“Red, White & Royal Blue” is getting down and dirty — and redefining queer intimacy onscreen in mainstream films.

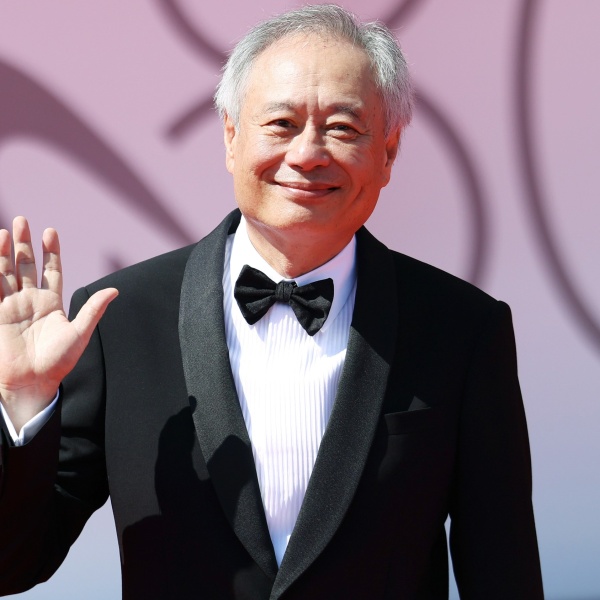

The Prime Video adaptation of Casey McQuiston’s bestselling novel is among the few recent R-rated queer rom-coms. Directed by Tony Award-winning playwright Matthew López, the film stars Taylor Zakhar Perez as Alex, son of the U.S. President (Uma Thurman) who has an enemies-to-lovers whirlwind romance with British Prince Henry (Nicholas Galitzine).

It’s not just about two hot men falling head over heels; according to intimacy coordinator Robbie Taylor Hunt, “Red, White, and Royal Blue” exemplifies the importance of having queer below-the-line experts to stage, well, accurate queer sex scenes. Below, Hunt discusses the intersectionality of LGBTQ love onscreen with IndieWire and how that sultry Paris scene came to be.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

IndieWire: “Red, White & Royal Blue” is such a beloved novel with a very memorable pent-up romance. Did you use the outlined sex scenes on the page to block the big-screen adaptation?

Robbie Taylor Hunt: It’s an interesting question because if you look at the canon of sex scenes and eroticism in fiction texts like novels, there’s just a certain way that that’s kind of approached. You can make a little wry comment which paints a very vivid imagination. You don’t need to say that much. The book has got some good erotic moments and that’s painted beautifully but when it’s something you’re imagining in your head, that’s a different kettle of fish. As an intimacy coordinator working largely in TV and film, theater as well, you are seeing that. You are seeing images of people who are doing acts or performing a level of nudity. You have to approach that quite differently. Whilst the book is brilliant in the sense and quality and the tone and the connection and what we want to see for the dynamic between the characters and the fans, you are aware of that. But then you just have to come with a slightly different mindset knowing it’s a visual media.

I will admit that I knew about the novel but hadn’t actually gotten around to reading it, so then as soon as I was going to be meeting with [director] Matthew, I quickly devoured the audiobook and had so much fun. It was brilliant. It was just so fun and playful and some real joyful silliness to it. My little gay heart was aflutter with it all.

The chemistry between Alex and Henry is palpable. How did you choreograph their more emotionally intimate moments, and was there a sex scene you are most proud of?

