Editor’s Note: This review was originally published at the 2023 Venice Film Festival. Briarcliff Entertainment will release “Dogman” in select theaters on Friday, March 15 before expanding on March 22.

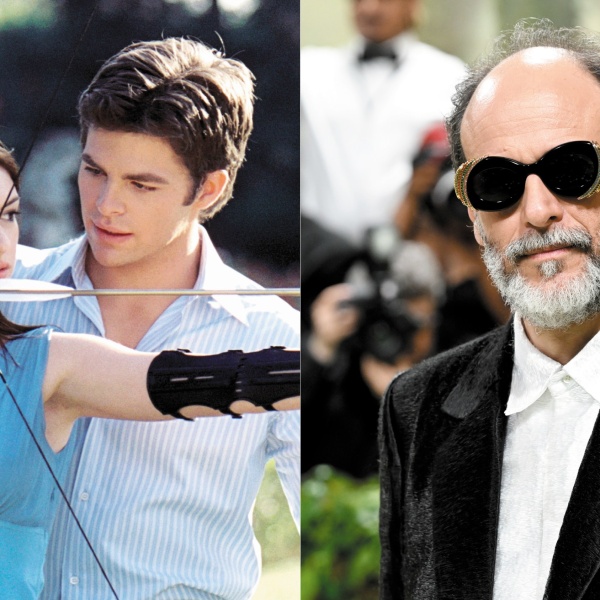

Caleb Landry Jones graduates from menacing oddball character actor to sympathetic show-stopping lead in Luc Besson’s “Dogman.” But the French genre filmmaker’s first feature effort since 2019 assassin thriller “Anna” — and his second since 2017’s catastrophic space opera “Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets” — unfortunately doesn’t deliver the goods to match Landry Jones’ giddily unrestrained turn as a traumatized dog collector turned drag cabaret act turned … well-heeled shooter and avenger of capitalist greed and domestic abuse?

That’s nothing against the 33-year-old American actor’s Method-level dedication to the role (to note, the actor showed up to the “Dogman” Venice Film Festival press conference fully in a Scottish accent to prepare for a future performance). Landry Jones has stamped himself as indie film’s consummate weirdo, playing charmingly raffish outsiders (“Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri”) or scary psychos (“Twin Peaks: The Return,” “Nitram”). His Douglas in “Dogman” is a little bit of both, but it grows disconcerting how Besson connects terrible formative abuse to a later queer identity.

We first meet Douglas Munrow (Landry Jones) in a strapless dress, mussy blonde wig, and Edith Piaf extremes of garish white face makeup, bleeding out from the back and getting arrested from the driver’s seat of a car. He’s been brought in for questioning not only about his disarrayed condition but also potentially for a string of killings and seemingly unrelated home invasions. He’s bound to a wheelchair, and being questioned by psychiatrist Evelyn (Jojo T. Gibbs), with whom he forms a simpatico bond over similar past and present traumas. (Evelyn is a character who’s not doing well at home, either, and whom Besson halfheartedly fleshes out.)

So from this prison interrogation room, “Dogman” unfolds as a frame story revealing decades’ worth of flashbacks, starting with Douglas’ ugly New Jersey childhood, beaten by his father, who was a cruel dogfighter. There are echoes of Arthur Fleck (beyond just his streaming, caught-in-a-gutter makeup) and even Norman Bates in Douglas’ disaffected recounting of terrible events — but he’s no sociopath and actually a bit of a broken-hearted sweetie. Besson based his English-language screenplay on an article he read about a French family that locked their child in a cage at the age of five, and the “Léon: The Professional” director spent a year with Landry Jones in preparation for what is visibly a soul- and body-consuming role. But the central core of “Dogman” — Landry Jones as a grown-up survivor of childhood brutality who tries to forge an empowered identity beyond it — gets lost in Besson’s tendency to overstate through combat, gore, and over-the-top, heist-y genre business.

We learn that the only affection Douglas received as a child, and seems to still get as an adult, came from dogs. Douglas’ love for canine creatures is one he cultivated as an abused kid sneaking food scraps to the ravenous dogs his monster of a dad, Mike (Clemens Schick), left to starve, keeping them on edge for prime fighting. Eventually, Mike locks Douglas in those cages, too — and his pregnant mother flees the scene to give her next child a hopefully better life than the current one. Douglas gets out, raising himself on plenty of other female influences, including the Modern Woman magazines found behind the walls of his childhood cage. Now, in present day, he lives in an abandoned, squalid high school building in a hellish corner of town, taking care of dozens of dogs he’s collected from shuttered refuges, and whom he now calls his “children.” And the show dogs, surely the most well-trained you’re likely to see onscreen in a long time, end up the stars of the picture. (And just if you were wondering, no, no dogs are killed in this movie, though plenty of human blood and viscera are shed.)

But Douglas’ brood of pets’ greatest flaw is their trustworthiness toward humans, which gets him into trouble with a pack of vaguely stereotyped and vaguely drawn Latino gangsters. Plus, there’s a nervy private detective who gleans from a moneyed New Jersey housewife that Douglas has been dispatching his “babies” to go all “Bling Ring” on the super-rich, stealing their diamonds and other jewels in the middle of the night without so much as a paw print or errant hair left behind. It’s rather astounding what Besson and Mathilde de Cagny, who’s worked as a lead animal trainer on films including “Beginners” and “Marley & Me,” achieve here, and outside of Landry Jones’ performance, it’s the main thing “Dogman” has going for it.

Equally heart-tugging is Douglas’ rise from a youngster theater wannabe into drag culture, performing as high priestess of pain Piaf onstage in a dismal New Jersey club despite injuries sustained from a ricocheting bullet as a caged child. Douglas lives in leg braces that prevent him from standing or even walking too long, and Landry Jones imbues stage-set scenes of Douglas’ performances — once as Piaf and another as a rather dashing Marlene Dietrich before he goes full Marilyn Monroe during a climactic shootout spree with his enemies — with a convincingly look-at-me-triumph, daddy-watch-me-twirl edge. Still, “Dogman” isn’t quite sure what it’s trying to say with regard to gender expression and the fluidity of Douglas’ identity, even if Landry Jones may be. We know from a crush Douglas had on a former juvenile care worker — a system he was thrust into after surviving familial abuse — that he’s probably heterosexual-leaning. But there are no labels, and Douglas’ romantic or sexual life isn’t one Besson is keen to explore. There’s something just a hair troubling here about how “Dogman” seems to draw a tenuous line from abuse to eventual adulthood queerness.

Despite its queer-adjacent aspirations that suggest a more subversive offering, the movie devolves into a pile-up of action-heavy machismo carnage, with Besson unable to resist a cheesily staged blow-em-up in Douglas’ hovel of a home, facing off against gangsters that want his loot. Booby traps abound, and “Dogman” winds up rather silly for them, a kind of comical “Home Alone”-esque final blowout that’s only satisfying in how the dogs end up winning the day. It feels like in the movie’s last collapse, Besson forgets the beautiful soul he’s created until then — even if in revealing the stockpile of shotguns Douglas keeps in a closet “Dogman” tries to elucidate a wounded soul taking control. While this film probably needed more time in the storytelling doghouse, Landry Jones’ performance is a lovely watch.

Grade: C

“Dogman” world premiered at the Venice Film Festival. It is currently seeking U.S. distribution.