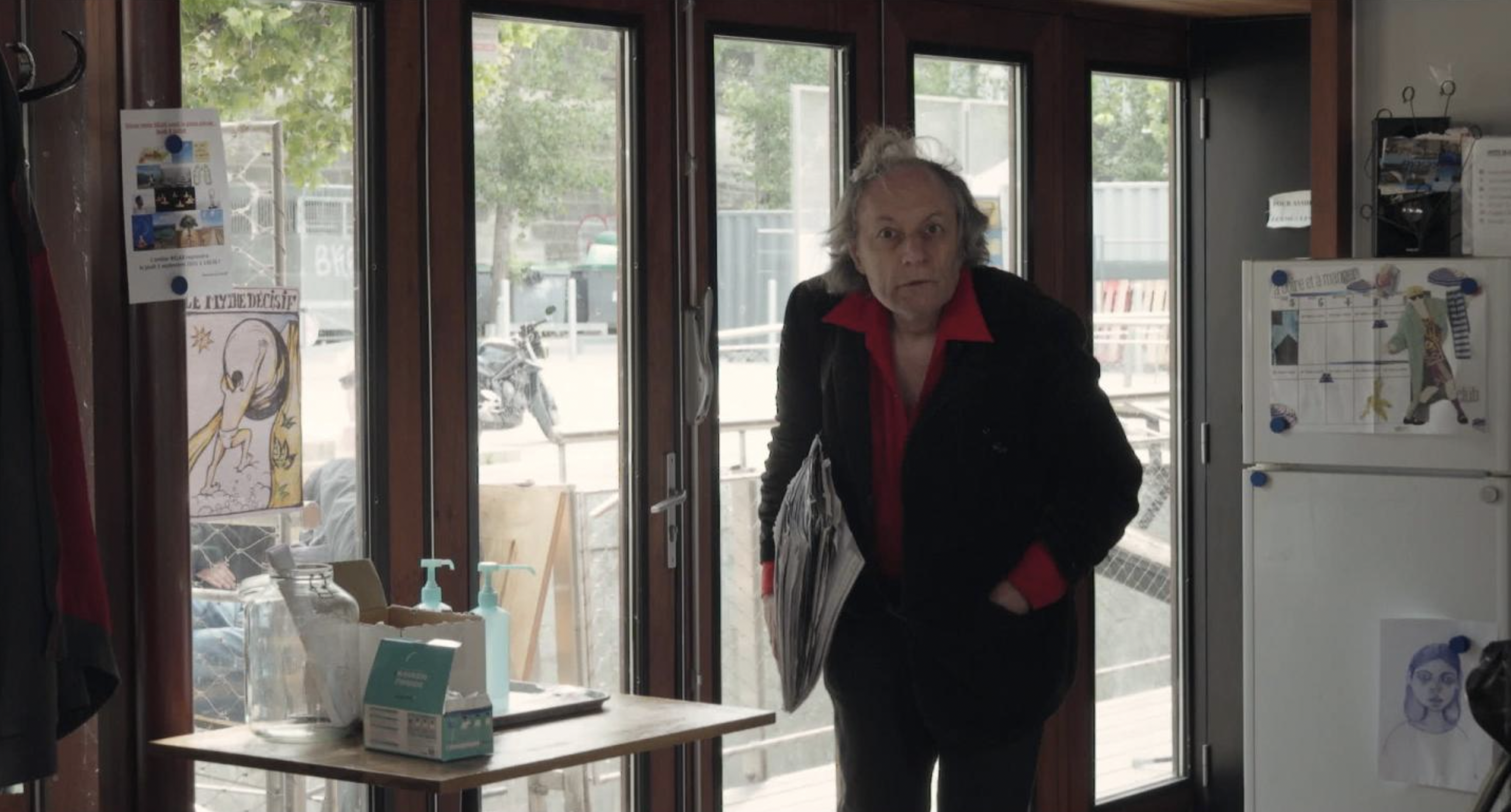

The first thing you notice about the Adamant is that it’s absolutely beautiful — not just for a psychiatric facility, which tend to resemble prisons or kennels, but for a building of any kind. A floating barge moored on the right bank of the Seine (where it’s surrounded by a labyrinth of unfeeling concrete towers), this self-contained wing of the Paris Central Psychiatric Group sticks out of the landscape like an antique cabinet that was accidentally dropped into the middle of an Ikea showroom; it’s hard to shake the feeling that someone might notice the error and scoop the whole thing right out of the water at any moment.

And yet the barge’s oak brown wooden slats continue to creak open every morning, music to the ears of local men and women whose mental disorders have left them nowhere else to go. Unlike so many other day centers like it, however, the Adamant refuses to act like a last resort. Staffed by plainclothes health specialists and home to art workshops, a screening room, and a café that’s run by some of its most loyal customers, the Adamant is both a safe haven and a thriving community unto itself. Their attendance may be prescribed, but its patients want to be there, and that makes all the difference to their dignity.

