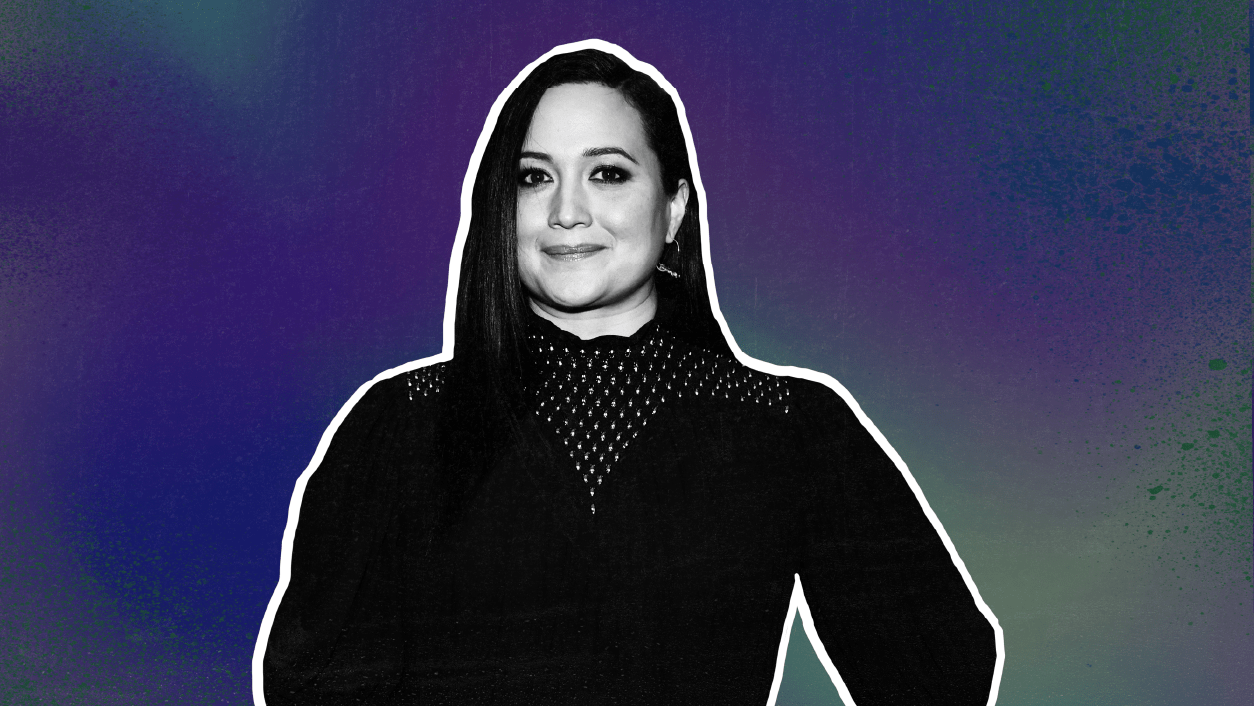

Editor’s note: This interview was originally published on December 5, 2023 as part of our 2023 IndieWire Honors ceremony package, which celebrated 11 filmmakers, creators, and actors for their achievements in creative independence. This interview has been lightly updated to reflect Lily Gladstone’s recent Best Actress nomination.

Lily Gladstone thrives on the unexpected. For instance, she’ll happily answer the usual questions — like, oh, what was it like working with iconic Hollywood actors like Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert De Niro on Martin Scorsese’s lauded “Killers of the Flower Moon”? — but she’ll really light up when you ask her something a little different. More like, what was it like working with so many fellow Native and Indigenous talents on that same film?

“It is incredible to have had [that experience] on ‘Reservation Dogs,’ it’s incredible to have had it on ‘Fancy Dance,’” she said during a November interview with IndieWire. “It was almost unheard of to have it on [a] Scorsese [film]. It changes the work entirely, just knowing that you have community all around you. I think a lot of us, when we work outside of Native-created spaces, a lot of times when we’re there, we’re the only one. Our voices exist in community. It’s a lot to put on one person to be the voice for such a large body, of a very diverse group of people.”

