Kohn’s Corner is a weekly column about the challenges and opportunities of sustaining American film culture.

As actors continued to strike this week, the biggest stories about performers were unrelated to the unions. First came 21-year-old YouTube and Twitch streamer Kai Cenat being charged with inciting a riot after his impromptu Union Square giveaway led thousands to storm the park. Then came the shocking announcement that 10-year-old internet rapper Lil Tay had died under mysterious circumstances, followed by the revelation a few hours later that Lil Tay was actually alive and well but the victim of a hack.

Welcome to the wild, wild west of the online creator economy that drives so much of popular culture. While SAG-AFTRA and the WGA want streaming-dominated Hollywood to provide a better support system, the internet has no infrastructure to strike against. A few weeks ago, I wrote about how documentarians have no union, although some can get into the WGA or DGA; YouTubers and their ilk don’t have that option.

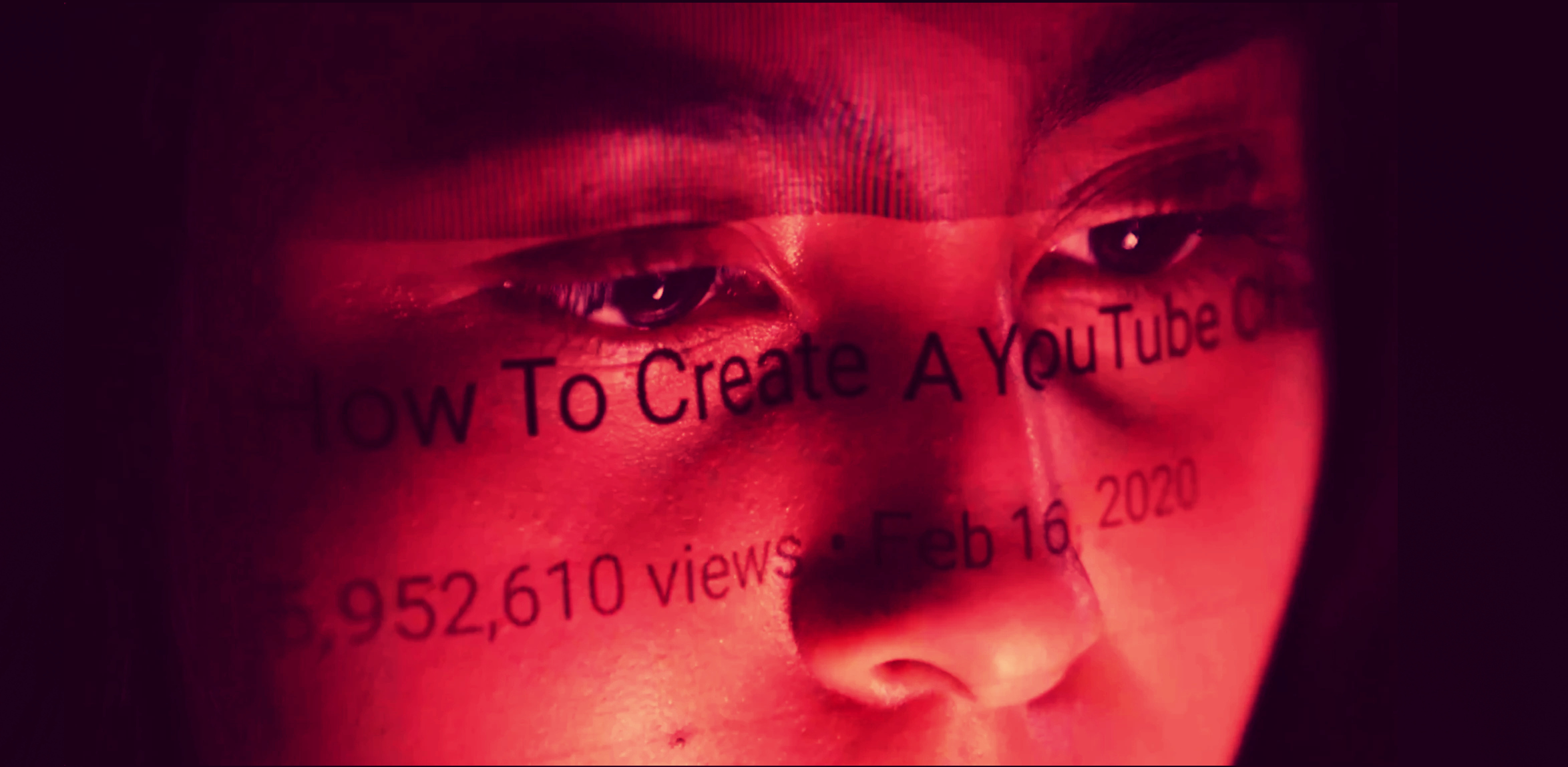

It was a good moment to catch up with “The YouTube Effect,” the latest documentary from Alex Winter. As an actor, Winter most recently recreated his most memorable role as Bill in 2022’s “Bill & Ted Face the Music” (the third in the franchise and an underrated gem), but today he’s best known as a prolific documentarian invested in the riskiest aspects of the online era.

