After stealing the show at the VFX Oscar bake-off on January 13 at the Academy Museum, “Godzilla Minus One” has gone from sleeper to potential frontrunner. Director and VFX supervisor Takashi Yamazaki effectively emphasized how his small team of 35 artists completed 610 shots on a minuscule budget (reportedly $15 million for the entire production). He wowed the branch members with his demo reel of Godzilla’s fierce destruction, his creative ability to overcome his limitations, his graciousness toward his artists, and his dry wit.

Indeed, by outmaneuvering the other studio Goliaths with his underdog “Godzilla,” Yamazaki earned the biggest applause and now has momentum going into the nominations on January 23. His film has already grabbed more than $50 million at the U.S. box office, with a grittier black-and-white theatrical version set for January 26. No wonder one of the competing VFX supervisors proclaimed it the frontrunner after the bake-off.

For Yamazaki, “Godzilla Minus One” (from Toho Studios and Rocket Communications) was an opportunity to reimagine the legendary kaiju franchise with a more badass monster attacking 1947 post-war Japan. Little did the director realize just how timely it was, with coastal Japan rocked by the New Year’s Day earthquake following the coastal quake last May.

“I think it was a good decision to choose that era, with the almost apocalyptic state of Tokyo at the time,” Yamazaki told IndieWire. “Plus, Godzilla compounding the character’s troubles really put [them] at the bottom of the bottom in terms of character arc and development. So it was this act of climbing out from darkness that I think really tested the characters in many ways.

“In terms of what I wanted to do with ‘Godzilla,’” he continued, “I’m a huge fan of the very first 1954 ‘Godzilla.’ And to me, that film was a response to nuclear warheads and where the world was heading at that point in time. So Godzilla being this metaphor for nuclear warheads, I think, was very important to return to and not forget. During the production, it was both surprising and disturbing to see the state of the world unfold and reading the headlines because we were making a film about Godzilla and the subject matter it represents. And in some weird way, I feel, the timing of different Godzilla films, especially with the the context of Japan, it almost feels like this divine ritual or offering to the gods of some sort.”

Like Gareth Edwards (whose AI-infused sci-fi actioner, “The Creator,” is the perceived frontrunner), Yamazaki began as a VFX artist before becoming a director. His intent was to use cutting-edge CG to make his Godzilla fiercer and more photoreal-looking than ever before. The VFX was handled by Shirogumi (with Kiyoko Shibuya serving as visual effects director), using Maya for animation, Houdini for water simulation, and Nuke for compositing.

