In keeping with Christopher Nolan‘s preference for shooting in-camera practical effects whenever possible — and a desire to steer clear of CGI on “Oppenheimer” — the director created his own real-life VFX Manhattan Project to create the subatomic world and Trinity atomic blast. That’s why VFX supervisor Andrew Jackson (“Tenet,” “Dunkirk”) was the first crew member Nolan asked to read his script.

“He needed me to get on board really early to start investigating what we could do,” Jackson told IndieWire. “And in that first discussion, we looked at the options. At one end of the spectrum, there’s trying to reproduce the subatomic electrons orbiting a nucleus and an atom spinning at trillions of times a second because the film is so much about trying to experience the story through the mind of Oppenheimer [Cillian Murphy], and we were trying to visualize what might be going on in his head at a time when there weren’t really good images of all these things.

“So an accurate representation would be meaningless. And then at the other end of the spectrum is some sort of infographic representation that the audience can understand. So we landed somewhere in the middle with an artistic interpretation of ideas inspired by the script and the thought processes in his mind.”

After reading the script, Jackson compiled a montage of tests he filmed throughout his career and screened them for Nolan to start ideating with some basic ideas. Then he spent the first two months of pre-production working with special effects supervisor Scott Fisher (“Tenet,” “Dunkirk,” “Interstellar,” “The Dark Knight Rises,” “Inception”) and his team, shooting an extensive library of microscopic particle elements on iPhones and digital cameras, from smashing ping-pong balls together to throwing paint against a wall and concocting luminous magnesium solutions and other liquids. Then Nolan would take a look and let them know what interested him.

This developed into more elaborate experiments with a small VFX unit that worked alongside the main unit. They shot assorted objects in cloud tanks with 65mm IMAX cameras (assisted by cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema) at different shutter speeds and frame rates. These included spinning beads on long wires, aluminum flakes, pieces of wood, and burning thermites. However, to reach inside the tanks, the IMAX cameras required special wide-angle probe lenses developed by Panavision senior vice president Dan Sasaki.

These experiments formed the basis of Oppenheimer’s subatomic visions of electrons and atoms or light waves and particles interacting and combining. He also had more astronomical visions about the cosmos, in which black holes were formed by imploding stars.

“And, in the end, we had this enormous library of material,” Jackson said. “Some of it applied directly to specific lines in the script and didn’t need any work in post. It could just be cut straight in. Then other things needed to combine multiple layers to be treated and manipulated [in the computer].”

These particle simulations were also applied to Oppenheimer’s darkest fears that the atomic bomb would cause a chain reaction that destroyed the planet. “We filmed real missiles and little miniature ones for the trails coming through the clouds and slowed them down and scaled them so they felt bigger,” said Jackson. “For the impact on the sky, we shot cloudscapes from helicopter aerial shots in Zurich. The clouds catching fire was just another one of the elements that we shot. But, for the earth on fire, we shot burning edges to incorporate those wider shots of the whole planet catching fire.”