Winter’s documentaries aren’t built around advanced filmmaking trickery. He offers laser-focused warnings about the rapid changes of a digitally centered society. From his Napster portrait “Downloaded” to “Deep Web: The Unfold Story of Bitcoin and the Silk Road,” his work chronicles the disruptive potential of technology and why so few people have the power to change it. (He also directed 2015’s “Smosh: The Movie,” a feature-length adaptation of a popular YouTube channel.)

“The YouTube Effect” follows the rise of the video-sharing platform in 2005 and its sale to Google the next year, catalyzing a whole economy of content creators. It also tackles the rise of right-wing extremism and conspiracy theories as a direct outgrowth of YouTube’s viewer-focused model.

Winter is on strike as an actor and writer, but we spoke this week as he took a break from the picket lines to discuss rhe streaming economy — a central issue of the strikes — the role of YouTube, and what’s left to be done about it.

IndieWire: How big of a gap do you see between the creator economy that YouTube created and the traditional Hollywood system for supporting talent?

ALEX WINTER: I had a production company in New York in the early 2000s mostly focused on commercials. I hired these guys to work for me out of high school who were making movies and trying to break out. They were really industrious without any money. I told them to go into the internet because that’s where things seemed to be. They became the Fine brothers [Benny and Rafi Fine of REACT Media], who just sold their six-story building in Burbank and fucking retired at 35. I’m still slaving away doing the same thing I was doing when they worked for me.

This was one of the reasons I did “Smosh: The Movie” a few years ago. I watched the Smosh guys navigating the industry as kids, kind of the way me and Tom Stern did when we got out of NYU, but there was no internet. We ended up doing our show for MTV [“The Idiot Box”] and there was literally no money in it. We were always poor. But I watched these kids monetize and build really robust careers, buying houses and starting families. That’s not for everyone, but it’s been fascinating to watch the evolution of the creator economy on YouTube. That’s why Anthony Padilla is in the film [one half of Smosh, who departed from the company in 2017 for solo projects before returning this year]. By the time they were freshmen in college, they were earning a living in the earliest days of YouTube. When Anthony says he thinks YouTube is going to replace mainstream media, there’s an element of truth to it.

How has the success of YouTubers impacted the film and TV industry?

The thing that YouTube did right — and they don’t do it perfectly — is that they make pretty fair deals with their creators. Admittedly, it’s a monopoly. It’s like if there were nothing else in the entertainment industry but Netflix. It’s as if you had no option other than to negotiate with Netflix. YouTube is owned by Google and could eat every other entertainment conglomerate for lunch without batting an eye. Their creators have way more views than most movie stars, their videos have way more eyeballs than most movies and TV shows, yet they’re not really a content creation company. Because they’re a monopoly, they’re not really incentivized to change their business model. In many ways, it’s been damaging to the entertainment industry. If you package a movie today, you’ll get a cast list from the agency, and the first thing on that list isn’t their credits — it’s their social media reach. I find that so appalling because I’ve been in the industry long enough to know that doesn’t mean anything. Remember the Ain’t It Cool craze?

Oh, god.

Yeah, you do. Everyone thought you had to go down to Austin, then show your movie at Comic Con, and it never resulted in box office. In my opinion, the tech-oriented studios have gotten distracted and inaccurately bedazzled by the numbers from the internet. Those are not the same as box-office numbers. There’s a huge difference between being an influencer on YouTube who can monetize billions of views and why “Mission: Impossible” makes money. I think one of the reasons we’re in a strike is that after the music industry crash post-Napster, Hollywood thought, “Oh my god, the consumers are all online, there’s billions of them, and we want these big numbers. Let’s promote everything on streaming.” But the ecosystems are so different. It doesn’t monetize the same way it does on YouTube or another platform. They’re not the same. This really hurt our industry. People got really dazzled by the allure of these numbers and in our industry those numbers don’t result in profit.

The flip side of all this: YouTube allows people to monetize their work off views — which is essentially what actors and writers are asking to do. So could the YouTube ad-share model provide a path for resolving the WGA and SAG strikes?

The problem is that I’m not certain the businesses are similar enough to do that. It wouldn’t appeal to most Hollywood creators to become more like YouTube. I have friends in the tech space who suspect Amazon and Apple may begin to do this moving forward by allowing content creators — and I hate that term as much as anyone, it’s vile, but it’s what they’re called — to upload their own content and monetize that. But I’m telling you the problem with that is that you’re basically abandoning the entertainment industry as we know it in favor of an influencer-creator industry. They’re not the same.

So you don’t think Hollywood should become more like YouTube.

