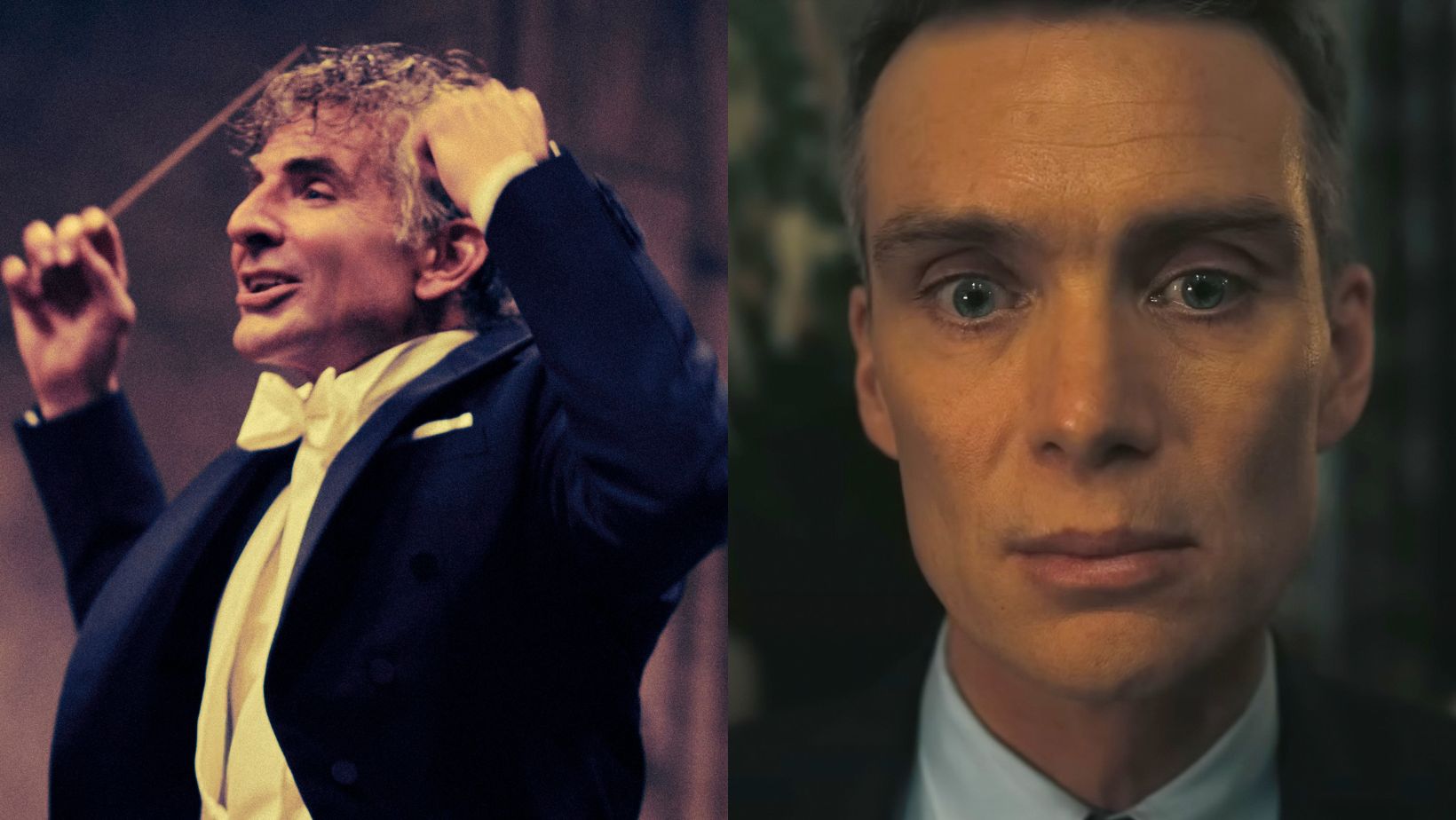

It’s not often that you get two films in the same year devoted to a couple of Twentieth-Century giants of science and music as “Oppenheimer” and “Maestro.” But then theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) and conductor-composer Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper) were both legends deserving of lofty cinematic treatment, and directors Christopher Nolan and Cooper delivered dazzling spectacles of sight and sound. Which is why these Best Picture contenders will likely also be craft juggernauts for Universal and Netflix.

