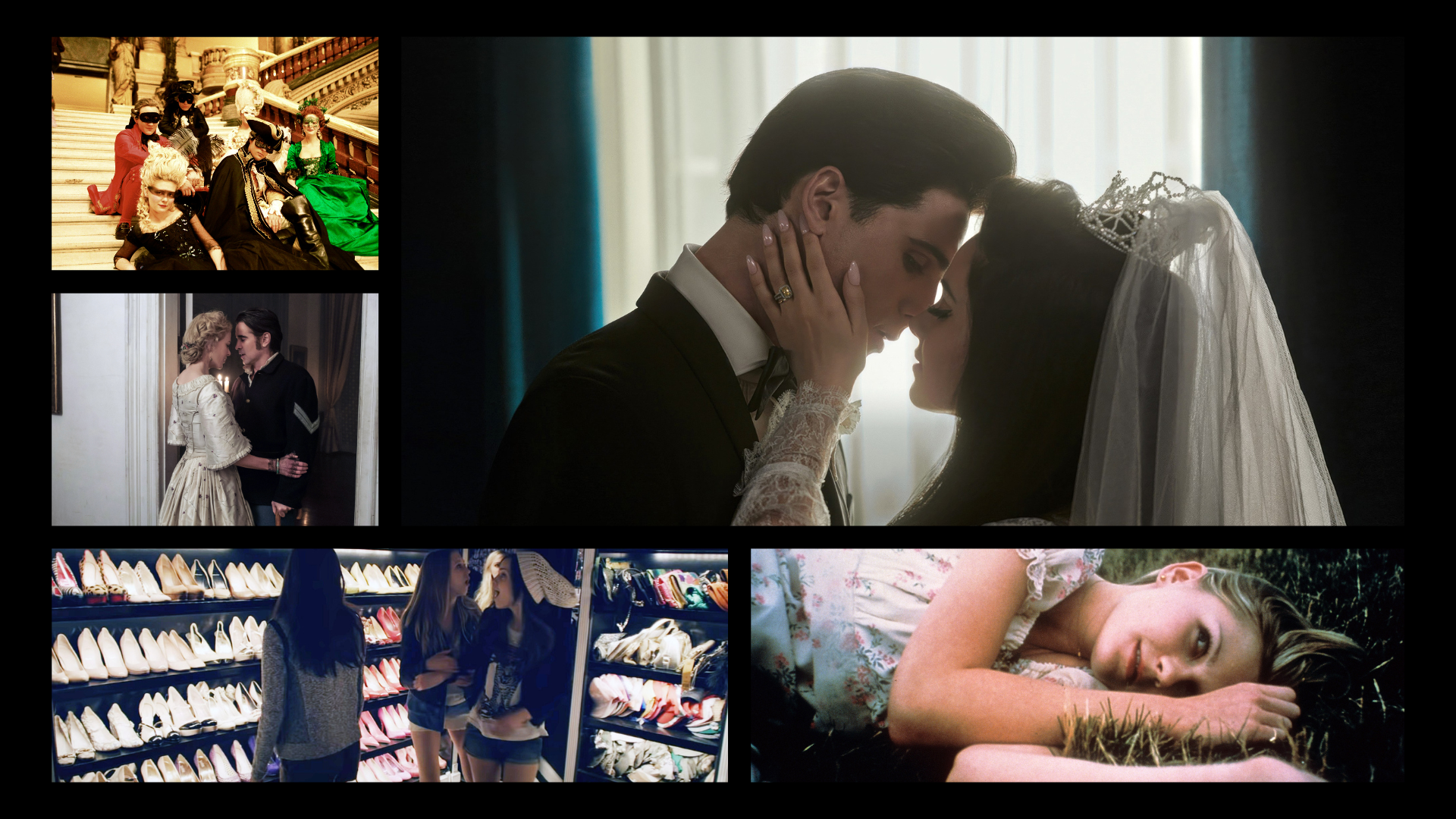

Sofia Coppola movies are defined by desolate landscapes, lonely characters, a wry sense of humor, and painterly compositions. For fans of this aesthetic, it’s pretty hard to get it wrong, and Coppola’s nearly 20-year track record attests to the consistency of her talent. From her feature-length debut “The Virgin Suicides” through “Priscilla,” Coppola’s dreamlike visuals and deadpan tone have remained a distinctive voice in American cinema, one filled with gentle, forlorn faces and a world that always seems as though it’s on the verge of devouring them whole. (If there isn’t already a Reddit forum theorizing that all Coppola movies exist in a single universe governed by the laws of sadness, someone should kick it up.)

