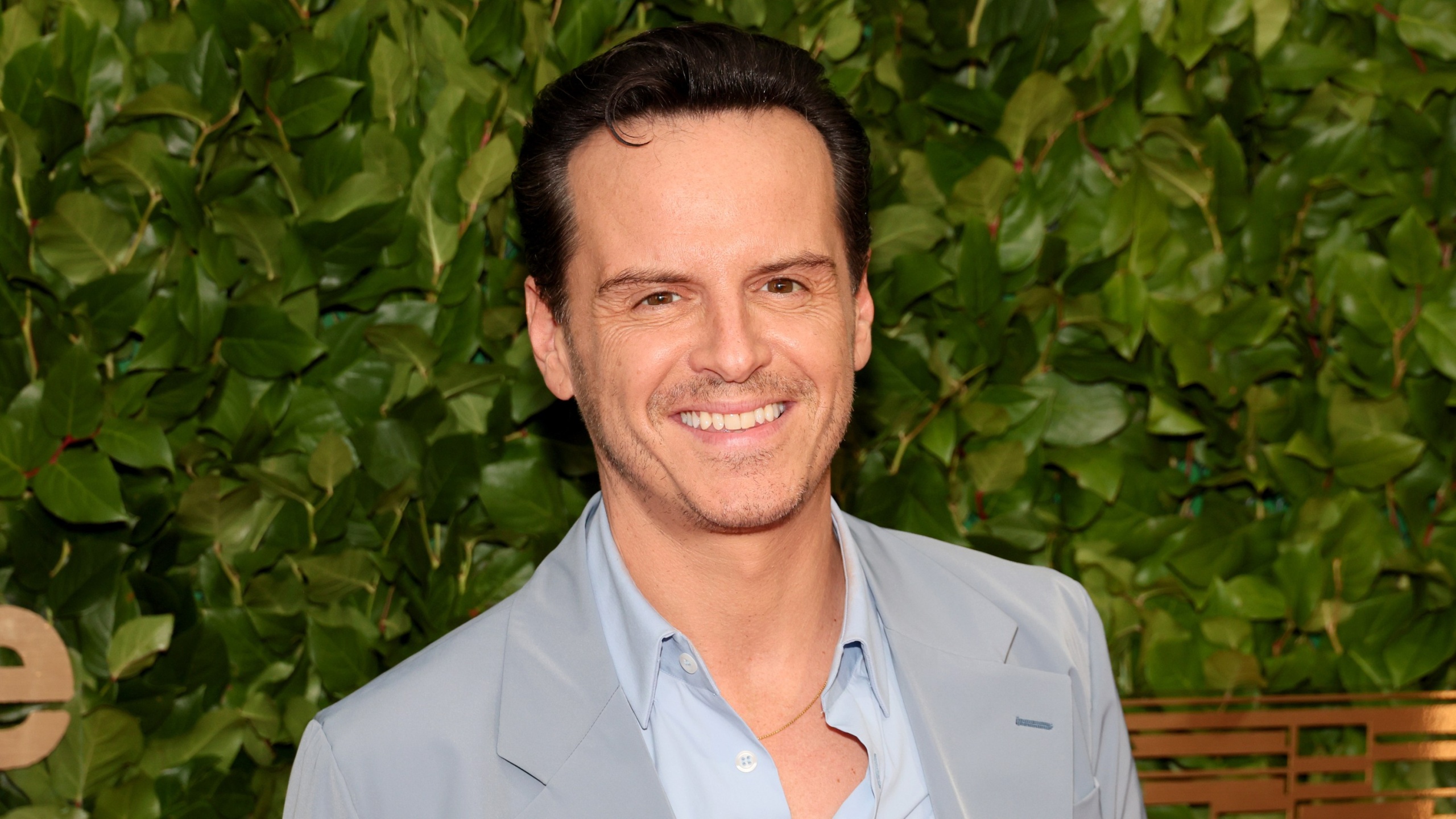

Back in 2013, Dublin-born actor Andrew Scott decided it was time to come out. He was about to do publicity for the movie “Pride.” “It got to a stage where I felt like it was an omission,” he told me recently at Los Angeles’ London Hotel. “Not speaking about it was bothering me a little. I just made the movie ‘Pride.’ And I didn’t really want to talk about that film without saying who I am. I had no shame about it anymore. So it was a brilliant thing to do. I would say to any young actor, that it was wonderful for me personally, but it was very good for my work, too. It didn’t affect my work negatively in any shape, or form. In fact, the opposite.”