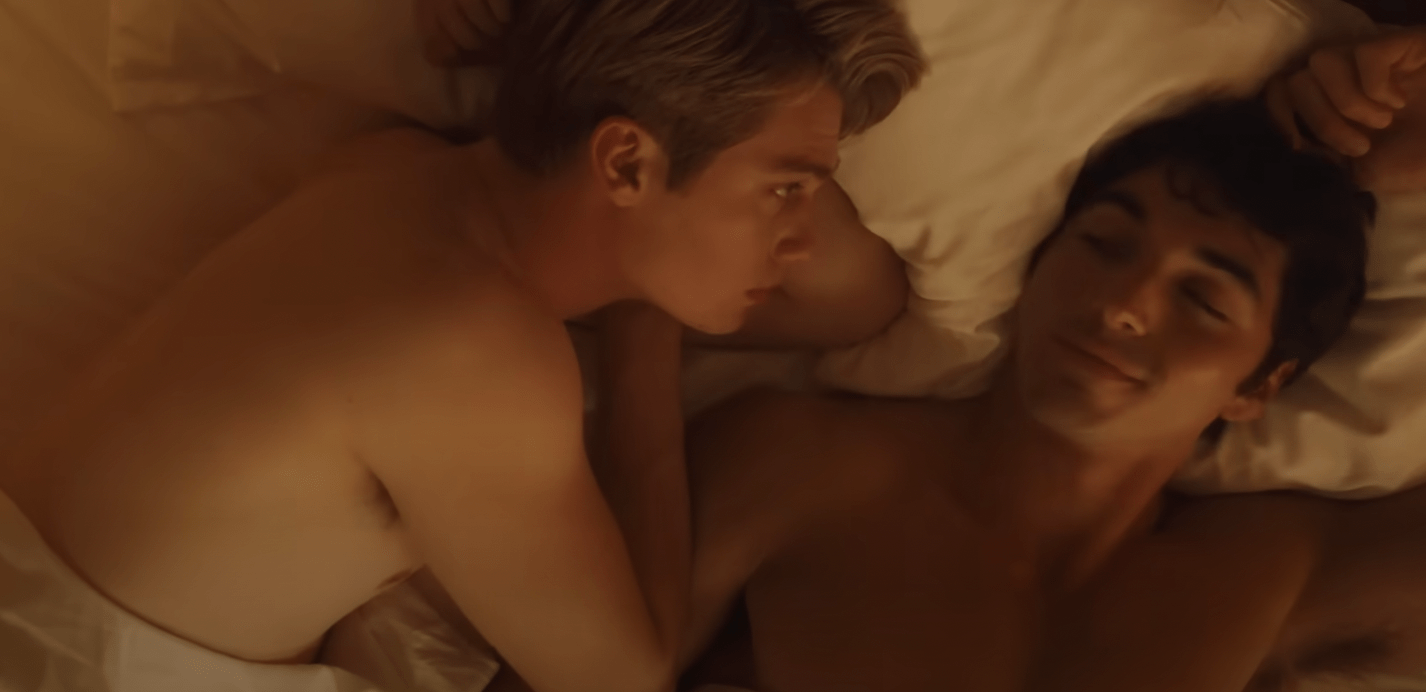

Definitely most proud of and spent the most time and creative energies and efforts on the Paris scene in bed, just because that is such a major moment for the characters and their journey. I’m a queer intimacy coordinator and working on queer intimacy onscreen is just really important to me. So any chance I get to work on a moment that feels new or a chance to show queer intimacy we haven’t seen before is exciting. I think that scene does that, just by nature of what this moment is between characters. I don’t think we get a lot of good loving, detailed, dynamic character-driven moments of sex between men onscreen in big films like this. It was a real sense with everyone onboard of wanting to do it right and serve that moment well, which is so central for these two characters in different ways.

Did you closely work with the cinematographer or director to know which close-ups would be used and when?

As an intimacy coordinator, particularly because it’s still a fairly new role, how people engage with us can be vastly different. It’s a creative industry and we’re working with creative people; there’s going to be a big differentiation from one project to the next with how they work with us. Generally we quite like a lot of specificity because when we’re in the world of simulated sex or nudity, there’s modesty garments and barriers and things. The equipment that I use in those scenes will slightly depend on what shots we’re doing, like if we’re seeing two characters from one angle, they need to be in certain modesty garments and use certain barriers. So I tend to try and get as much information as I can around those sorts of things just so that I can do my job properly and the actors can be properly prepared. Because if I say we’re doing the sex scene and it’s nearly entirely shots of your face and your hands, that’s one thing. If we say we’re doing the sex scene, it’s entirely played in a wide [shot] from one side and a pop shot wide down, that’s a very different thing.

