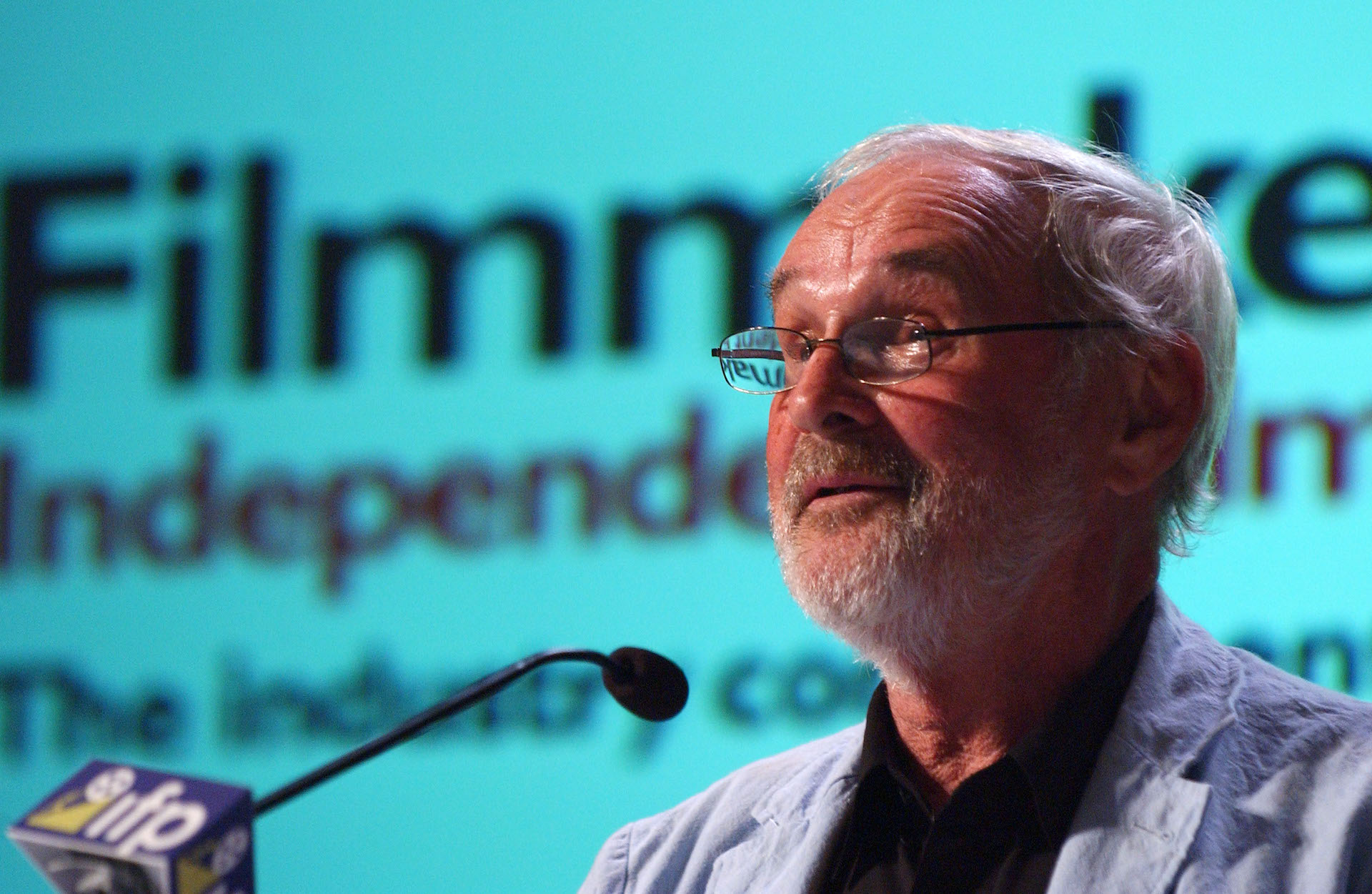

Norman Jewison is dead at the age of 97. For over four decades he sustained a career of films that became major box office hits as well as others that presented current social issues in a Hollywood context (with some combining the two). He died peacefully at his home on Saturday January 20.

“In the Heat of the Night,” which beat “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The Graduate” for the Best Picture Oscar for 1967, is the most obvious example of Jewison’s talent for turning tough subjects into hit movies. It grossed (adjusted to current prices) over $200 million, with it already having become a major success before it won five Oscars (Rod Steiger for Best Actor and Adapted Screenplay, though not Best Director). Ironically, the racially-charged story about a Northern Black detective (Sidney Poitier) investigating a murder and confronting a racist Southern police chief wons its Oscars in a ceremony delayed by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Norman Frederick Jewison was born on July 21, 1926 in Toronto, Ontario. His father operated a retail business. His early school years included signs of his interest in the performing arts. His education was interrupted by service in the Canadian Navy during World War II. He then graduated from the University of Toronto in 1949, where he was an active participant in multiple theater productions.