Interestingly, both movies were not only shot on Kodak film (15 perf/65mm IMAX for “Oppenheimer,” 35mm for “Maestro“), but also in color and black-and-white. This was to distinguish the timelines and to heighten the emotional toll of their titanic achievements. Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, was driven to build it and then tormented by its destruction to the detriment of his marriage to biologist-botanist Kitty (Emily Blunt). By contrast, Bernstein, the Renaissance Man of American Music, embraced his professional and personal contradictions, to the detriment of his marriage to actress wife Felicia (Carey Mulligan).

“Oppenheimer” is the more ambitious spectacle encompassing four genres — a psychological thriller, a Western, a heist film, and a courtroom drama — and brought audiences to theaters in droves ($950.5 million worldwide). This was especially true in IMAX, where Nolan and DP Hoyte van Hoytema (winner of the NYFCC cinematography award) created a new kind of intimate spectacle by exploring the landscape of faces with the large-format IMAX camera (the first time in black-and-white). To streamline an immense amount of scientific exposition and accommodate 73 speaking parts, Nolan split the narrative into two timelines and subjective points of view: Oppenheimer’s mission to build the atomic bomb at Los Alamos (in color) and Admiral Lewis Strauss’ (Robert Downey Jr.) adversarial mission to facilitate further nuclear development during the Cold War (in black-and-white).

With “Maestro,” Cooper also eschews a conventional biopic approach to focus on the bittersweet love story between Lenny and Felicia over four decades, complicated by his all-encompassing musical universe and hedonistic double life with same-sex lovers. The first half (in black-and-white) establishes the strong emotional connection between the couple as their careers begin to take off. As they drift apart, the rhythm slows down and the tension builds. The film turns melancholy when Lenny returns to Felicia to care for her when she’s stricken with cancer.

In terms of the craft races, “Oppenheimer” should grab nominations for everything, with the exception of original song (where it’s not qualifying). “Maestro” should be close behind, skipping out on visual effects (not applicable), original score, and original song (non-qualifiers).

Meanwhile, “Oppenheimer” is the favorite for VFX. In typical Nolan fashion, it relies on old-school in-camera effects instead of cutting-edge CG. Oscar-winning production VFX supervisor Andrew Jackson (“Tenet”) and Oscar-winning SFX supervisor Scott Fisher (“Tenet,” ‘Interstellar”) shot lab experiments in tanks for the simulated liquids and other materials for the quantum physics sequences. Everything was shot in camera (including 65mm IMAX) for the simulated liquids and other materials for the quantum physics sequences, and then manipulated, layered, and composited in the computer. Likewise, the Trinity atomic blast was a series of large and small practical explosions treated and composited in a grander fashion.

In addition, “Oppenheimer” is a strong contender for Ludwig Göransson’s original score. The “Black Panther” Oscar winner powers Oppenheimer’s journey with solo violin (performed by his accomplished musician wife, Serena), particularly to evoke his troubled state of mind. By contrast, he uses the harp to evoke Strauss’ Salieri-like antagonist. One of his greatest challenges, however, was composing suites for their two humiliating courtroom dramas: Oppenheimer’s security clearance hearing and Strauss’ Senate confirmation hearing.

Here’s a closer look at the head-to-head craft races:

Cinematography

“Oppenheimer” cinematographer van Hoytema (nominated for “Dunkirk”) is the favorite for achieving a new level of immersion and intimacy by redefining portraits and close-ups for 70mm IMAX presentation. (A shout out to Kodak for engineering first-time 65mm monochromatic film for IMAX in collaboration with Panavision, IMAX, and FotoKem.) Overall, it’s an aesthetic that combines naturalism and impressionism. The former encompasses the early lab experiments, the vast Los Alamos landscape, the inner workings of the Manhattan Project, the Trinity bomb blast, and the claustrophobia of Oppenheimer’s hearing and more doc-like approach to Strauss’ hearing. The latter features Oppenheimer’s inner thoughts about atomic and sub-atomic worlds and the horrific sense of guilt about death and destruction that permeate moments at Los Alamos and his hearing.

