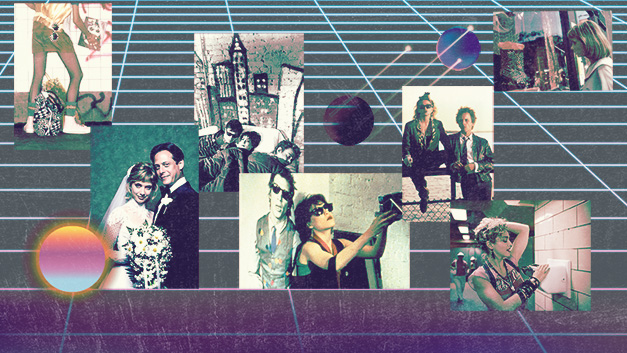

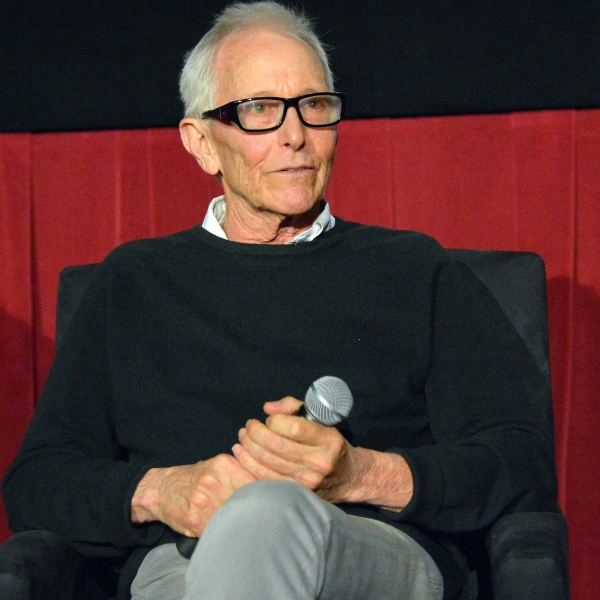

“I wanted to tell stories about people who I wanted to watch on screen,” says Susan Seidelman, the director behind a number of landmark ‘80s films that range from the fearless punk drama “Smithereens” to the Madonna-led classic “Desperately Seeking Susan.” It was never much of a mystery as to who those people were: Over the course of a career that would continue to shape American culture for the rest of the 20th century and beyond (later credits include the pilot for “Sex and the City”), Seidelman has consistently focused her sharp lens on the changing place of women in American society, and the work she made in the 1980s helped fundamentally reshape our national self-image in ways that are still being felt today.

Seidelman came to the cinema after studying fashion at Drexel University, where a film appreciation class had reawakened the fierce love for genre films that she felt as a child in the suburbs of Philadelphia. She applied to NYU film school on a whim — and was accepted.

It was an unexpected plot twist for a girl who came of age in the 1960s, when a generation of American women found themselves caught between outdated gender norms and the second wave feminist revolution. “I was brought up to be a suburban housewife,” Seidelman recalled during a recent phone interview with IndieWire, reflecting on the expectations that she would begin to challenge with some of her very first student films, such as “Yours Truly, Andrea G. Stern,” about a girl adjusting to her divorced mother’s new boyfriend, and “And You Act Like One Too,” which comically chronicles a wife’s wandering eye.

While Seidelman would later return to the “vague discontent” that plagued suburban housewives in her breakout hit “Desperately Seeking Susan,” her debut feature zeroed in on those women who pursued an alternate path. Women like Wren (Susan Berman), the heroine of her 1982 indie breakout “Smithereens,” a stylish runaway from New Jersey whose unbridled ambition is unmatched by her talent.

“The early ‘80s was an exciting time to be a New Yorker,” Seidelman said, “and a cheap time to be a New Yorker.” It was a time when a wanderer and misfit like Wren could easily move from place to place with all of her belongings in a couple of plastic bags, squatting in artist lofts, and generally eking out an existence without doing much actual work.

The first American independent film invited to compete for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, “Smithereens” takes full advantage of its location. The dawn of Koch-era New York has never looked more appealing, as Seidelman not only captures the city’s grit, but also the vibrancy of its colors. Grit and vibrancy would become defining elements of Seidelman’s cinema, as evident in her locations as they are in her heroines. In “Smithereens” and elsewhere, Seidelman uses pink — the color most often associated with femininity — in a purposefully pointed way that reflects her talent for expressing character through costumes. Wren wears a fluffy, very feminine baby pink jacket, but by the end of her journey in the film, Seidelman observed, it’s soiled and fraying, just like her unrealistic dreams of fame and fortune.