In the wake of films like last year’s “My Policeman” and Ira Sachs’ “Passages,” how has your role as a queer intimacy coordinator changed in recent years, especially with the debates over showing sex onscreen in general?

It’s so interesting. Welcome to my TED talk. My position obviously as an intimacy coordinator, I’m here to protect the actors [and] safeguard the actors’ work with a consent-based practice within their boundaries as one side of things, an essential side of it. But I’m also creatively a movement professional with movement language and techniques and skills and choreography to create moments of physical storytelling which are dynamic and exciting and further the character’s story and the narrative. Moments of sex and intimacy can be really dynamic, a space rife for meaning because that’s where someone might be at their most vulnerable, where they might be performing a different version of themselves or having a new moment of connection with someone that they haven’t had before. It’s just an exciting space. I’m all about properly embracing those moments. And that doesn’t mean, as we’ve seen in lots of films, showing something very “explicit,” or something which feels sensational, like you can tell a whole story of intimacy with facial reactions. I’m not saying I want to see it like I need to see loads of really long, huge sex scenes, loads of nudity.

But I think that’s even more true of queerness onscreen, which offers moments that are really exciting and essential character moments. A lot of people’s queerness will be found in romantic and sexual interactions and that will then speak to a queer audience. Queer audiences will crave and want to understand and see those moments because they’re important in our lives. In a largely heterosexual culture, TV and film has this sort of straight gaze on it. It’s always, “Let’s be careful about how much we show because we don’t want to spook the straight people” or “And then they have sex and I don’t know exactly what that looks like or I don’t know exactly how it sort of clashes with my idea of what queer sex is or what is right for these characters, so let’s sort of pan away to the window or whatever.” There is a slight discomfort in how to do it right. I think most queer sex onscreen has come into conflict with the straight expectations of that, leaving queer viewers frustrated with either the lack of representation or inaccurate representation.

Without queer intimacy coordinators adding to the pool of queer knowledge in the intimacy community, heterosexual cisgender intimacy coordinators need to have that kind of respect and appreciation of how to do queer sex. We want this to be realistic. Let’s talk about what the beats are like that are going to alienate viewers. It can’t just be vague or inaccurate or fall into harmful stereotypes of what queer sex looks like or needs to be.

Do you think non-queer intimacy coordinators should be able to choreograph queer sex scenes, much like how queer actors are saying straight stars should not portray gay characters?

My personal opinions have changed and I’m sure will continue to change. I completely respect that other people might have different angles on this, but my kind of big picture thing is that part of all of our jobs as intimacy coordinators is to have an understanding of different types of sex that aren’t relevant to you. There are very few intimacy coordinators who have done every type of sex in their real personal life. I think with the intimacy coordinator community growing, there is a real sense of continued professional development and sharing and connectivity. There’s been workshops on trans intimacy and gender non-conforming intimacy. I think that you can improve your knowledge so that you’re prepared, particularly thinking like, “I might be the intimacy coordinator on a TV show across a season where there’s all types of intimacy in it. I have to be prepared to work on lots of different things.”

My little caveat is it depends a little bit on the makeup of the team. So if there was a very heterosexual team creating a queer moment and then there was a heterosexual intimacy coordinator brought in, maybe that production could really afford to have an extra bit of a queer perspective with a queer consultant or something. There are roles particularly for that as well. I think it’s complicated because our big thing with intimacy coordinators is personal professional boundaries, right? We don’t ask the actors to have to bring any of their real personal intimate lives to perform. So it feels a little bit hypocritical to say to your intimacy coordinator, “How much queer sex have you done? I need to know before you’re allowed to do this thing.” I’m being reductive there. It’s not as simple as that. But I think we just need to be intersectional and look at it in a complex contextual professional way and be honest with ourselves and with what the production is and what the team needs and just look at it with a kind of multifaceted eye very quickly.

“Red, White & Royal Blue” is now streaming on Prime Video.