“Can’t people just be humane, peace-loving citizens?,” Min-sung (Park Seo-joon) asks at the beginning of “Concrete Utopia,” wondering aloud why the hundreds of apocalypse survivors using his apartment building as makeshift shelter can’t simply share resources and work together.

It’s a lovely sentiment, but writer/director Tae-hwa Eom appears to take his protagonist’s rhetorical question as a personal attack. From there on out, he devotes every subsequent frame of his film to explaining why humans are apparently incapable of doing anything good for each other. In the film’s view, only one human institution is strong enough to stand steadfast when our innate barbarism rears its ugly head: the condo board.

“Concrete Utopia” opens with a brutal earthquake that reduces Seoul to rubble and instantly forces its surviving population to revert to a hunter-gatherer society. The film wisely wastes zero time explaining why the disaster took place, forcing audiences to adjust to the new reality as hastily as its characters. The only structure in Seoul that seems to have withstood he seismic shock is Hwang Gung Apartments, a luxury residence that remained untouched after the earthquake.

The residents can hardly believe their good fortune, but complicated moral dilemmas quickly arise as they try to figure out how much charity they can afford to offer. Their once-cosmopolitan city is now filled with newly-homeless vagabonds who will kill each other on the street for canned goods — and the only thing sparing them from the same fate is the fact that their landlord hired a slightly more competent architect than everyone else’s. The human urge to help one’s fellow man quickly crashes into the universal urge to look out for one’s own safety at all costs.

The impossible choices immediately begin to take their toll on the marriage of Min-sung and Myung-hwa (Park Bo-young). The young couple, who were building a pleasant middle class life off of civil servant salaries when the disaster struck, are quick to open their home to a single mother looking to get her toddler son out of the cold for a night. But when their new roommates don’t leave, her sense of charitable duty begins to diverge from his desire to save the occasional luxury for themselves.

They’re far from the only Hwang Gung residents dealing with unwanted dependents. As the last freestanding shelter that exists in the city, the building quickly attracts hundreds of refugees. The building’s limited resources and amenities quickly become sources of conflict among its population, and it becomes clear that some kind of formal government needs to be implemented. Enter the condo board.

For as long as human beings have lived together in large buildings that they don’t actually own, they have organized themselves into arbitrary committees that rule on the legality of festive door knockers and the financial viability of updating the snacks in communal vending machines. It was inevitable that something similar would eventually form at Hwang Gung. The building’s residents quickly establish their own set of parliamentary procedures, elect a leader, and use black and white go tiles to hold anonymous votes about questions like “should we let outsiders in?” and “should we share our food or fend for ourselves?” It offers the illusion of a civilized process, but it isn’t long before survival instincts begin luring even the most mature citizens towards violence.

It isn’t hard to see why “Concrete Utopia” was selected as South Korea’s official submission for the Best International Feature Oscar, as it bears an obvious resemblance to films like “Parasite” and “Snowpiercer,” which also used genre film tropes to mask scathing commentary on class divides. The setting of an apartment building is particularly interesting, as it’s easy to get immersed in the story before reminding yourself that these people are killing each other over the question of whose dead landlord was cooler.

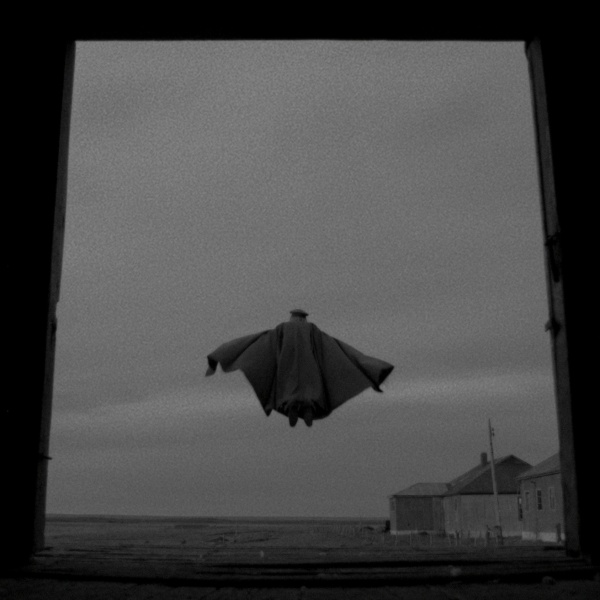

While the film lacks the originality of many of the films it tries to emulate, it’s still a solidly crafted reminder of the absurdly tragic fate that our current housing system appears to be guiding us towards. The eerily cold production design captures the emptiness of luxury in a world that no longer values it, and both Parks give performances that illustrate how delicate our sense of humanity can be in times of true crisis.

If nothing else, there’s a perverse finality to the knowledge that the Byzantine procedures that prevented you from hanging a wreath on your apartment door will live on much longer than you will.

Grade: B

815 Pictures and Seismic Releasing will release “Concrete Utopia” in select theaters on Friday, December 8 before it expands nationwide on Friday, December 15.