The painfully untalented Wren knows something is happening in the downtown scene, and she desperately wants a piece of the action. She plasters the subway with photocopies of her own face, a self-promotion scheme that precedes the influencer age by a couple of decades. She’s also not especially pleasant to those around her, which is kind of the point. “At the time,” Seidelman recalled, “the idea that your character had to be sympathetic was incredibly important, especially in studio meetings when they were analyzing scripts.” But she balked at the notion, wondering why no one ever asked if Dustin Hoffman was sympathetic in “The Graduate” or “Midnight Cowboy.”

“Those characters are interesting,” she said. “They’re flawed, but they also have positive characteristics, like determination and survival instincts.” For Seidelman, it was less important to create a “likable” character than it was to create a relatable character. Wren is a survivor, or as Seidelman puts it, she’s “somebody that you can kind of knock down and will get back up.”

In an era when conformity was key, Seidelman made it her mission to bring flawed but relatable female characters to the big screen. Leora Barish’ script for “Desperately Seeking Susan” had been kicking around Hollywood for so long that the title character was originally written as, what Seidelman calls “a hippie traveler.” “She was somebody who would have just gotten back from Guatemala wearing Jesus sandals or something.” Orion Pictures had envisioned a star like Diane Keaton or Goldie Hawn in the role, but when Susan came on board as director — bringing her first-hand knowledge of the downtown scene along with her — she immediately shifted the character’s background and suggested Madonna, who was then on the cusp of superstardom, for the role. The rest is history.

But “Desperately Seeking Susan” wasn’t such a revelation because it had a dynamic female lead, it was a revelation because it had two of them. In stark contrast to Madonna’s free-spirited Susan, who wears bras as tops and will trade her (now-iconic) pyramid jacket for some bejeweled boots she sees in a window, the film gives us Rosanna Arquette’s bored New Jersey housewife, Roberta. We first meet her in an old-fashioned beauty parlor where she’s getting her hair done and reading a personals ad from a musician named Jim, who is “desperately seeking” his wandering lady friend Susan. “Desperate,” Roberta gasps, “I love that word. It’s so romantic.”

Roberta is a woman who followed the path laid out for her, and for Seidelman by extension. She’s got her own home. She’s married to a man who owns his own hot tub and jacuzzi business. What could be possibly be more perfect? And yet, something is just… off.

It’s that vague discontent again. Seidelman noted that Roberta “Isn’t critical or depressed or bitchy or anything. She just knows that there’s something more out there.” She projects this fantasy on the couple she reads about in the personals, and later falls down a figurative rabbit hole, switching lives just long enough to explore an alternate path – and maybe find true love with Aidan Quinn’s soulful film projectionist, Dez.

Sedielman again uses shades of pink to juxtapose these two paths for women. Roberta’s more traditional suburban life is decked out in pastels – including an aggressively pink bedroom – and shot in soft light, whereas the more progressive Susan wears black and hot pink, while her haunts — a new wave club and a magic-themed bar — are filmed using industrial strength gels. That sharp contrast between fashionable swagger and dreamy wistfulness allows “Desperately Seeking Susan” to weaponize its screwball energy towards an insightful portrait of female friendship in the vein of Claudia Weil’s “Girlfriends,” albeit one that exchanges the realism of that earlier film for a Wonderland version of the East Village brought to life through Seidelman’s collaborations with cinematographer Edward Lachman and production designer Santo Loquasto.

Unsurprisingly, Orion’s marketing department didn’t know how to sell a film where the heterosexual romance took a backseat to female friendship and self-actualization. One rejected poster concept that feels particularly emblematic of that struggle revolved around Arquette’s image reflected in a metal toaster as a piece of toast popped up with Madonna’s face on it (in the end, they mercifully went with a minimalist design featuring a promo photograph shot by Herb Ritts). The message may have been garbled on its way to the masses, but audiences were so ready for something like this that it hardly seemed to matter, and “Desperately Seeking Susan” went on to become one of Orion’s biggest hits.

Seidelman followed that success with a pivot to another favorite genre: sci-fi. 1987’s Miami-set “Making Mr. Right” stars Ann Magnuson as Frankie Stone, a PR executive hired to “humanize” an android named Ulysses (John Malkovich) who was created for the purpose of space travel by a stoic scientist named Jeff (also Malkovich). Stone’s plan is to market Ulysses at women, making him such a star asset that Congress will continue funding the program. The high-concept premise reflects both the optimism that surrounded the space race during Seidelman’s childhood in the 1960s, as well as the troubles that NASA was experiencing by the time Seidelman’s career went stratospheric. Beyond that, the Miami setting — with its retro feel, pastel palette, and art deco hotels — offered Seidelman a refreshing new design aesthetic after making two-films back to back in Manhattan.