As was not unusual for budding Canadian directors at the time, he initially pursued his early interest in London, though with limited success. He returned to Toronto and was recruited by the newly formed television branch of Canadian Broadcast Company. He advanced quickly to direct a range of productions across multiple genres and presentations. In 1958, he was hired by NBC in New York, where for several years his most notable work came in musical specials. These included Judy Garland’s iconic 1961 comeback show, the success of which elevated him and led to feature films.

He started off with four comedies with Universal, beginning with “40 Pounds of Trouble” in 1962 with Tony Curtis (for the actor’s production company), then through 1965 working with major stars like Doris Day, Rock Hudson, James Garner, and Dick Van Dyke, and Tony Randall. But when he replaced Sam Peckinpah early in the filming of “The Cincinnati Kid” starring Steve McQueen he began an elevation that led to the strongest period in his long career.

Starting with “The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming” (1966), with the sole exception of “Heat,” Jewison also produced all his films. “Russians,” a major hit for United Artists, with the unknown Alan Arkin starting a long career, was the first of Jewison’s five films to be Oscar Best Picture nominated.

From “Heat” forward for at least 20 years, each new Jewison film was considered a major important production, though with varying responses. Several hits followed quickly, starting with the stylish (and visually inventive) “The Thomas Crown Affair,” one of five films of his edited by future director Hal Ashby (who won an Oscar for work in “Heat.”)

The two men’s talents combined to create (along with actors Steiger,Poitier, and Larry Gates) perhaps the most famous moment in Jewison’s career: The iconic scene of a Black man returning the slap of a wealthy white Southerner without hesitation stunned (and in most cases thrilled) late 1960s moviegoers not accustomed to seeing actions like that presented.

Jewison’s sense of racial justice, indeed a wider awareness of societal prejudices came early in his life when as the son of Protestants in then-nearly all white, Christian Toronto his name evoked taunts of anti-semitism even though he wasn’t Jewish. Post-military service, he encountered the scourge of American segregation as he hitchhiked across the South.

Those and other experiences influenced perhaps his pursuit of social-issue themes in some of his films — a dystopian corporate future (“Rollerball”), labor unions (“F.I.S.T.”), a flawed legal system (“And Justice for All…”), other Black-themed stories (“A Soldier’s Story,” “The Hurricane”), the neglect of veterans (“In Country”), the Holocaust (“The Statement”). With “Fiddler on the Roof,” he was the gentile director of possibly the most-anticipated Jewish-themed story of its time (and also his biggest hit).

One major contemporary story that escaped him was “Malcolm X,” for which he was the original director. Spike Lee, coming off the acclaim of “Do the Right Thing” spoke out about the appropriateness of having a Black director, and with Jewison’s support ended up making the film.

But he never took his eye off of making mass-audience entertaining films. “When I make a film, I never want the film to become a vehicle for social propaganda. If I wanted to do that, I’d make documentaries.” “Moonstruck,” his second-biggest hit in 1987 (he last breakout success) became of the biggest romantic-comedies ever, and accounted for the two other acting Oscars from his films (Cher and Olympia Dukakis).

Other significant films among his credits were “Jesus Christ Superstar,” “Best Friends,” “Agnes of God,” and “Other People’s Money.” As producer only, his credits include “The Landlord” (Ashby’s debut film), “The Dogs of War,” and “Iceman.”

Actors he directed include Carl Reiner, Edward G. Robinson, Ann-Margret, Eva Marie Sainte, Lee Grant, Faye Dunaway, Melina Mercouri, Topol, James Caan, Ralph Richardson, Sylvester Stallone, Al Pacino, Burt Reynolds, Goldie Hawn, Denzel Washington, Howard Rollins Jr., Jane Fonda, Anne Bancroft, Meg Tilly, Nicolas Cage, Bruce Willis, Emily Lloyd, Danny De Vito, Gregory Peck, Robert Downey Jr., Marisa Tomei, Whoopi Goldberg, Gerard Depardieu, Michael Caine, Tilda Swinton, Alan Bates, and Charlotte Rampling.

Though his films were nominated for 41 Academy Awards, winning 12, he personally never won a competitive Oscar. He was awarded with the Irving Thalberg Award for his achievements as producer. Other awards include his naming as a Companion in the Order of Canada, a life achievement award from the Directors’ Guild of America, the New York Film Critics’ Best Film prize for “Heat” (which was presented to him by Sen. Robert Kennedy, who he met on a ski vacation and encouraged him to make the film).

He maintain a Canadian primary residence throughout much of his career (and provided his rural farm as a site for a luncheon during the Toronto International Film Festival some years). He was committed to the advancement of Canadian film culture, led by his founding of the Canadian Film Centre in 1988 as a school for training professionals in cinema, television, and digital media across multiple professions.

Jewison was married to Margaret Ann Dixon from 1973 until her death in 2004. He is survived by Lynne St. David-Jewison, whom he married in 2010. Other survivors include three children from his first marriage and five grandchildren. His autobiography “This Terrible Business Has Been Very Good to Me” was published in 2005.