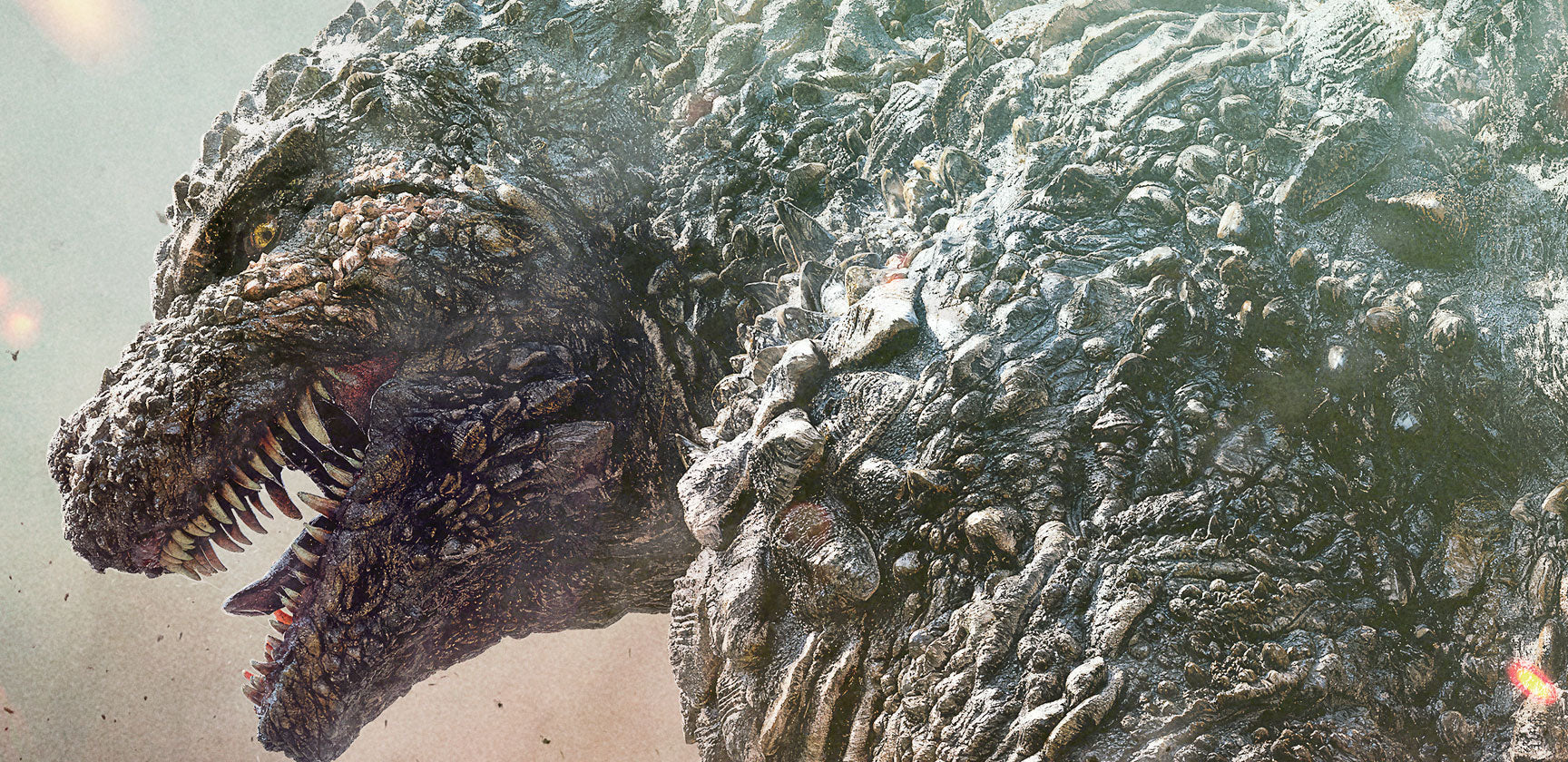

“The design of this Godzilla was done by myself, my artist [Kosuke Taguchi], and sculptor,” Yamazaki added. “And because we were working in digital space, it allowed for much more detail than what was possible with any type of handcrafted version. So we were able to increase the resolution of the scales, for example, and make them feel really, really sharp and give it this aggressive texture. And in terms of the bottom half of Godzilla, we made it feel very heavy and dense in a way that made the viewer feel like this mountain and triangular silhouette was walking and moving through a space. So imagine the [Imperial] Star Destroyer from ‘Star Wars.’”

Meanwhile, Godzilla’s face was a composite of the best features throughout the franchise, while the eyes were a golden almond shape. But it was important that the eyes never blinked to enhance the danger. In addition, the heat ray was more intense than ever before, and seeing it generated through the body was another nod to Godzilla being a nuclear weapon. However, making the heat ray blue to resemble nuclear particles was not part of the design process. “So we came up with that idea of the fins beginning to protrude and the color blue focusing on one point during filming,” said Yamazaki. “And, surprisingly, we had a good response. I know there’s a lot of YouTube reactions and people getting excited as you could tell that something was about to happen with the change in Godzilla’s body.”

They modeled the CG environments and Godzilla’s destruction of Ginza in post. The actors shot these sequences in a large parking lot with green screen backgrounds because they couldn’t afford full practical sets. What they did construct (food stalls, tents, the partial inside of a train) was on a very small portion of the road.

Fortunately, when it came to needing a World War II plane for the thrilling climax, they were able to construct a replica of a late-war prototype interceptor manufactured in Fukuoka, the Kyushu J7W1 Shinden (Magnificent Lightning), thanks to the Tachiarai Peace Memorial Museum in Chikuzen, Fukuoka, where the replica now resides. The surviving prototype referenced is currently displayed at The Smithsonian Air & Space Museum in Chantilly, Virginia.

“Initially, the budget didn’t allow for any portion of the [airplane] to be built,” added Yamazaki. But, thinking outside the box, having a plan B, we were able to find a museum that was willing to purchase the prop after the film was made, which offset the production budget it would have taken to produce the plane in the first place.”

The most difficult challenge, though, was the water simulation for the climactic battle at sea with Godzilla (requiring 150 shots). In fact, water initially didn’t play a substantial role until a young compositing artist, Tatsuji Nojima, who dabbles in water simulation in his spare time, showed Yamazaki some of his impressive results. It was then that the director rewrote the climax (in consultation with a military advisor) to attack Godzilla scientifically by wrapping him in a bubble and submerging him underwater, where the pressure would theoretically destroy him.

“The water simulation at the end was extremely difficult,” Yamazaki offered, “especially when Godzilla went berserk, moving around, performing a lot of action on the surface of the water. It put a huge strain on all of our rendering engines, so we created so much data in the process that when we added it all up it was easily over a petabyte. In the end, we erased the data from the scene where it was done, and made it while opening the hard disk.”

Yamazaki started with rough data and added more simulations depending on the force of surface water movement. Yet Nojima was so adept that Yamazaki was able to take final renders as they came in. “For each shot, we basically had one simulation that was happening on screen,” he said. “And, in order to do that, there were supposed to be two types of water, just the blue water surface movement, plus the white water.

“But I had to use a lot of techniques the way it looks underwater,” continued Yamazaki. “The amount of foam, as well as the amount of bubbles it would logically take to sink something of Godzilla’s scale, and how the sudden change in pressure would affect the surface of Godzilla as a creature. I thought a lot about how Godzilla’s body would change when it was pulled up, and how it would deal with the impact of the deep sea. I tried a lot of triangles to figure that out.”

Turns out this method was similar to the Oxygen Destroyer in the 1954 film, which Yamazaki forgot about. “It didn’t occur to me until after the fact,” he said,” when someone came up to me and made this comment because of the imagery, and the bubbles, and the Oxygen Destroyer. It was a happy accident.”