Even within the context of “Killers of the Flower Moon,” a production that includes a number of Native and indigenous talent both in front of and behind the camera, the Oscar-nominated Gladstone is tasked with much of the heavy lifting. The Montana-born actress, who is of Piegan Blackfeet, Nez Perce, and European heritage and grew up on the reservation of the Blackfeet Nation, stars in the film as Mollie Burkhart, a real-life figure who played a central — and tragic — role in the true story behind “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

Gladstone’s role in the film, her first major studio part, has already garnered her many accolades — including her first-ever IndieWire Honors award for her extraordinary performance in the film — and proves the indie darling’s profound skill. But she’s quick to turn the attention on everyone else who made her work feel so true, the people who asked (and answered) the kind of tough questions she loves.

For example, the actress has stayed close with some of the extras from “Killers of the Flower Moon,” many of whom she’s quick to note are actually Osage, including one named Erica Iron. All of them? They were part of the work, too.

“[Erica Iron] was going around and having every extra and every Native on set list their tribal affiliation,” Gladstone said. “At the end of the production, we figured there were over 200 tribes represented in that production. It was immense. It made the set feel very safe. It made it feel very fun. That was the thing that stood out to me, and I think particularly stood out in a surprising and new way to a lot of our non-Native cast and people on set. In between these moments of intense trauma, people are just enjoying themselves and laughing and loving being together. It’s how it is.”

The film closely follows the relationship between Mollie and Ernest Burkhart (DiCaprio) as a way into the Osage Nation murders that plagued the Oklahoma community in the 1920s. And while that story is filled with the aforementioned “intense trauma,” Scorsese also labors to show off fresh sides of the Osage, pushing back against the usual cinematic stereotypes.

“I think so much of film history has cast us in a very stoic light,” Gladstone said. “I love how we have these moments in the film where you see the bustle, you see the joy, you see the laughter, and then you see everybody settle into these tintype photos where you have to be very still and stoic. I think that’s where a lot of the perception has come from, is poring over historic documents of Native people instead of actually being around Native people. We are a very fun-loving group of folks. Same with ‘Fancy Dance,’ same with a lot of content on ‘Reservation Dogs,’ we talk about some really heavy historical traumas, but there’s always an element of humor. Even though the humor in Marty’s film is through his sense of humor, his lens, when Natives watch it, they pick up where we place it too.”

The film may be through Scorsese’s lens — albeit, a lens with prodigious Native information and input — but it’s Gladstone’s turn as Mollie that gives the film its heart. Asking any performer, let alone one tasked with such a complex role, how they navigated their character is a hefty query, but Gladstone answers the question with her characteristic thoughtfulness. How did she find her way to Mollie, her journey, her emotions, what was the path, I asked. Well, to begin, there wasn’t one path, not then, and not even now.

“It’s definitely a path that took a lot of turns,” Gladstone said. For starters, she said, it’s important to remember that in the Osage tradition, “Women own everything. It’s a patriarchal society in the sense that men often are the ones who are out there speaking for the people, but they’re always saying what the women want them to say. They’re always listening to what their mothers, their wives, their sisters are telling them. When it comes down to it, when families come together, the man moves to the woman’s clan, he moves to her village, he moves to her neck of the woods and becomes part of her family, even though she takes his name and he kind of becomes a representative for them. It’s still very grounded in the woman owning everything.”

Mollie is not some shrinking violet. She’s not inexperienced. She’s used to speaking her mind. She knows her history. The key to Gladstone’s performance is tied up in all of that, as evidenced by a story that Mollie references throughout the film, about the Osage story of the trickster (the “šǫ́mįhkase” or “coyote”), which is how she sees Ernest. The tale was originally shared with her by language teacher Chris Cote, and Gladstone recognized it as sharing many similarities with a Blackfeet tale she grew up with. These things tend to repeat themselves, both in life and in stories.

