Isabelle Huppert isn’t always an actress who disappears into her roles because, like perhaps her American counterpart Meryl Streep, her presence is already iconic and bigger than the screen itself. But in Jean-Paul Salomé’s “La Syndicaliste,” she goes full Hitchcock-blonde, bangs and all, to play Irish whistleblower Maureen Kearney. A trade unionist who exposed corruption at multinational nuclear powerhouse Areva in 2012, Kearney was violently assaulted in her own home after she brought to light secret dealings with China, but police and press didn’t believe her, and she was accused of staging her own attack.

While the story was widely publicized in Europe, Huppert herself wasn’t familiar with Kearney’s case. Kearney, forced into confessing to fabricating the assault after a brutal and longwinded police custody, eventually retracted her statement and was cleared of charges. But “La Syndicaliste,” even if you know the story, still plays like a thriller that leaves you questioning Kearney’s motives. As seen in the film, she’s obsessed with crime fiction, highlighting passages in pulp thrillers, with Huppert filling in the spaces to create an unreliable narrator even as she’s eventually vindicated. In other words, it’s another typically dangerous role from the Oscar nominee.

Huppert, in conversation with IndieWire, didn’t draw the explicit connection from this film to “Elle,” the 2016 Paul Verhoeven drama in which she plays a rape victim who doesn’t report her attack because of her own troubled relationship to law enforcement. Both films present an unsteady portrait of victimhood, which Huppert said aligns with her “natural approach” to complex characters like Michèle Leblanc in “Elle” or sexually masochistic musician Erika in Michael Haneke’s “The Piano Teacher.”

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.Kino Lorber opens “La Syndicaliste” in select theaters December 1.

IndieWire: Did you know the story of Maureen Kearney before you took on this movie? You’re playing an Irish woman to whom all of this actually happened in France.

Isabelle Huppert: It’s a film, so you can also take it as a fiction, and fiction goes further than reality in this case in particular. I had never heard about the case myself. It happened in 2012. Until I read the book and screenplay, I’d never heard about it before. It had been publicized at the time it happened. Most people who discovered the film said they’d never heard about the case before, so I was not the only one to be absolutely oblivious to the case. But then I read the book, which was written later. The book was telling the whole story with many details and input.

Did you meet Maureen during pre-production, and how important is that to you as an actor when you’re playing a real person?

In fact, I didn’t meet her. It’s not important for me. A true story becomes a film, you have to take your own imagination to do the job, and I wasn’t particularly inclined and didn’t particularly need to meet her. But I went further than meeting her. I completely stole her physical appearance, the way she was made up, her clothes, her hair color, her glasses, and it was in fact, Jean-Paul Salomé’s idea in the first place to really try to resemble her because she has a cinematic appearance, almost like a Hitchockian kind of heroine, with blonde hair and glasses, a little bit strange for a syndicaliste. So we immediately said, let’s not go any further; just try to stick to that physical appearance, so it was more than in fact meeting her, because I really look like her in the film. Eventually, she came to the set, and we did talk a little bit, and as things went by, I got to know her more and more because she was quite inclined in the promotion. She liked to present the film, she liked to speak about her case, and that might have been part of the reconstruction of her personality.

And she’s happy with the movie?

Although I took some, I wouldn’t say liberties, but I did my own interpretation and decided also to emphasize certain aspects more than others, but when she saw the film, she was happy, I think.

Maureen has a very specific look in real life, but there are a number of shots in the movie of the back of her hair that look exactly like Kim Novak in “Vertigo.” I imagine that was probably intentional. It puts you immediately into a place of questioning the character and the narrator.