Two-time Oscar nominee Matthew Libatique (“A Star Is Born,” “Black Swan”) is back for Cooper’s sophomore film, treating it like two movies in one: monochromatic and color. Both, though, are shot in the 1.33 aspect ratio because Cooper liked the narrower horizontal framing. This enhanced the intimacy of the first half, where, for example, Lenny helps Felicia run through a scene from the play that she’s understudying at the Cherry Lane Theater, and the claustrophobia of the second half, which culminates with the remarkable, single-take, Thanksgiving fight at their Dakota apartment. But then there’s the powerful epiphany of Bernstein conducting Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 (“Resurrection”) in London’s Ely Cathedral, which serves as a microcosm of the entire film in rekindling the romantic spark between the couple for a brief moment.

Production Design

Although “Barbie” and “Poor Things” are the frontrunners for their wildly imaginative world-building, “Oppenheimer” and “Maestro” offer remarkable historical recreations. “Oppenheimer” required production designer Ruth De Jong (“Nope”) to combine sets with practical locations to build the desert town of Los Alamos from scratch at Ghost Ranch, a 21,000-acre retreat in Northern New Mexico overlooking the same mountain range as the real Los Alamos, which was too modernized to use. This provided the right plateau to build the town, with impressive backdrops in every direction. Even more challenging, though, was having to reconstruct the Oval Office in only five weeks when a location shoot fell through. For this, they pulled out the Oval Office set from “Veep,” and got it in working condition with the help of SFX supervisor Fisher’s team.

For “Maestro,” production designer Kevin Thompson recreated New York from the ’40s to the ’80s (again, in color and monochrome). The highlights include the Bernstein home in Connecticut — their actual house, which was made period accurate — and their Dakota apartment on the Upper West Side, which Thompson recreated on a stage based on the dimensions of the original.

Costume Design

While the fantastical “Barbie” and “Poor Things” are the top frontrunners here as well, Oscar-winner Mark Bridges (“Phantom Thread,” “The Artist”) and Ellen Mirojnick (the Emmy-winning “Behind the Candelabra”) are in strong contention. Bridges applied “forensic costume design” to accurately depict what Bernstein wore throughout the decades when there was a dearth of photographic evidence (such as the shawl-collared velvet dinner jacket with tuxedo pants to the opening of “Mass”). Bridges also leaned on his experience with “The Artist” to adjust for black-and-white through an understanding of how prints or textures read. Indeed, the shift to color also hinges on his costume design with Felicia’s turquoise sheath dress, which is telegraphed by the monochromatic silhouette.

Mirojnick had the enormous task of dressing 73 speaking parts and many more background actors primarily in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s. But her primary focus was capturing Oppenheimer’s iconic look and silhouette with his gray fedora and pipe: He had a preference for blue or gray suits, blue shirts, and neutral ties to show off his striking blue eyes. By contrast, Strauss was a dapper dresser (he wears a pale yellow tie for his Senate confirmation hearing rendered in black-and-white), and it was a pleasure for Mirojnick to reunite with Downey once again after helping him become Charlie Chaplin in “Chaplin.”

Makeup and Hairstyling

Oscar-winning prosthetic makeup guru Kazu Hiro (“Bombshell” and “Darkest Hour”) is the favorite for transforming Cooper into Bernstein in “Maestro” (the prosthetic nose flap was much ado about nothing). This was his greatest achievement because of the difficulty of aging Bernstein throughout five decades and because this was such a personal project — he was fascinated by Bernstein’s face as a young man and vowed to sculpt him someday. Cooper provided the opportunity. The work involved five stages (both in color and black-and-white) and took up to six hours of prep, depending on the stage. Hiro, who collaborated with Oscar-nominated makeup head Sian Grigg (“The Revenant”) and Oscar-nominated hair head Kay Georgiou (“Joker”), had the hardest time keeping the prosthetic makeup together and consistent during the “Resurrection” Symphony scene at Ely Cathedral, when Cooper was at his most energetic.