“The trickster in this case is very self-serving, very hedonistic, likes to feel good, and gets himself in trouble all the time, and in those stories never really wins,” she said. “Mollie, when she calls Ernest šǫ́mįhkase, she’s saying coyote, but she also means specifically that trickster figure and that dualistic nature. When you’re raised hearing these stories, when you’re a kid, they’re funny. As they age with you as a human, as a person coming into adulthood, you realize how important it is, because they hold these cautionary tales in them. … We always had to make sure there was a place where Ernest actions could hide in Mollie’s blind spots.”

Gladstone has seen the film three times. Like her co-star Cara Jade Myers, she sees something new with each viewing, including the things that did not make it to the screen. “A lot of the early takes that we did, we shot multiple ways because we weren’t entirely sure what the nature of this love story would be,” she said. “At one point, we did settle into what Ernest and Mollie’s dynamic [becomes], the one that was working the most, the one that [editor] Thelma [Schoonmaker] kept telling Marty, ‘We need more of that. We need more takes like that.’”

Mostly, Gladstone said, they played with the “different levels of suspicion” for Mollie, and the “different levels of complicity” for Ernest. “We decided that Ernest wasn’t physically abusive, because there was no evidence of that, and there were plenty of Osage women that were married to white men who were. The thing that stood out most when we were trying to solve this love story is, Ernest Burkhart learned Osage so he would be able to speak to Mollie on her level. A lot of white men married a lot of Osage women back then and never went to that length. So, there was something there. There was something that was stronger than just the money element of it.”

Still, tricksters are tricksters because they trick, they conceal, they surprise, they misdirect. Mollie sees that in Ernest, but can never quite allow herself to believe — at least, for a while — just how far he might take it. And there’s something else, too.

“There was also the element of her being not well,” Gladstone said. “I saw one person on Twitter point out, as a diabetic, how it feels to constantly need to be under the care of other people. As self-possessed, as independent as you can be, ultimately you have a capacity.”

In the film, we see Ernest “treating” the diabetic Mollie with a medication cocktail given to him by his uncle William King Hale (De Niro) and a pair of local white doctors who are in league with Hale and his nefarious plan. Ernest doesn’t know exactly what’s in it. Neither do we.

“In talking with the family, we figured it was most likely that Mollie was being given some cocktail of arsenic, morphine, and of course, her insulin,” Gladstone said. “Morphine shifts on a person. Sometimes it makes you hyper-aware, sometimes it makes you hyper-sedated. Arsenic is attacking your central nervous system and does long-term damage to it. And then of course, the insulin, which was doing its work and was working against the diabetes. So, as everything’s shifting, there’s just a long period of time where Mollie doesn’t really have her head about her. A lot of her suspicion is coming up subconsciously or moments where you’re starting to put it together, and your heart uproots any seeds of doubt that are being planted. It’s complicated, all of it’s very complicated. And all of it was very true.”

She added, “It would be easy to say, as we kind of wanted to suspend in the film, that Mollie didn’t really know what was going on. Mollie was really aware of what was going on, but she was in an incredibly dangerous place. It really wasn’t until she had armed guards around her that she was safe enough to move forward.”

Gladstone said she closely studied Philip Seymour Hoffman’s work in “Doubt” for the final act of the film to capture the painful dichotomy of knowing a horrible truth but being unable to fully reconcile it with how you feel. “It was important that the audience be able to see the love that was still there,” she said. “If you break it down, the FBI did talk to Mollie Burkhart, did speak at length with her, did help her put these things together. When Mollie herself was in cross-examination, she said she just wanted the truth to come out. She didn’t want any harm to befall her husband, but she just wanted the truth. After the trial and after Ernest had gotten out of prison, because he would not spend very long there, he moved back to Osage country, and it was said that they spent time together even after he got back.”

Still, Gladstone noted that the real Mollie did sue the real Ernest before she died, and even got some money back from him, funds that were mismanaged by him during the period in which he was her guardian. (She also sued Pitts Beatty, her previous guardian; she got about $14,000 from Burkhart, about $7,000 from Beatty.)