We’re first introduced to Frankie in crisis and pajamas as she throws all of her cheating ex’s stuff out the window, but when she arrives at work the next morning she’s dressed in a sleek yellow blazer, and hard as nails. She can be everything, all at once. “Frankie was inspired by those great actresses from the 1940s,” Seidelman said, “like Rosalind Russell, who were strong and feisty and vulnerable.” For Malkovich’s part, the director saw Ulysses as a twist on the “Pygmalion” stories that were aimed at teen boys at the time, like “Weird Science” or “Mannequin.”

Rather than have a woman created for a man’s pleasure, “Making Mr. Right” flips the mythology around while also exploring the contemporary politics between men and women and the prominent macho culture. As Frankie teaches Ulysses — and Jeff — about the importance of emotions, companionship, and platonic intimacy, Seidelman slowly chips away at a kind of male repression that is a symptom of what we’d now call toxic masculinity, all while finding new strength in aspects of humanity often dismissed as feminine. It’s a triumph over the false gendering of open-heartedness and vulnerability.

Seidelman finished the ’80s with two films in quick succession, though not on purpose. “Cookie,” starring Peter Falk, Dianne Wiest, and Emily Lloyd, completed filming in early 1988, but its release was delayed due to issues with its production company Lorimar. The film was then sold to Warner Bros. for distribution, where it became as Seidelman described, “an orphan project.”

Penned by Alice Arlen and Nora Ephron, the comedic father-daughter twist on the mafia movie seemed fresh while the film was in production, but by the time of its release it felt stale coming after a hit like Jonathan Demme’s “Married To The Mob.” Of the film’s ill-fated delayed release, Seidelman mused that “one of the things that I’ve come to realize over the course of three decades is that timing is so important. You need to have a good film, but a good film and bad timing doesn’t work.”

This truism can also apply to a film like Seidelman’s follow-up, “She-Devil,” which in many ways still feels ahead of its time, and which Seidelman herself called “probably the most feminist” of her movies. A riff on the beauty myth and a critique of how society pits women against each other for the sake of men, the film stars Meryl Streep as Mary Fisher, a narcissistic romance writer, and Rosanne Barr as Ruth, a harried housewife and mother of two, whose lives intersect when Ruth’s accountant husband Bob (Ed Begley Jr.) strikes up an affair with Mary.

Based on Fay Weldon’s novel “The Life and Loves of a She-Devil,” the comedy once again finds Seidelman making full use of her favorite color, as pink suffuses the lives of the film’s leading women. It’s all part of the director’s ongoing efforts to explore the trappings of beauty standards and the dismissal of traditional “women’s work,” like childrearing and household management. “We are a culture where there’s rules about what is beautiful, and especially for women,” Seidelman shared. “Ruth is a victim of the beauty myth because she doesn’t fit the bill.” But so is Mary, whom Seidelman described as “hyper-feminine,” and whose entire world amounts to a pink gilded cage that less resembles a typical home than it does Barbie’s Dream House Mansion. Mary’s world, Seidelman said, was always meant to be a fairytale illusion.

Both these women curb their behaviors to please the men in their life, whether it’s Mary’s fantasies about being the perfect romantic doll, or Ruth’s attempt to be the perfect housewife and mother. Both of them eventually go through powerful journeys of self-actualization, with Ruth using her household management skills to create a business that helps uplift other women, and Mary adopting a darker wardrobe and tackling “serious” fiction.

Naturally, the film’s marketing focused on the pitting the two female characters against each other. One poster finds a deranged Rosanne choking a poised Mary below a tagline that reads “Revenge is sweet… and low.” An alternate sees Begley kissing Streep on the cheek, as Barr hovers behind them in a swell of flames. The tagline reads: “The story of the greatest evil ever known to man… His ex-wife.”

Both posters somehow broadcast what Seidelman described as the “reverse of the theme of the movie,” which likely scared off the audiences that would have enjoyed “She-Devil.” The era’s male-dominated film culture didn’t help. “Most critics saw it as male-hating,” Seidelman recalled, when really the film was a satirical social commentary of the boxes women found themselves in. It would seem the director saw that coming to a certain degree, as Mary — in a scene where she’s promoting her latest, less women-centric book — makes note of the fact that her work is finally getting good reviews from “serious” critics, while slyly flipping off the camera as she adjusts her pink glasses. “She-Devil” flopped so “Barbie” could soar.

Thankfully, in the last decade or so the film has found a new life and a new generation of fans, and Seidelman is delighted by the evidence she sees on Instagram of “a younger audience, and jot just women, embracing the film in a different light than the audience 30 years ago.” She partly attributed the reassessment of “She-Devil,” along with the growing reverence for the rest of her work, to the fact that more women are writing about movies today than they did when she was first starting out.

Seidelman told stories about the types of people who she wanted to watch on screen, and now — thanks to her efforts — she can see them reflected back at her everywhere she looks.

Susan Seidelman’s films are currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.