When the strike happened, I started to hold these meetings with AI experts to try to educate people a little bit. I held them over Zoom and anyone could show up. There was a talk we had with the head of machine learning at CalTech. We had one Oscar-nominated director show up. These scientists are not all doom and gloom. They think we’ll get through this, figure out AI, and it’s not the end of the world. This director was like, “Why isn’t this the end of what I do?” And the guy said, “You should just embrace this technology and use AI to engage with your audience.” The look on her face — she was so mortified! We tried to explain to him, “You don’t understand, we don’t want to do that, we don’t tell stories this way.” I think that’s really at the heart of the strike. You’ve got these kind of newfangled distribution and production entities — Netflix, Amazon primarily — who don’t really understand what we do. We’re not gig-working content creators.

I am afraid that things are going to shift more away from what we want culturally toward a creator economy that resembles the way the internet has been built. That would be very sad. Movies like “Oppenheimer” and “Barbie” show you that the public doesn’t even agree with that. You can’t have an old-school movie and TV industry over here, and this whole YouTube blob-thing over there. Right now there’s a confusion within our industry that we have to drive toward what the internet is doing.

I’m sure you know that famous Frances Ford Coppola quote about how one day some little girl in Ohio will pick up a camera and become the next Mozart. Isn’t that the democratizing force that YouTube and other platforms like it provide? Sure, there are conspiracy theorists and crazy people, but it still levels the playing field for creatives.

I have a lot of respect and hope for the democratization of content creation. My concern has always been the avaricious incentives of those in control — the new boss is worse than the old one. That’s what we saw with the music industry. Sean Fanning’s vision for Napster was a democratization of music where artists got paid equitably for their work. The exact opposite has happened. Snoop Dogg came out recently comparing the WGA strike to his industry and how he can have a massive hit record that makes him almost no money now. So I like the idea of what you’re saying, and I’ve supported an enormous amount of YouTubers who are filmmakers.

But my concern is that we will have these strangling monopolies that don’t adequately pay. That is an issue with content creators and the content ID copyright flagging system they have. A lot of creators are afraid to dispute these claims because then they can get their channels killed. In general, though, I agree with you. The reason I’m attracted to stories of the internet is its ability to remove gatekeepers and let people tell stories. I credit YouTube with driving the diversity initiatives that the wider entertainment only picked up out of fear of losing audiences. Way before our industry, YouTube was giving trans people, people of color, and people from foreign countries promotion for their channels. They really put their money where their mouth is and many channels became huge. It’s a mixed bag, but there is a lot of good. I find that Coppola quote amusing — and I love Coppola — but the guy has made $100 million movies his whole life, including right now! That’s what we were saying to these AI guys: By its nature, film is more like architecture. You’ve got to build this giant thing that requires resources and equity. You may start off with the little girl in Ohio, but eventually she wants to make a Marvel movie. Can we have an industry to support that? Right now, we don’t. That’s why people are freaking out.

A few years ago, some YouTubers tried to unionize. It wasn’t successful. Do you think there’s a path for that?

This is my big issue. We mentioned it by way of Ryan Kaji of “Ryan’s World” [a children’s YouTube channel hosted by a child]. His dad talks on camera about how there’s no regulation for these kids, no union, no following of basic child labor laws. That’s why you have someone like Lil Tay. You don’t know what’s going on with these kids and whether they’re safe or not. Just take something like that and expand it across everyone in that space. I think there will be standards and practices in the long-term, guardrails that make sense. It’s going to take time. You have to remember that Google runs YouTube. It’s not a separate company. Only like a week ago, Google got dinged for illegally getting rid of AI workers who were trying to unionize. I think it’s going to be a fight. Google is not going to be too amendable to that happening. There’s literally nowhere else for these creators to go. This is the only media portal for all of this content. Until they face some form of competition, they’re going to fight this tooth and nail. They have a huge audience. So how democratic can it be when the ecosystem is a monopoly?

Part of what we’re seeing now is that all content consumption has collided. Kids keep the TV on while swiping through TikTok and it’s a mixture of their friends, amateur clips, professional stuff, whatever. It’s all one experience. The industry can’t make sense of such convergence.

In a way, that is why we need gatekeepers for certain types of culture. I came up by auditioning as a kid, not getting certain things, then working on my craft to make it better. That’s how this thing works. Without those gatekeepers, I wouldn’t have had a career. I would’ve been like, “Who gives a shit, I’m just going to get my iPhone and make my stuff.” When Twitter got bought by Musk and killed, it broke into a million pieces. A lot of famous people on Twitter said they were getting tired on social media anyway and it felt like it was going to end. But that’s not what’s going to happen. Now I find those people on Mastodon, Threads, wherever. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. We don’t need one central system. That’s the big fuckup Hollywood made with streaming. Let the internet be the internet. Let some kid from Ohio get famous on YouTube and if she wants to, go make art films, and let the art house distributors have a business model they can monetize off that. People can cross over from one ecosystem to another. We don’t want just one. A lof of people are going to leave this industry for lack of being able to sustain themselves and they’re not going to come back.

As usual, I welcome feedback to this column: eric@indiewire.com