While Coppola’s career was set in motion to some degree by the influence of a very famous father, her filmmaking capabilities are hardly dictated by Francis’ accomplishments. The tough, masculine sagas of “The Godfather” and “Apocalypse Now” exist a world away from Sofia Coppola’s intimate portraits — all of which, it must be said, feature strong-willed women. In May of this year, Coppola became the second female director in history to win Best Director at the Cannes Film Festival, and you couldn’t ask for a better filmmaker to make up for lost time. The hallmarks of her style reflect a complete artistic vision.

All of this is to say that a ranking of Coppola’s movies from “worst to best” should not imply that a single bad movie exists in Coppola’s oeuvre. At the same time, Coppola’s storytelling approach has found her tackling a range of subjects over the years with varying results, some of which are more wholly satisfying than others. Nevertheless, chances are strong that if you’ve responded to one Coppola movie, you’ll find something rewarding in all of them, and will find that the process of examining her entire body of work offers even more riches than any single movie can provide.

With the release of “Priscilla” marking the first theatrical opening of a Coppola movie in four years, IndieWire took a look at revamping our old ranking of the director’s output. Only feature-length films qualified, meaning her early short “Lick the Star” and her 2017 recording of Italian opera “La Traviata” are not included. Needless to say, Coppola shows no signs of slowing down, and any overview of her accomplishments will likely need a big update in the years to come.

With editorial contributions from David Ehrlich.

[Editor’s Note: This list was originally published in June 2017. It has since been updated.]

9. “A Very Murray Christmas” (2015)

It’s almost a cheat to include this Netflix quickie, a musical revue set in Manhattan’s Carlyle Hotel against a flimsy Christmas Eve plot that’s basically an excuse for Bill Murray to do his thing. On the brink of recording his Christmas special, Murray realizes that the bulk of his guests can’t make it due to a snowstorm, but manages to throw together a lively show anyway by improvising the night away. Standout vignettes include a hilarious, awkward sequence in which he drags a baffled Chris Rock onto the stage for a rendition of “Do You Hear What I Hear?” and Maya Rudolph belting out “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home).” Cheeky cameos from the likes of George Clooney, Miley Cyrus and Jason Schwartzman round out the playful ensemble, and they basically exist to prop up Murray’s marvelous capacity to charm the room.

Unfurling with a loose, freewheeling quality, this is the least Coppola-esque movie that Coppola has directed — until you consider how late-period Murray, with his melancholic gaze and bittersweet embodiment of fame’s alienating qualities, basically owes his existence to “Lost in Translation.” In that context, “A Very Murray Christmas” may be the closest Coppola ever comes to making a “Lost in Translation” sequel, although it’s more like a B-side that suggests even a sad, aging artist past his prime can find some modicum of solace in his art. —EK

8. “On the Rocks” (2020)

Too light to resonate emotionally and too heavy to feel good, “On the Rocks” is one of Coppola’s only films that feels unsure of what it’s trying to be. The tale of Laura (Rashida Jones), a wealthy novelist who ropes in her semi-estranged father Felix (Bill Murray) to help her find out if her husband Dean (Marlon Wayans) is cheating on her, is rife with lingering resentment and bitter feelings but takes the form of a slight comedy of manners. Despite all the intriguing ideas underneath the surface of the film — about aging, fractured family bonds, and upper-middle class ennui — Coppola’s script lacks her usual exacting detail, and the whole thing floats by as a mere wisp of a thing, unable to reconcile the sharper and thornier emotions with its sitcom-like premise. Still, even at her least fulfilling, Coppola’s ideas still intrigue, and Murray’s performance as a charming cad still manages to intoxicate. —WC

7. “Priscilla” (2023)

Priscilla Presley only had a few precious lines in Baz Luhrmann’s “Elvis” (a delirious biopic whose title always feels like it’s missing an exclamation point), and even fewer of them were memorable in the slightest. But, a little more than a year since that movie came out, one bit of Priscilla’s dialogue continues to stay with me for how succinctly it crystallized the film’s conception of her. “I am your wife!” She yells at Elvis, as if he doesn’t know. “I AM YOUR WIFE!” That was all she was in that story. It was no different than if Vernon Presley had screamed “I AM YOUR DAD!” or if Colonel Tom Parker had bellowed “I AM YOUR MANAGER!” (which he probably did).

