In the opening moments of “Janet Planet,” Annie Baker‘s understated miracle of a directorial debut, a young girl runs across a darkened field into a seemingly abandoned structure. She picks up the phone in the dimly lit wooden room and makes a shocking claim: She’s going to kill herself.

It’s a disorienting statement that makes the viewer immediately question what exactly this film is or may become. It also turns out to be a wry joke that serves as an introduction to Lacy (newcomer Zoe Ziegler), the wonderfully peculiar preteen whose perspective is the movie’s engine.

Lacy’s threat, it turns out, is an empty one. She just wants her mother Janet (Julianne Nicholson) to come pick her up from camp where she’s feeling like an outcast and uses an overly dramatic ploy to get what she wants. Janet, who gives the film its title, obliges, and it’s the first glimpse of the fascinating and idiosyncratic codependent relationship that Baker brings to life in her first feature.

“Janet Planet” is gloriously packed with the carefully observed details of the lives of its central characters, who are embodied with warmth and endearing strangeness by Ziegler, an incredible discovery, and the typically fantastic Nicholson, who gives one of her finest performances to date. It also marks Baker’s transition from heralded playwright into major cinematic voice.

That pivot is not necessarily an easy one to make — the stage and the screen often required different skill sets for both writers and directors — but Baker, a beloved fixture of Off-Broadway, has always seemed uniquely suited to the challenge. Her lauded work defies theatrical standards and, as a bonus, she’s long shown an interest in the world of movies. For instance, her Pultizer-Prize winning endeavor “The Flick,” is a three-hour portrait of the employees of a rundown movie theater in Massachusetts that is filled with long silences where the characters simply sweep.

Like that play, “Janet Planet” is also keenly attune to the power of quiet, of just watching people do things. Set in the summer of 1991, its structure is defined by three people who Janet invites into her and Lacy’s lives. The first is Janet’s gruff boyfriend played with unnerving silence by Will Patton; then comes Sophie Okenedo, a bubbly friend emerging from a toxic relationship with a thespian commune, led by Elias Koteas, who eventually ingratiates himself to Janet as well. The world Janet, an acupuncturist, occupies can only be described as “crunchy granola” — she resides in a wooded area, is suspicious of antibiotics, and wears her quasi-hippie, all-natural aesthetic gorgeously. She’s easy to talk to and comfortable in her own skin. Lacy, on the other hand, is not.