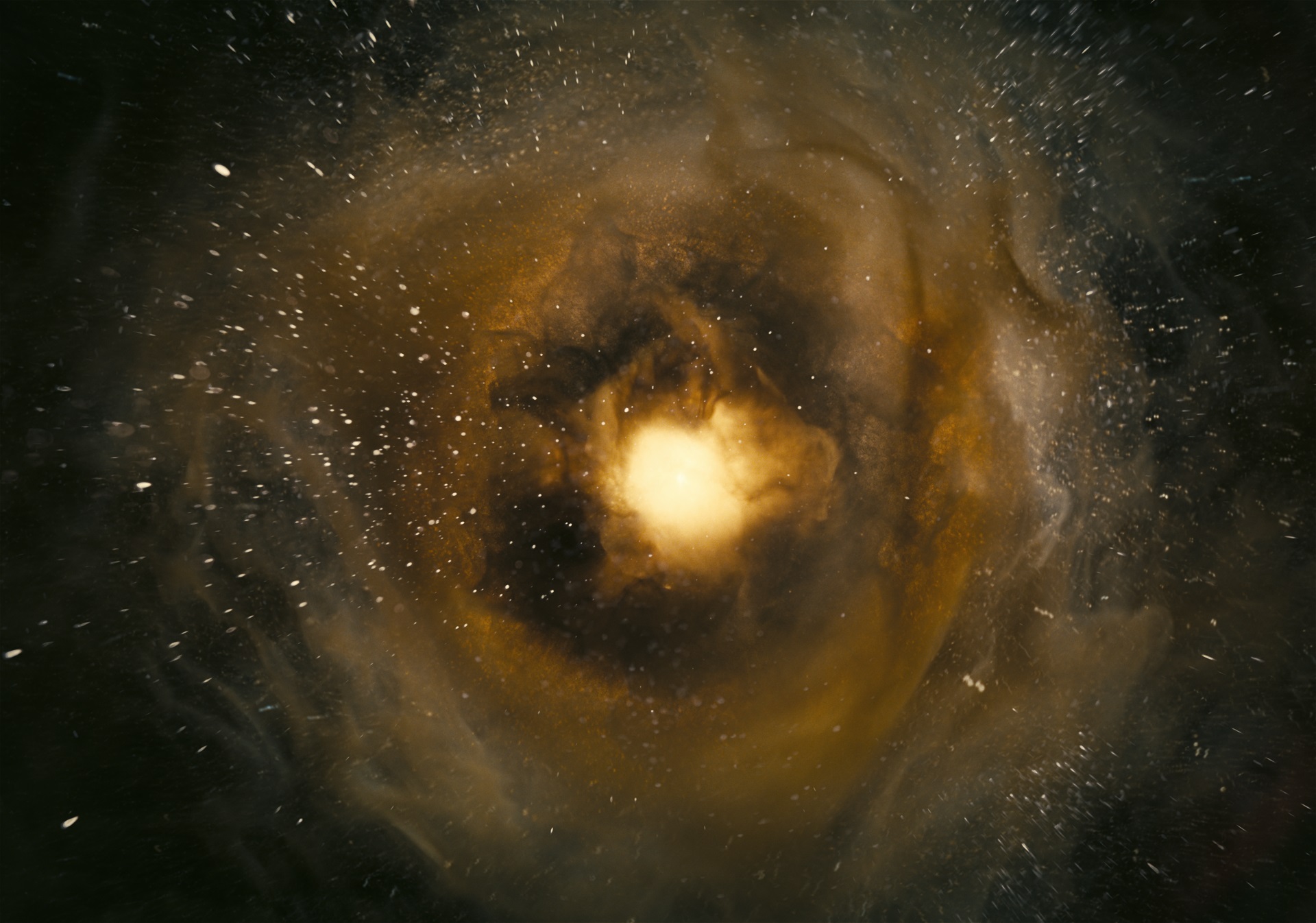

For the Trinity atomic bomb blast, Fisher’s effects department created large and small explosions with gasoline, propane, and magnesium and aluminum powder to create the flash and overwhelming brightness.

“That big volume of burning fuel tends to make itself into a mushroom shape,” Jackson added. “We placed it between the practical tower that was built and the camera so that it was scaled by bringing it closer to the camera.” They were shot at 48 frames-per-second with 65mm IMAX and Panavision Panaflex System 65 Studio cameras, while detailed sections were additionally shot at 50 frames-per-second with 35mm cameras.

Overall, there were 200 VFX shots in the film that wee stitched together through complex compositing of more than 400 practical elements from a team of 150-plus DNEG artists. “We shot them from different distances and then, in post, we took all of those elements and slowed them down even more so that they appeared much bigger than they were,” said Jackson, “and then layered them over the top of each other, so that we could build a bigger event outta the smaller pieces.”