In 2006, a movie came out starring Daniel Craig, Sandra Bullock, Sigourney Weaver, Jeff Daniels, Hope Davis, Isabella Rossellini, Peter Bogdanovich, Gwyneth Paltrow, and Toby Jones. That’s a murderer’s row of talent bringing to life writer/director Douglas McGrath’s script — and very few people paid it much mind. But “Infamous” was a victim of bad timing, not bad filmmaking.

One can’t blame audiences for greeting it with a collective shrug. McGrath’s movie tackled the exact same topic as the previous year’s “Capote” (the movie that earned Philip Seymour Hoffman his first and only Oscar): Truman Capote’s time spent researching and writing his true-crime classic “In Cold Blood.” After the buzzy release of “Capote” and months spent in awards season campaigning mode, no one was ready to revisit the subject.

What a shame, because “Infamous” restores much of what was missing from Bennett Miller’s much chillier take on Capote in Holcomb, Kansas.

With “Feud: Capote vs. The Swans,” Capote is once again back in the conversation (although he has rarely left it in the last 20 years). The FX limited series picks up shortly after both “Capote” and “Infamous” left off, continuing the story of Capote’s unraveling. The series pivots on the publication of Capote’s short story ”La Cote Basque, 1965,” but the seeds of his self-destruction were already in place, as posited by both feature films.

“Feud” shares more with “Infamous” than with Capote. “Infamous” luxuriates in Capote’s life with his swans Babe Paley (Weaver), Slim Keith (Davis), and Marella Agnelli (Rossellini), while also devoting time to his more prosaic friendship with Harper Lee (Bullock in her best performance). But the most startling parallel is the opening scene of “Infamous,” a deeply layered meta-commentary on storytellers.

As the camera pans across chic couples at El Morocco, singer Kitty Dean (Paltrow) takes the stage to perform Cole Porter’s “What Is This Thing Called Love?” with the band. But she’s overcome by the lyrics she’s singing, eventually stopping cold. The band falls silent and the audience stops talking, stops eating, stops doing anything but watching Kitty whisper-sing a few more heartbroken lines as her tears brim over. She recovers, snaps her fingers to summon the beat, and as the band swings back into jazzy action, she finishes the song.

Capote’s life has been encapsulated: a storyteller who becomes undone by the story. That’s the ultimate theme of all three Capote projects, though they differ on what the story was.

“Infamous” effortlessly conjures up the world Capote ruled over before systematically dismantling it. His peacocking is seductive, his conversation mesmeric. The rich and stylish are slavishly devoted to him (something we only glimpse in “Feud”). And then he arrives in Holcomb to explore for The New Yorker the effects of a quadruple homicide on a small town.