“When she passed away, she was no longer an ‘incompetent Osage,’ that [designation] had been lifted,” Gladstone added. “She was fully responsible for her own money. So, Mollie had a story after. When I watch the end of the film, I can see how most audiences will take it at face value, just blinded by love. Mollie had an agenda at the end too. It doesn’t mean that the love didn’t go anywhere. She was breaking an addiction she didn’t know she had. She’d likely been given morphine for a long time. There’s multiple addictions being broken at the end there.”

By the end, Gladstone said, she saw Mollie’s relationship with Ernest coming right back around to the coyote story. She even told Scorsese she saw the film, not as a Western as so many people term it, but something new, “Trickster noir.” “At the end, she calls him out for it again,” she said. “And really, that puts her as a figure in this trickster story too. In these stories, even if the trickster doesn’t ultimately win in the end, doesn’t mean that their self-serving nature hasn’t hurt a lot of people along the way, hasn’t changed some origin stories for the way the world works.”

While Gladstone is picking up the bulk of her accolades for her work on “Killers of the Flower Moon,” the attention has also allowed her to chat up her other films from this year, including Morrisa Maltz’s “The Unknown Country” (which garnered her a Gotham Award in November) and Erica Tremblay’s Sundance premiere “Fancy Dance,” which just Tuesday was picked up by Apple after nearly a year in limbo.

“I’m so proud of my indie work. In this incredibly loud year, I’m just so happy to be able to talk about the three that I have in circulation in addition to ‘Killers of the Flower Moon,’” she said.

It’s not just cinephiles, Gladstone completists, indie film fans, and Gotham voters who revere Gladstone’s “smaller” work either: it’s where Scorsese himself first found his eventual star. Like many of her admirers, Scorsese first got hip to Gladstone’s considerable charms after seeing her breakout turn in Kelly Reichardt’s “Certain Women.” That Scorsese found her in an indie is of particular import to Gladstone.

“It makes me happy that Marty’s watching Kelly’s work,” she said. “Because every time that he brings up [that he saw me in ‘Certain Women’], he also shouts out how much he likes her work. Kelly is the kind of filmmaker I always dreamed I would be able to work with, [starting] when I saw ‘Wendy and Lucy.’ … I’m really, really happy that Marty, who is the walking encyclopedia of film history, is a Kelly fan.”

And, despite recent headlines to the contrary, Gladstone has no plans on leaving indie film. A May interview with The Hollywood Reporter was framed around an anecdote about Gladstone seeking out non-acting work opportunities during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic — the headline said she “almost quit the biz,” though the actress didn’t say that exactly — and she was eager to correct the assumption she was on the way out of the business before Scorsese plucked her out of indie obscurity. As ever, Gladstone knows the context matters.

“I’m not going to say it was taken out of context, it was very in context,” Gladstone said, again noting it was during the early part of lockdown, the summer of 2020. “I was coming to terms with the fact that my slow burn independent work was not moving at the pace that my life needed to keep up with.”

She knew, for instance, that Tremblay — who Gladstone had previously worked with on the short “Little Chief” — was writing “Fancy Dance” for the actress. “We touched base several times over the summer and I knew that something was coming,” she said. “I read an early, early draft, … I knew that those things would be on the horizon. Any time Erica calls, any time Kelly calls, any time these people that I would want to work with, I would answer the call. But at that point, the pace of my career was one film a year. And then, starting to speckle in a TV episode here and there, which was so fun and helped me expand everything.”

But it was a different time, and Gladstone had new obligations. “I was living at home with, at the time, four elders, my grandmother has passed away since then,” she said. “I wanted a job that would soothe a little bit of the unrest in my soul about all of the injustices going on in the world, especially at the time. Things reached such a fever pitch in 2020, I was watching a lot of my friends who were going to a lot of these protests, and even though they were masked, hearing about people who were getting COVID from showing up to show support after George Floyd. And I was just stuck at home, because I was so terrified of bringing something home and making my family sick. My whole family was incredibly vulnerable to COVID. I was wanting to do something that would serve a greater purpose.”