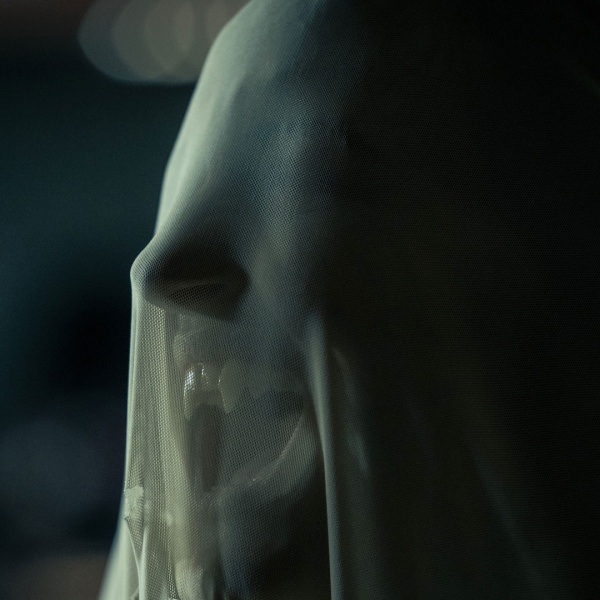

That’s what was interesting about the film. She was twice a victim, a victim of the aggression, that goes without saying, and eventually, in the second time, she was the victim of being not known and of suspicion. Not only was she arrested, but then she had to face that suspicion, which was deadly, because that’s what led her to in the first place to give up everything and say for many years, “Yes, I was guilty, yes I made up the whole thing.” It’s only four or five years later that finally she decided to go back to fight. Because of this, I was interested as an actress to show almost a double face, to show the face of those who believed her and to show the face of those who did not believe her. So it was interesting for me because there was room and space to build up a kind of complex character with some kind of obscurities darkness, something slightly incomprehensible about her, and to make her a little strange. And that was, of course, it made the character much more interesting for me.

There’s a moment where she’s just had a gynecological exam and then she’s singing to herself in the mirror, reapplying her lipstick. It’s a strange sequence. What did you make of it in the script?

She is accused from the very first moment of not being a “good victim.” Of course, the lipstick, which apparently strikes a lot of people, was the first indication, a first sign of this being not a “really good victim.” You can also read that gesture in many ways, like a mask, like something with no explanation, which is always mysterious, when you can’t really explain something. The more you can’t explain, the more you build up some fantasies. It was also an indication of how strong she is also because, yes, she does not show many signs of pain and suffering.

I don’t know if it’s true that she’s obsessed with crime fiction, but this is a great cinematic device.

I was helped with this with the script and with directions that Jean-Paul Salome took from the writing, so in fact I never asked her if that was her reality, if she was interested in thrillers herself. Probably he took that from her because he got to know her quite well as she was writing the script. Maybe that was in the book also, but it certainly builds up a thriller atmosphere in the film.

How hands-on do you get with the costume and makeup of a character?

It’s essential, even if it’s nothing or a lot of things, something very visible, something particularly invisible, it’s essential. That’s the real preparation, the construction, the first indication to an audience. Everything is telling, the little details, even though it’s unconscious, she’s like this or that. Unconsciously, you receive an appearance, the way to walk, and it’s very important. Of course, I don’t do it myself, I do it with the costume designers. As for the preparation of the role itself, there is nothing to prepare, a lot of thinking, like a dream that comes through in your mind, and then you do it when you do it. That’s the strength of cinema only.

Did you draw a connection from this film to “Elle”? Both take a strong look at how victim narratives get doubted, manipulated, reconstructed.

I was never aware of this when I did the film, when I read the script. But of course, when the movie was released [in France], a lot of people came up with this connection between the two films. In “La Syndicaliste,” it’s a rape but it’s not a rape like in “Elle.” I took it more as an aggression. Of course, it’s sexual assault, like a rape, but it’s more a physical aggression. The way she reacts, there are some similarities, the way she’s not a good victim. I didn’t think about it before which makes it even more obvious because it’s my natural approach to the subject without even making it conscious. [Laughs]

I talk to European actors and filmmakers where a lot of film projects are state-funded, and it feels like cinema for cinema’s sake is thriving a little more than it is here, where filmmaking is a lot about appeasing stakeholders. What determines the kind of projects that you take on now?

What I’m looking for is still a dialogue with a director. I still believe in this, and I hope that doesn’t become obsolete, because that’s not what you have when you make a series, where you have different looks. At the end of the day, do you have one look, because you have several directors? I’m not saying it’s against cinema but, certainly, do you have a vision, a very personal vision of the film? You have the vision of a script, of a screenwriter, a series of events, a series of good scenes, but do you have an aesthetic vision? For me, that remains the definition of moviemaking. That’s what I look for, a director.

If you take any of the films, I’ve been doing. What would “Elle” be without Paul Verhoeven? What would “The Piano Teacher” be without Michael Haneke? I wouldn’t do “Elle” without Paul Verhoeven, or “Piano Teacher” without Michael Haneke. It’s the original, visionary point of view that makes me willing to do it, but also possible for me to do it, because it relies on trust and confidence, and I can only trust people like them.

You recently announced a project with Dario Argento. What’s the latest with that?

I hope it will happen soon. It’s a wonderful script and story. It’s a wonderful idea, first. But I can’t say more. The idea is just that Dario and I will be working together. I’ve seen many of his films and, yes, I’m a longtime fan of his cinema. I think we can be a good team, him and me.