“Oppenheimer” is a three-hour film about faces, and head of makeup Luisa Abel and hair lead Jaime Leigh McIntosh had many characters to work on. While Murphy’s Oppenheimer posed aging challenges, Downey’s Strauss looks quite distinguished aged up with white hair and makeup embellishment. In addition, there’s a strong prosthetic component when Oppenheimer imagines the impact of the radiation fallout on the faces of his Manhattan Project colleagues during the celebratory gym scene.

Editing

“Oppenheimer” and “Maestro” are the leading frontrunners for their editorial daring. Editor Jennifer Lame was tasked with tackling the non-linear, cross-cutting “Oppenheimer” narrative in both color and black-and-white, shifting between Oppenheimer and Strauss’s perspectives (“Fission” and “Fusion”). Their rise and fall have their own rhythm and pace, with their traumatic hearings serving as the key framing device. But where Lame brilliantly excels is managing the tension of people talking in rooms, which dominates the film. However, what most fascinated the editor was following the emotional connection to Oppenheimer in every moment. For Lame, the turning point was Oppenheimer’s meeting with General Groves (Matt Damon) and the arc of their relationship that encompasses The Manhattan Project and its aftermath.

Emmy-winning editor Michelle Tesoro (“The Queen’s Gambit”) was tasked with tackling the bittersweet love story between Lenny and Felicia, which served as her North Star. The black-and-white first half functions as an idealized ’40s romcom, in which the transitions were done smoothly in the final cut as either straight cuts or dissolves. This is in sharp contrast to the “harsh reality” of the colorful second half. The editor said it was like “The Wizard of Oz” in reverse. As they drift apart, the couple’s tenuous emotional connection gets lost in Lenny’s enormous musical universe, where Felicia no longer fits in. Most important, though, was cutting to Bernstein’s music (recorded live for scenes conducting or composing, or re-recorded for musical cues from “On the Waterfront,” “West Side Story,” and “Candide,” among others).

Sound

“Oppenheimer” is the favorite here for its explosive soundscape, but “Maestro” is noteworthy for its innovative live recording of music and mixing for the ultimate Atmos experience. Interestingly, multiple Oscar-winning sound designer/supervising sound editor Richard King worked on both films.

For “Oppenheimer,” King and his Oscar-winning team (music and sound effects mixer Kevin O’Connell and dialogue mixer Gary Rizzo) created the horrifying sound of the Trinity test explosion along with the sounds of the subatomic world of particles and waves that stirred Oppenheimer’s troubled mind. For the former, they recreated first-hand descriptions of the blast to which they added the strange sound of “cosmic door slamming.” For the latter, they used a variety of real-world sounds, such as large, arcing sparks, physical bangs and snaps, and lots of electronic components coupled with out of phasing for light dancing waves of energy.

The sound of “Maestro” — referred to as a long symphony by Cooper — was created in a very realistic, musical way as a metaphor for Bernstein’s rapid rise to superstardom. King worked with the “A Star Is Born” Oscar-nominated team of production sound mixer Steve Morrow, re-recording mixers Tom Ozanich and Dean Zupancic, and music editor Jason Ruder. Each scene has its own specific sound and flows into the next without a noticeable transition. This included the various parties, which were miked in such a way that the actors weren’t encumbered and could shout as loud as they wanted. Yet the musical highlight was the “Resurrection” Symphony scene at Ely Cathedral, which was miked throughout the actual cathedral where Bernstein conducted the Mahler in 1973. Additionally, King was asked by Cooper to craft the sound of wind as a motif, intended to capture the wind of Bernstein’s rapid trajectory as an artist.