I am not a “spiritual person.” I only believe in God during bumpy flights and New York Rangers playoff games, I only go to temple to make my mother happy, and I only believe in life after death because the movies — photographs and video of any kind, really — allow us to summon our most beloved ghosts at will. In that light, it should come as no surprise that I’ve never placed much faith in the work of psychics or seers, even though New York seems to have two storefront fortune tellers for every Starbucks (I roll my eyes at both, but only buy $5 rice krispie treats from one). And yet, I suppose it should also come as no surprise that only a movie could have the power to convince me otherwise, or at least to make me better appreciate the nature of what psychics do and the mutual need they share with the people who turn to them for peace of mind.

It certainly doesn’t come as a surprise that said movie, “Look Into My Eyes,” was made by “Miss Americana,” “The Departure,” and “After Tiller” director Lana Wilson, a singularly perceptive filmmaker whose documentary work has always focused on the various ways that pain can web people together — if only because it can’t be exorcized alone. In her wildly overachieving portrait of Taylor Swift, which continues to tower above the endless stream of publicity-driven concert movies and biodocs that other musicians have commissioned since, Wilson explored how an arena-sized pop concert might serve as a stage for personal catharsis.

That emphasis on performance continues with her skeptical, mesmeric, and ultimately rather moving “Look Into My Eyes,” which flips the script by examining Wilson’s favorite topic in far more intimate terms. Once again, the filmmaker hones in on an unbelievable talent. This time, however, there’s a good chance you literally won’t believe it. And that’s OK, because at no point does Wilson make even the slightest effort to convince us that any of the seven kooky psychics we come to know over the course of her movie actually have the power to commune with the dead.

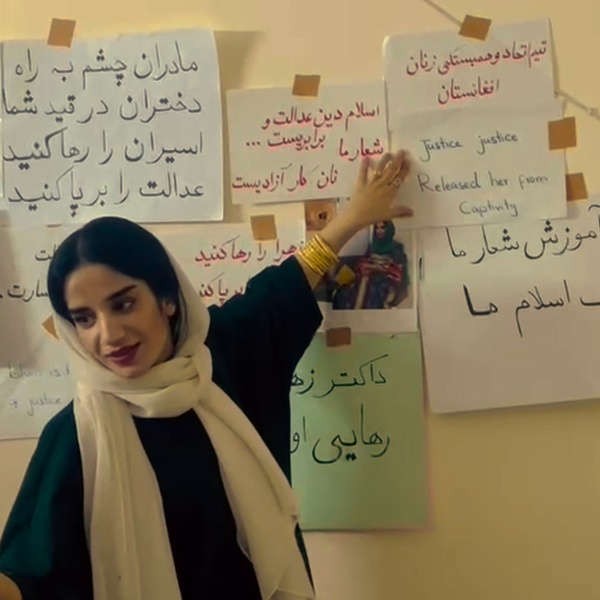

It turns out that that isn’t really the talent in question. These people have developed a gift of a different kind, one no less valuable to the strangers who come to their spartan office spaces for private readings. What they have is the ability to sit across from someone they’ve never met before and show them a clear — and often reassuring — reflection of their greatest anxieties. Yes, the spirit of your late father is smiling from the other side when you read your daughter her favorite book. Yes, your Chinese birth mother still thinks about you (even if she isn’t particularly emotional about it). Yes, your dead cat is happy in cat heaven.

The clients in “Look Into My Eyes” aren’t holding out for hard proof. They’re merely searching for the permission they need to believe in the half-truths that make it possible to live with loss. And loneliness. And the helplessness that comes with not knowing what happened to somebody, what you should do, or why your dog refuses to wear his stupid fucking leash. It’s a permission that neither these psychics nor their customers can give to themselves, but that avails itself to them both in the suspended disbelief shared between them. As Wilson points out in the film’s press notes, and as the subtle but slyly effective meta-commentary she weaves into the film itself makes clear: At the end of the day, going to a psychic isn’t all that different from going to the movies; both experiences invite us to sit in the dark, lower our guards, and allow fictional stories to inspire the very real feelings that we struggle to conjure on our own.