And that’s fine, I suppose — “Elvis” had its own agenda, and its namesake’s only wife didn’t play a large part in it. But Luhrmann’s spasmodic rhinestone spectacle may have finally served its purpose, as it now provides helpful context for a new film that another major artist has made about The King’s one-time queen. Which isn’t to suggest that Sofia Coppola’s soft and muted “Priscilla” should be seen as some kind of rebuttal to last summer’s orgiastic blockbuster, but rather to reaffirm her decision to frame this claustrophobic marriage story as a gradual process of separation. Not just Priscilla’s separation from Elvis and the endless shadow of his celebrity, but also her separation from her parents, from her own iconography, and from everyone and everything else that tried to define her before she was able to define herself.

Of course, Coppola was never going to approach this story in any other way. Long compelled by the negative space between young women and the worlds they inhabit (a gap that “The Virgin Suicides” described as “an oddly shaped emptiness mapped by what surrounded them, like countries we couldn’t name”), Coppola has made a career out of freeing privileged girls from gilded cages; girls who are desperate to escape the sense that they’re merely disguised as themselves, always watched but seldom seen. From “Lost in Translation” to “Marie Antoinette,” her films have often framed marriage as the purgatorial first step in a heroine’s path towards actual personhood. Her latest feature makes it impossible to shake the feeling that Sofia Coppola would probably have been moved to invent Priscilla Presley if Priscilla Presley hadn’t ultimately found a way to invent herself. —DE

Read IndieWire’s complete review of “Priscilla.”

6. “The Beguiled” (2017)

Coppola’s most straightforward movie to date finds her adapting the minimalist Civil War drama of Thomas P. Culinan’s novel using many of the same beats found in Don Siegel’s 1971 version starring Clint Eastwood, but applies her own expressionistic filter to the B-movie material. The story of a hunky injured Union soldier (Colin Farrell) taken in by an abandoned Virginia girls’ school headed by the domineering Martha Farnsworth (Nicole Kidman) has a premise that wouldn’t seem out of place in a softcore porn film. Coppola seems to acknowledge as much with playful hints at the eroticism associated with Farrell’s arrival as the young, sheltered women in the house begin to lust over him — especially Alicia (Elle Fanning) and Edwina (Kirsten Dunst).

But there’s an underlying eeriness to their attraction, and to the soldier’s ambiguous motivations as he gradually regains his strength, which sets the stage for the darkly comic suspense of the final act. Echoing the household of “The Virgin Suicides,” the movie transforms into a contained story about woman taking control of dire circumstances on their own terms. The tight, minimalist style that carries the movie forward speaks to the confidence with which Coppola enacts her tricky tonal balance, juggling campy extremes and more sophisticated ideas about femininity and isolation that have defined her work from the outset. It’s a taut, entertaining genre exercise with the potential to expand Coppola’s appeal beyond the insular arena of her devout fan base. —EK

5. “The Bling Ring” (2013)

Coppola flirted with the prospects of celebrity in her youth, and her movies have constantly assaulted the destructive impact of fame, but “The Bling Ring” is her most ambitious statement on the matter. Adapted from a Vanity Fair article about teens who burgled the homes of celebrities they admired, the movie sticks close to the perspective of its gushy teens, led by an overconfident Emma Watson. The ease with which the team of five young thieves unearth celebrity addresses and plot their schemes with digital technology speaks gives a cogent identity to the malaise of 21st century youth culture, and it’s spiked with the most outwardly satirical moments in Coppola’s career.

The conclusion, in which the star-worshipers become vapid stars themselves, completes the movie’s cynical vision. While at times a bit too blunt for its own good, this is still a Sofia Coppola movie through and through, and particularly effective at letting its rambunctious anti-heroes run the show. (It’s safe to say they’ve found a more constructive outlet for their boredom than the ill-fated stars of “The Virgin Suicides.”) The final credit for the great cinematographer Harris Savides, “The Bling Ring” turns the architecture of outlandish Hollywood mansions (including a real one owned by Paris Hilton, who cameos) into angular mountains of royalty that the young marauders conquer with ease. Thematically, “The Bling Ring” is a strange, uneven work about the dangerous effects of showbiz, but Coppola’s unpredictable approach endows the overall package with profound concerns for a new generation. —EK

4. “The Virgin Suicides” (1999)