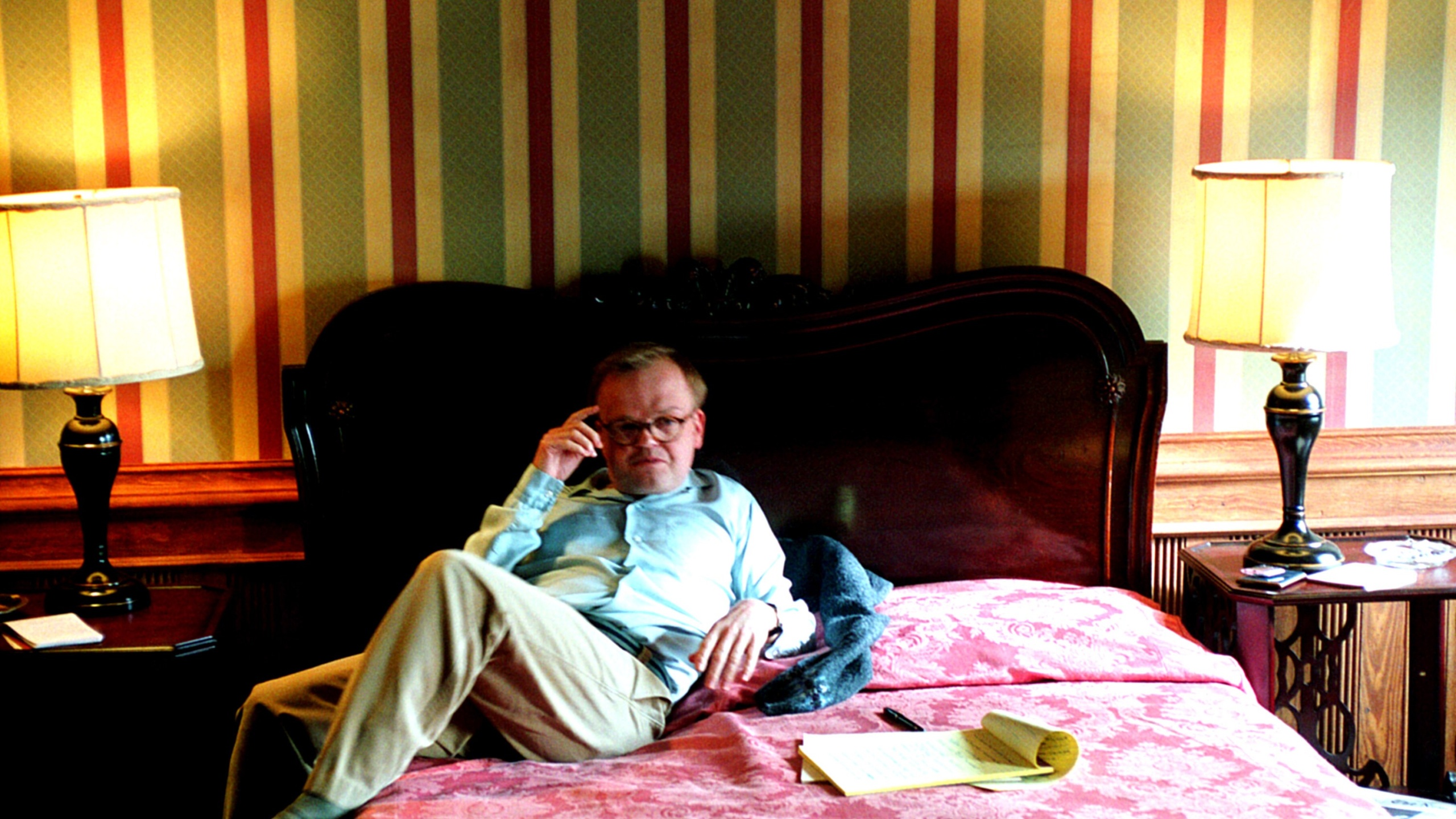

The juxtaposition of Capote’s saunter with the townsfolk whose only cheese option is Velveeta is both comic and telling. It is Lee — months away from the publication of “To Kill a Mockingbird” — who must remind him to come in on “little cat feet” as he approaches men and women reeling from the loss of their friends; his airy pretensions cut no weight with the sheriff (Daniels), though eventually his innate charm (and some old-fashioned Hollywood name-dropping) carry the day. And then Capote meets the killers, Dick (Lee Pace) and Perry (Craig), and his uncanny identification with Perry proves to be his undoing.

As “Infamous” unfolds and Capote and Perry grow closer, his superficial life in NYC begins to wear on him, even as his closeness with Perry drives a wedge between him and his partner, Jack Dunphy (played here by John Benjamin Hickey and in “Feud” by Joe Mantello). But it’s his friendships with the Swans that feel most devastating for those in the know. We see Babe tearfully confiding to Capote the very story he’ll use in “La Cote Basque” about her husband’s affair; in the very next scene, he’s discussing Bill Paley’s affair with Slim. And we see his dissatisfaction with the swans mount as they struggle to connect with his stories about something as grubby as a murderer on death row.

If the final third of “Infamous” feels disconnected from what came before, well, the same is true of Capote’s life. And though critics disparaged McGrath’s talking heads conceit, in which friends and enemies are interviewed by an unseen person about Capote (Michael Pane plays Gore Vidal for a devastatingly funny few seconds), there’s something charming about seeing these famous people play other famous people, including Juliet Stevenson as a madcap Diana Vreeland and Peter Bogdanovich as Bennett Cerf.

But if the interviews existed only to allow Bullock two monologues, they would be worth it. Her performance goes beyond acting to something approaching Patricia Neal’s unforgettable Oscar-winning turn in “Hud”: She is just existing on the screen. Whether speaking directly to the camera or conveying the comfort of an old and dear friend with Capote (their eating burgers together is a telling, far cry from his boozy, posing lunches with the Swans), her Lee is an act of near sorcery.

Embedded within “Infamous” are multiple tragedies, from Capote’s undoing to the foreshadowing of “La Cote Basque” to Dunphy’s heartbreak to the need of a double execution in order for Capote to publish his masterpiece. But it is Lee’s occasional mentions of her second book that might be the most quietly heartbreaking.

For Harper Lee, there was no second book, no second act. Sometimes the tragedy isn’t talent squandered. Sometimes, the tragedy is promise unfulfilled. “Infamous” understands the difference — and the potency — of both. Its promise was unfulfilled upon release, but do yourself a favor: Stream it wherever you can.