Entrancing from the start but slow to reveal the full scope of Wilson’s vision, “Look Into My Eyes” locks into that furtively cinematic essence by framing its psychic readings with a stiff naturalism that recalls the interview scenes in Hirokazu Kore-eda’s “After Life.” For more than 20 music-free minutes of hushed conversation, the film cuts between a series of different sessions to establish the vibe — no Christmas lights and crystal balls, lots of closed eyes and therapy-coded language — and make room for our skepticism. A nurse wants to check in on a young patient who died in her arms several decades earlier. A man is eager to know if his late father is making his presence known. One woman is curious if she’ll ever come into money, another if she’ll ever have hens. It isn’t long before the specifics begin to blur into a numbing pall of sadness and eccentricity. And just when you start wondering how Wilson will be able to keep this interesting for almost two hours, she breaks the spell and follows one of the psychics home.

Surprise, surprise: He’s a frustrated actor who’s obsessed with his cat — he has a T-shirt with Mr. MacDuffy’s face on it — and claims to have experienced paranormal activity in his house, which is enviably spacious even though the press notes insist that all of these psychics charge on a sliding scale and have to maintain day jobs in order to pay the bills. In fact, almost all of Wilson’s subjects have a pronounced interest in the performing arts. One of them is a low-key hoarder who dabbles in screenwriting, weeps at even the passing thought of “Central Station,” and otherwise expresses himself through the music of The Beatles. Another wrote and starred in a one-woman show about her life. One woman is happy to say the quiet part out loud by admitting that she makes the most of her theater degree through her work as a psychic. Phoebe — who specializes in communicating with animals — is deeply obsessed with John Waters.

It’s probable that many New York psychics aren’t like this, but Wilson makes great use of the ones who are. She mines them for their emotional legibility, and for their willingness to recognize the performative nature of their work. “Most people who enter into this feel like they’re making this shit up,” one of her subjects admits, “and then proof happens.” I suspect it’s the same “proof” that a playwright experiences when one of their shows gets its first laugh or round of applause. That same subject also likens psychic readings to improv comedy because she never really knows what sort of nonsense is going to come out of her mouth.

Some of the fortune tellers wear their self-doubt a bit more heavily, with one of them going so far as to shatter the fourth wall at a key moment that Wilson positions at the film’s midpoint point in order to formally recognize our skepticism so that she can leverage it into a nuanced and surprising portrait of belief. I was a little awed by the discipline and control with which Wilson gradually zooms out on her subjects over the course of the movie, as the ever-widening scope of her documentary makes room for us to find our own truth in all of this fiction (disabusing us from any of the condescension we might bring to her subjects in the process).

If the second half of “Look Into My Eyes” is more tender and relatable than its first half would ever have led me to expect, that’s because of how sensitively Wilson plays on the idea that her psychics need to believe in themselves — and each other — more than we need to believe in them. “Sometimes I believe healers need the most healing,” one of them says, and Wilson doesn’t shy away from unpacking their trauma. Phoebe’s relationship with her father explains a lot. So, too, does a colleague’s minute-by-minute memory of a loved one’s death, which she’s since immortalized as an ornate tattoo on the inside of her arm.

Perhaps nothing tells us more than the fact that many of these psychics see psychics themselves, and a climactic scene in which Wilson assembles several of her subjects for a group therapy session coheres this occasionally scattershot film around the idea that everyone is looking for solace on their own terms. It doesn’t need to be real in order to feel real, but if it feels real then it might as well be. After all, movies themselves are the stuff of pure illusion, and they were only even more convincing when their movement itself was a trick of the light (impractical as it would have been to shoot “Look Into My Eyes” on film, few docs would have been so thematically enriched by the format). And as the movies remind us better than any other medium, sometimes people are a lot closer to us after their deaths than they ever could have been — or than we ever allowed them to be — when they were alive.

Grade: B+

“Look Into My Eyes” premiered at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival. It is currently seeking U.S. distribution.