He has been saying “no” throughout his career. “For me, it’s about a signature,” he said. “If the writing has a singular signature in it, then I’d be interested in doing it. It’s always the script. It’s your job, saying ‘no’ to things. I’m pretty affable as a person. But when it comes to choice-making, I don’t really care what anyone else thinks. I have quite a strong idea about what I’d like to do.” He laughed.

For example, before he played Moriarty in the BBC series “Sherlock,” he was eager to play Venom. “And then, after Moriarty comes out, ‘Oh, I don’t want to do that anymore.’ And even though you might be offered stuff that’s going to give you some good old cash and increase other things, you just have to be pretty ferocious.”

He’ll turn up for old theater friends like Sam Mendes (“Spectre” and “1917”) and Phoebe Waller-Bridge (“Fleabag”), of course. “If you don’t want to be perceived constantly with something, then you say ‘no,’ and don’t work for a little while,” Scott said. “And I’ve always I’ve done that, even when I was 19. I’m starting at the Abbey Theatre, I was offered a part that was similar. I had no cash. But I was like, ‘No, I don’t want to do that.’ And I’ve gotten used to it.”

Scott has turned down some big Hollywood roles. “They’ve come my way,” he said. “And it’s not even necessarily that you’d be selling out, but you just go, ‘I played that already.’ Do what’s of value and what’s of value to me.”

Scott’s new movie, the gay romance “All of Us Strangers,” has been whipping up audiences from Telluride to Toronto and beyond. He didn’t get to see it in a big screen (as opposed to a small screening with costar Paul Mescal) until a recent visit to Los Angeles.

That’s when he saw how the film touched a theater of 300 people. But he felt… exposed. That’s because Scott plays an adult man meeting in his childhood home the parents (Jamie Bell and Claire Foy) who died when he was 12 years old. They talk about many things. And the man is child again.

“There’s the purity of the idea that 30 years after your parents have left you that you can adopt adult things and say, ‘This is the way I am now,’” said Scott. “And that, in some ways, you might imagine that you’re invulnerable to what they might think of you. Of course, that’s not in any way true. The reason that it’s moving is that there’s nuance in it. A lot of gay people’s experience isn’t necessarily as extreme as it’s sometimes portrayed in drama, meaning that it’s not universal adoring acceptance nor is outright rejection, that actually what happens is a discomfort and an accidental cruelty from your parents, so that even if they love you, they’re going to ask you clumsy questions. They might judge you, and they might make you feel unseen, but they still are trying to understand. That’s maybe a more universal experience than we imagine, particularly as it’s represented in the cinema.”

Watching himself, “you can see the pain,” he said. “The challenge of the part was, it doesn’t take much to bring you back to where you were. Mercifully, I feel like I’m pretty comfortable with myself and have been for a long time. But I have to go back to that place where as a preteen, you can’t quite go. Just feeling like, ‘Something about me, I need to conceal.’ So how do you bring that childish vulnerability to the screen without gilding the lily too much? You feel like you want to get at that vulnerability, but you don’t want to do it in general terms. I have a good relationship with my childish self. I play for a living? (Laugh.) But still, even seeing it in the auditorium? I think ‘Wow, there’s not much skin there.’” He laughed again.

After years of leading roles in theater and supporting roles in movies and television, Scott’s role in “All of Us Strangers” is the starring lead he’s never had. It wasn’t a hunger he was itching to satiate, he said. Scott had recently taken on all eight roles in Simon Stephens and Sam Yates’ adaptation of Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya” onstage at the National Theater (“exhausting”) and during the pandemic, the isolated role of Patricia Highsmith’s charming sociopath Tom Ripley in Netflix’s upcoming eight-part series.