Mental illness so often becomes a double blind that can make people appear invisible to the world (and themselves along with it), but the Adamant — absent the visual signifiers of psychiatric treatment — encourages visitors to see themselves beyond and in spite of their condition. It reminds them that mental illness is a condition they have, not the defining element of who they are. The only ambition of Nicolas Philibert’s Berlinale-winning “On the Adamant” is to extend that view to a wider audience; to gently, almost imperceptibly challenge the idea that “madness” should be kept out of sight from polite society when it can’t even be siloed away from the beautiful things in our own mind.

Wiseman-esque upon first blush, but absent a broader institutional focus on French psychiatry (along with anything else that might challenge the magic of the Adamant’s method or clarify the last-minute implication that the center is under threat), Philibert’s fly-on-the-wall documentary is all the more effective because the director refuses to pretend that he isn’t visible — not in this place where people come to be seen, and not merely looked at. Long stretches of strictly observational cinema allow us to absorb the rhythms of day-to-day life aboard the Adamant, and to familiarize ourselves with a small handful of regular patients, but Philibert best affirms the facility’s methods by allowing his subjects to directly address the camera.

One of them has a lot of questions about the equipment, and whether it’s fair that Philibert’s assistant should have to carry it. Another insists that all of the patients are “actors without realizing it.” In a different circumstance, that comment might sound like an accusation (Philibert was unsuccessfully sued for exploitation by the subject of 2002’s “To Be and to Have”), but here it feels almost laudatory, as if the patient is acknowledging how the director’s presence feels like a natural outgrowth of an environment where creativity is used to pierce the worst assumptions that might make about one another. Or, as Philibert phrases it in a closing scrawl that puts his thumb on the scale more than Wiseman ever would: “To keep the poetic function of mankind and language alive.”

Somewhat shapeless in its design (the film doesn’t seem to follow a strict chronology, and a few errant masks are our only indication as to when it was shot), “On the Adamant” spends much of its running time watching patients discuss and/or explore their relationship to the arts. One is a gifted illustrator, another a dedicated guitar player; the documentary opens with a man named François performing a spirited rendition of the 1979 rock song “Le Bombe Humaine” by the French band Téléphone, the lyrics of which allow his deepest frustrations to command the attention they deserve. These characters don’t have clear arcs, per se, but they help instill a vivid sense of community.

Later, the patients put together a film festival where they decide to program Abbas Kiarostami’s “Through the Olive Trees,” though the scene reveals less about that choice than it does the agency of all people aboard the Adamant, where patients are involved in balancing the café budget, and whose very design was created with input from the people who the facility was built to help.

“On the Adamant” doesn’t make any claims to be representative of France’s mental health system at large (in fact, the film is the first installment of a trilogy that will explore different facets of the country’s approach to psychiatric care), but Philibert still risks painting a misleadingly idyllic picture of what it’s like to live with schizophrenia, severe OCD, or any of the other conditions the film refuses to classify. We’re never told if patients have to meet any particular criteria in order to be allowed onto the Adamant, and while several of them openly discuss the positive benefits of their medications (without which one man says he thinks he’s Jesus, “surrounded by little birdies up in heaven”), it’s unclear whether those medications are a requirement for admittance. There are no violent outbursts, nor anything more aggressive than the fleeting glimpse of an argument. Quiet heartbreak abounds (“Mentally sick people have no family,” one patient declares), but the only sign of immediate trouble comes when the resident bohemian suddenly implies that he and his brother were the inspiration for “Paris, Texas.”

But this isn’t to suggest that Philibert has left the more difficult moments on the cutting room floor, or — in defiance of his film’s central message — to insist that mental illness has to look a particular way in order to be recognized as such. On the contrary, it’s only to say that “On the Adamant” is less interested in highlighting the more overt symptoms of mental illness than it is in drawing attention to the reservoirs of humanity that tend to disappear behind them, even though they run so much deeper than the conditions that hide them from sight.

This is an unforced — and sometimes unfocused — film that emphasizes ambient empathy over instructional rhetoric; by immersing viewers in a facility where the patients can be impossible to distinguish from the staff, Philibert places his faith in the idea that audiences will naturally come to distrust the stratification of a social framework that’s determined to dehumanize people for their differences.

What “On the Adamant” lacks in memorable episodes it makes up with its emphasis on the space between them, which like the space between people is smaller than we think, and like the space within people is richer than we can imagine. As one of the patients says when discussing his latest piece of artwork with the rest of the drawing class, “You’re free to see what you want.” It’s a freedom that many of us surrender all too willingly, and one this film is determined to restore.

Grade: B

Kino Lorber will release “On the Adamant” in theaters on Friday, March 29.