Viewed in retrospect, Coppola’s ethereal debut is something of a mission statement. Her adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel about middle-class suburban teens in ‘70s Detroit is brought to life as a vivid, nostalgia-laden saga in which men recall the women who changed their relationship to the opposite sex for good. The macabre circumstances in which the teen inhabits of the Lisbon household take their own lives is counteracted by Coppola’s poetic approach, which makes the events feel somehow less horrifying than ritualistic, as their inevitable suicide pact symbolizes the tough and unnerving passage into young adulthood. Assembled by ace cinematographer Edward Lachman, the expressionistic colors become extraordinary windows into the teen characters’ shifting moods; laced with a perfectly-curated soundtrack of ’70s tunes, and an original score by Air, “The Virgin Suicides” is a complete immersion into Coppola’s fresh perspective, and it remains a modern classic decades down the line. —EK

3. “Somewhere” (2010)

Coppola’s first film after the tumultuous experience of “Marie Antoinette” is a comparably small movie that returns her to the familiar arena of “Lost in Translation” with another tale of a bored celebrity trapped by the vapidity of a well-heeled existence. But while Murray’s Bob Harris is in the twilight of his career, Johnny Marco (Stephen Dorff) is just getting started. Living in the confines of L.A. Chateau Marmont, he juggles boring publicity obligations with aimless one-night stands, stuck in a superficial loop. While some critics found “Somewhere” too similar to earlier Coppola movies, the movie contains some of the quietest moments in her filmography.

Coppola fleshes out the emptiness of Johnny’s world with exquisite long takes that juxtapose his opulent surroundings with his bored, vacant expressions. Into this somber tableaux emerges Johnny’s 11-year-old daughter Cleo (Elle Fanning), whose affection for her father forces him to confront the meaninglessness that has enshrouded his world. It’s an obvious twist, but Dorff and Fanning have such believable chemistry that they manage to imbue fresh depth into the familiar father-daughter bonding routine, so much so that Johnny’s eventual meltdown after seeing his daughter off to camp feels like the only natural endpoint. Winning the Golden Lion at the Venice International Film Festival, “Somewhere” provided a welcome reminder that Coppola’s recurring fixations had solidified into a key element in her artistic identity. —EK

2. “Lost in Translation” (2003)

If “The Virgin Suicides” anointed Coppola as a major new talent, “Lost in Translation” proved she was just getting started. The fascinating, textured plight of aging movie star Bob Harris and the young woman he befriends at a palatial Tokyo hotel accomplished many things at once: It singlehandedly remade Bill Murray’s career and put Scarlett Johansson on the map; it turned the Westernized vision of Tokyo luxury on its ear; it assailed the advertising industry; it made karaoke seem cool. Both actors were readymade for Coppola’s playful, mysterious romantic comedy, a Kafkaesque tale of two people from different walks of life who find common ground in the sad, lonely world surrounding them. Murray’s face tells half the story, with each crease and cock an eyebrow speaking volumes about his internalized frustrations. But Johansson’s character, a young woman tired of playing trophy wife to her self-absorbed husband, has long been interpreted as an avatar for Coppola’s own experiences in her marriage to Spike Jonze.

Coppola doesn’t deny these characters the possibility of finding their way to a happy ending; but in a masterstroke that has become iconic, she denies the audience the ability to hear the would-be couple’s parting words. This is Coppola’s brilliance in a nutshell — the limitations of language can never convey the boundless possibilities of emotional engagement. We’ll be puzzling over Bob and Charlotte’s final exchange for ages, but its moving implications are undeniable. —EK

1. “Marie Antoinette” (2006)

“This is ridiculous,” says Marie Antoinette (Kirsten Dunst), as she is forced through a morning ritual. The essential response: “This, madame, is Versailles.”

Coppola’s grandest production came on the heels of next-level acclaim for “Lost in Translation” and brought her reputation crashing back to Earth when the movie was booed at Cannes. But of course the French had a problem with this ironic period piece, in which the country’s most famous Queen is reimagined as a grinning party girl whose lavish exploits are set to the likes of The Strokes and The Cure, not to mention Bow Wow Wow’s “I Want Candy.”

With time, however, “Marie Antoinette” has solidified its reputation as a stunning blend of period detail and contemporary mores, as Coppola uses the sweeping backdrop of Versailles to provide a lyrical immersion into the roots of affluence in Western culture. Dunst’s best role to date — at least until “Melancholia” — allows her to transform the former archduchess of Austria into a cunning young woman whose individuality transcends the frustrating rituals of her time and place. (Jason Schwartzman, as the shy and possibly impotent Louis XVI, is ideally cast as her opposite.) Coppola’s only big studio effort to date shows the potential of her vision when given boundless resources and autonomy to spare; the result may have seemed like a tough sell at first, but like Marie Antoinette herself, it has been vindicated by history. —EK