“I was in the middle of playing an enormous part,” he said, “Tom Ripley in the new version of ‘Talented Mr. Ripley,’ and I was in Italy, and I’d been away during the pandemic for almost a year. I was doing an enormous amount of acting, it was a genuinely enormous part. And so actually, I was looking forward to not acting for a little while. It was a tough shoot.”

And yet, when filmmaker Andrew Haigh (“45 Years”) came to him with this strange gay ghost story based on Taichi Yamada’s novel, he recognized something special. “It was like no other script that I’ve ever read,” Scott said. “How do you describe this film? It’s not like something something meets something else? That old trope. But there is something about this character, that I felt, ‘Wow, this is a huge opportunity.’ Because there’s so much that I feel I could pour in of my own experience. I felt like that I was right for it. I felt thrilled that he saw that in me or that he would consider trusting that with me. Then I spoke to him on the phone, and I liked him immediately. Andrew is an enormously likable, collaborative person. We had a great chat, and we worked it out.”

Scott is playing a lonely man in a modern high-rise who lives with a good deal of self-loathing. “He can’t love himself, because his parents were taken away from him when he was a child,” he said. “He can’t love himself as an adult person, because he doesn’t have his parents’ approval. So he may imagine what they might have thought of him. But you can only imagine. So by actualizing them, he gives himself the chance to be loved and to first of all to be seen, and then maybe to be slightly rejected, but then ultimately to be loved. And that allows him then to complete the other side of the story, which is to love rather than be loved.”

For Scott, there’s a reason this movie was so enjoyable to do. “It’s because everybody wanted to be there,” he said. “Paul Mescal was able to see something in that part, a part that he didn’t necessarily have to play. Because he’s an actor in his blood, he wants to play love, he wanted to be a vessel for, a symbol of, of love for this character. He understands the dramatic significance of that for an actor, the acting opportunities within that. That’s why he’s so mesmerizing.”

The love scenes with Mescal weren’t hard to do. “People talk about chemistry a lot,” said Scott. “And I don’t think there’s any doubt that Paul and I had chemistry. But the chemistry between the two characters is different than the chemistry Paul and I have, so that takes a lot of, ‘How would they talk to each other, who’d be feeling more confident here?’ The most intimate scenes are not necessarily the sex scenes, but the ones that are maybe pre-or-post-sex. It’s beautiful, and it’s tender. Tenderness between particularly two male characters is radical. That’s more radical than sex scenes. Because a prejudice exists where somebody’s fucking somebody but tenderness is actually the thing that is more threatening to certain factions of the community.”

As a man of the theater, Scott understands that you don’t have to explain everything to audiences, most recently in “Vanya.” “One of the liberating things about playing all eight characters, is that you don’t need to do all the stuff that you think you might need to do in a theater,” he said. “You go, ‘OK, well, I’m going to do this slight thing that’s going to denote this character,’ and the audience immediately accepts it. In the cinema, sometimes we need to CGI somebody to give a sense that it’s a ghost or there needs to be some incidental music that’s going to spell it out for us. Andrew absolutely refused to do that. It allows the audience to do some work. Where you go, ‘I’m here, and we both look like the same people, but there’s something imaginatively that’s going on.’ That’s the way our memories work: our memories don’t have CGI. It feels like as real choices as reality does.”

As close as the character is to him, Scott chose to wear his own clothes in the movie. “Andrew, we shot it in his childhood home,” he said. “He wore it so lightly. We see it as the set, but such an extraordinary amount of memories floated back for him. I kept thinking, ‘Oh, my God, when he came out to his parents, he could have gone into that little bathroom there that the crew are stomping through.’ I felt, if this character is a marriage between Andrew and me, then I wanted to bring as much of myself to the character as I possibly could. It meant not acting, not pretending to be somebody else. The clothes and my voice are just the way I am. I didn’t want to go over this character. Because the more and more I go through this job, I realize it’s about bringing as much of myself into things rather than vice versa.”

One of the things Scott realized when he came out was that “people recognize authenticity,” he said. “People like the idea of transformation, the idea of that person is authentically that. What you have to do is to be more ferocious about the work you choose to do. But I don’t think that’s exclusive to just gay actors. That’s for all actors. You have the right to say ‘no.’”

Searchlight Pictures will release “All of Us Strangers” in theaters on Friday, December 22.