and humanize the flesh. A lot of what we did in that scene, and then also in the birthing clinic scene, was dropping out a lot of any other background noise or sound design, and really just [focusing on] the sound of the woman’s breath and her pleading, and occasionally layering on top other women’s breaths. It starts with one woman and her pain, and then can build into a collective cacophony of the women that were in the room previously.”

And even though there are other women present in that room, they’re not there to help. “You see all the people who are complicit and not doing anything, and also not reacting to her yelling for help,” Stevenson said. “I think that’s one of the most terrifying things to me, is that you think that people are going to help you when you’re in pain or in trouble, and probably nobody’s going to help you, you know?”

What’s scarier than that?

A 20th Century release, “The First Omen” will hit theaters on Friday, April 5.