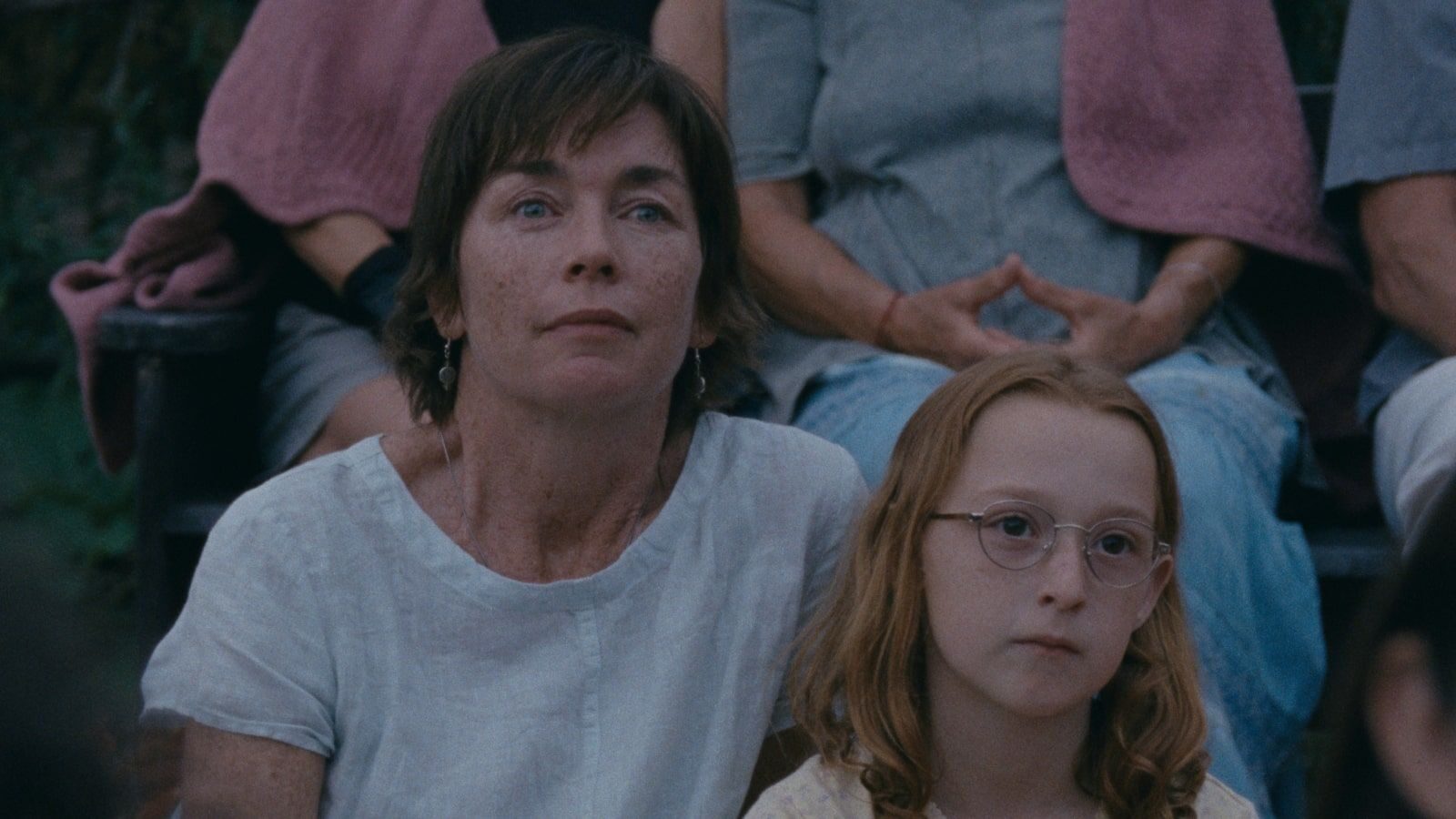

With glasses and frequently pursed lips, she’s an awkward girl who fills her life with little rituals, like tending to a bedroom shrine of figurines, kept hidden behind a curtain, to whom she gives offerings like squeezes from a juicebox. She is at the age when people typically start to drift from their parents, but instead she holds onto her mother tightly, literally and physically. Although Janet resists, Lacy wants to still share a bed with her mother.

Their dynamic is an inversion of the one we’re used to seeing between mothers and daughters in movies, where the former wants to control the latter and keep her from leaving the proverbial nest. Here, it’s Janet who is growing frustrated by Lacy’s clinginess, as evidenced by Nicholson’s subtle work, a hint of exhaustion creeping over her face in small moments like when Lacy insists on having a “piece” of her mother to sleep with.

Lacy, meanwhile, is not only trying to keep herself at the center of her mother’s affections, she’s also trying to understand this woman, and in turn womanhood at large. Ziegler’s face has an inquisitiveness as Lacy tries to puzzle out just why people keep glomming onto Janet — and why Janet keeps allowing them too. Baker follows this odd, lonely duck as she marches to piano lessons and takes solo journeys to get ice cream. Though there’s sometimes little dialogue, you can feel this still somewhat unshaped mind constantly whirring as it deciphers its own disappointments.

Working with cinematographer Maria von Hausswolff, Baker uses 16mm to create a wistful haze of nostalgia that is punctured by Lacy’s budding cynicism. In their compositions, energy beams off of Nicholson, who has a tricky task at hand that she pulls off spectacularly. In the eyes of so many of the other characters, she’s luminous, but she’s also wracked with self doubt. Rarely do we see her without Lacy’s gaze nearby, and Nicholson manages to create a fully formed character even with the intentional limitations of that viewpoint.

Baker and her production designer Teresa Mastropierro pack their frames with such care that you can almost smell these spaces — the armpits lacking in deodorant, the herbal shampoos, and the musty books. The costumes, by Lizzie Donelan, have a similar effect. Janet wears long skirts, while Lacy is constantly in oversized t-shirts. Her look is not exactly tomboy. It’s more generally undefined.

There is nothing artificial here, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t mystery. It’s the mystery of people and their unusual behaviors and the way they can flit in and out of our lives and our consciousness. A girl like Lacy is a mystery even to herself at this point in time, but she’s slowly on the path to figuring it all out. There’s also magic here — in the environment, in Janet’s allure, and in Baker herself, a talent defining herself in a new arena.

Grade: A

“Janet Planet” premiered at the 2023 Telluride Film Festival. A24 will release it at a later date.