There’s an ambitious story at the heart of Laura Chinn’s feature debut “Suncoast.” Based on Chinn’s own childhood experiences, the film is about a teenager named Doris (Nico Parker) with a brain cancer-riddled brother dying in the same hospice care where cultural lightning rod Terri Schiavo is also ailing. Doris just wants to experience the normal ups and downs of high school, but she has to deal with her sibling’s condition and her overbearing mother (Laura Linney). On top of that, Doris is confronted by the very questions of what death means by the protestors outside the facility calling Schiavo’s husband a murderer for wanting to end her vegetative state.

It’s a lot to capture in under two hours, and while there are some lovely beats in Chinn’s film, it’s ultimately too unfocused in the way it approaches its many themes, with one specific diversion that feels uncomfortably trite for this genuine story of growing up and loss.

Chinn, mainly a television writer who also created and starred in the short-lived TV series “Florida Girls,” sets the story in 2005 Clearwater. Brad and Jen have just broken up, Christina Milian is on the radio, and Doris is lonely.

In the opening sequence, her mother Kristine (Laura Linney) makes Doris skip riding in the van to her Christian school so she can drop her brother off at Suncoast, further isolating the already quiet girl. Doris is an afterthought to Kristine, who is largely concerned with her son’s comfort — even though that child, at this point, is barely conscious. When Kristine decides to start spending nights at the hospice, Doris takes the empty house as an opportunity to connect with her peers. She offers up her home as a party spot, ingratiating her to a new crowd, who take her in with shocking warmth. They offer her booze and drugs, but they also seem to actually want to be her friend.

The sections of the film where Doris is interacting with other kids her age are where Chinn’s work is at its strongest. Parker, who has a standout episode in “The Last of Us,” delicately captures Doris’ longing, while Chinn’s script has a knack for finding the nuances in teen talk. The other girls first use Doris’ offer to just get trashed without parental supervision, but then slowly welcome her into their coterie. They don’t fully understand what she’s going through but aren’t callous about it, either. When they misstep, it’s with the ignorance of their age, not actual malice.

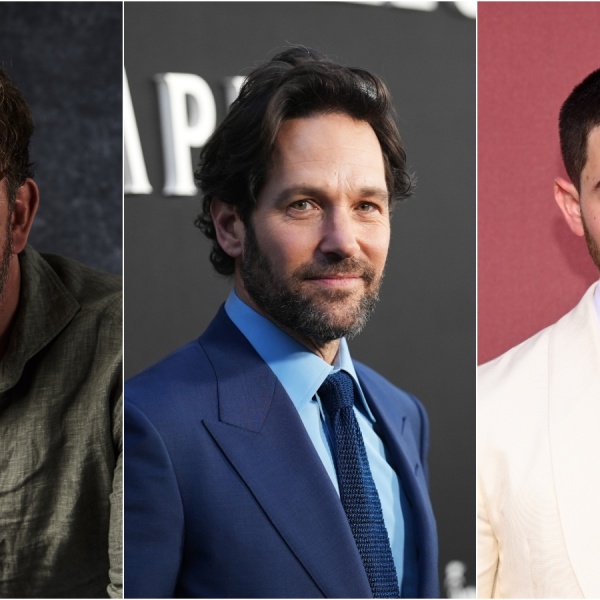

These scenes are so well-constructed that it’s a shame when Chinn swerves to the other relationship that Doris develops outside of her familial structure. While getting food at a restaurant nearby, the hospice one day, Doris meets Paul (Woody Harrelson), a widower who has been protesting the removal of Schiavo’s feeding tube. Paul is a jolly, wry, Woody Harrelson-type, who Doris takes to, craving an adult figure that isn’t her often callous mother. But their conversations are frustratingly thin, and the scenario seems like it comes from some sort of quirky indie handbook rather than something as honest as the rest of the movie.

Harrelson is doing the bare minimum as Paul, showing sides of himself we’ve seen a million times before, and Chinn’s script refuses to dig really deep into his ideology. Clearly, his activism is related to his own grief, but his political stance never really gets the time it deserves. Instead, he plays fun uncle to Doris, taking her to watch the Super Bowl and teaching her how to drive.

Every time Paul is onscreen, there’s a feeling that his storyline could be excised from the narrative without really losing much of Doris’ emotional arc. His presence takes time away from the fascinatingly tentative experience of newfound friendship with her classmates, as well as her messy connection with her mother. As with Harrelson, this isn’t a particularly unfamiliar mode for Linney, whose stridency is cut with the trauma of knowing her child is going to die. Her performance has some grace notes, including beats opposite a grief counselor at the hospice, but it feels like her and Doris’ moments together get shortchanged, making the ending feel all too rushed.

Though the roots of its tale are incredibly complicated, “Suncoast” ultimately feels a little flattened out and smoothed along the edges. Even the cinematography by Bruce Francis Cole fails to capture the Floridian dinginess implied in the dialogue, and the score from Este Haim and Christopher Stracey is pleasant but unmemorable. It’s a movie that seems all too aware that life is hard, but desperately wants to simplify it. In doing that, it does a disservice to its own ideas.

Grade: C+

“Suncoast” premiered at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival. Searchlight Pictures will release it on February 9, 2024.