Enter: bees. “I have a very strong love of bees, particularly bumblebees, and I’d seen that viral video of the Asian giant hornet, ‘murder hornets’ as we came to call them, just wiping out an entire colony of bees,” she recalled. “They’d moved into Washington, they were in the county north of where I was living. I had been already examining things that I could do from home and bring some money in, particularly to help my parents and grandma with the mortgage, and that was something that struck me: the Department of Agriculture was [offering] three grand a month [to track the murder hornets], seasonal work that was flexible enough when I was ready to go back to work.”

She even remembered thinking to herself that such a gig would make for a “badass Kelly Reichardt film, someone who’s just out in the field trying to trap these big bugs.” But she wasn’t going to leave acting altogether, she said, she just needed to make some money and use her spirit for some sort of good during a fraught time.

“I know it’s glamorous to say I almost quit acting altogether, and of course every actor is going to say that you feel like doing that sometimes,” Gladstone said. “It requires a lot of sacrifice, it requires a lot of compromise. At that point, I was just really wondering how I was going to be able to do much of anything, like a lot of people during COVID were.”

That Gladstone would want to spend her time doing something for the greater good isn’t surprising. She’s continued to use that inclination even in the midst of awards season. After the actors’ strike ended for instance, Gladstone’s first public comments about the film weren’t the usual stuff, the easy answers, the soft questions. It was a Twitter thread about how the film might impact members of the Native and indigenous communities.

“I had time to consider it, I had written different versions. Different elements of that thread that I wrote had been written over the summer, shortly after the strike went into effect,” she said. They were able to screen the film for an all-Osage audience on July 8, less than a week before the actors’ strike began, which provided further invaluable insight to Gladstone.

“I’ve had time to acclimate how this film is shot, what it depicts, Osage have grown up hearing this, but seeing it on film is triggering,” Gladstone said. “But the history itself is triggering. A lot of people felt like it was depicted very well. It didn’t shy away from the reality of the violence, but it didn’t make it a gratuitous, in-your-face, filmic thing either. It was balanced and a lot of people appreciated that. It doesn’t mean that first-time audiences, particularly ones that don’t specifically know this story and have had time to acclimate to that, aren’t going to have that reaction. … When you bring Native women to the heart of the story and the audience gets to fall in love with them a bit, it hits so much harder. When you’re humanized in a story, in a history that is by nature dehumanizing you and your people, it hits harder.”

Having the extra time to ruminate on the film and its impact made one thing clear to Gladstone: she felt compelled to advise her friends to, at the very least, not go see it alone. “‘Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour’ came out at the same time, and a lot of times, [in the theater] next door, when these things are happening, you’re hearing all the Swifties singing along to the music,” she said. “Which is great, good on them, they don’t know what’s going on in this theater. But it’s two very different experiences.”

Her instincts have proven to be right. “A lot of my close Osage friends have gone back to see the film in theaters with an open audience,” the actress said. “It’s Oklahoma, there’s a lot of people there who still harbor some really ugly sentiments about Native people, who are in the audience expecting to watch ‘Goodfellas’ and who are vocally sighing or giggling when something happens. They’ve said it, actually, when you see it without community, it can be a pretty triggering experience. Broad audiences aren’t sensitive to this being something bigger than just a movie.”

But it is bigger than just a movie. It’s much bigger, and Gladstone centers that thought whenever she speaks about the film and her work in it.

“All of the native response, particularly from Native women, is what I care most about, is what is so valid,” Gladstone said. “I do love the film that we made. I’m so proud of the film we made. I’m so grateful that so many Osage people who worked on it and people who didn’t work on it feel proud of it too. It may not be the movie that a lot of Osage would’ve made, but it was a movie that a lot of Osage had a huge hand in making. A lot of people that you’re close to are telling you they want to see it, they’re not sure if they’re ready. And it’s just important to say, ‘That’s OK.’”

It will be there for them when they are ready. So will Gladstone.