In many respects, the ‘80s are highlighted as a boom period for anime, something perhaps unwittingly foretold by Mobile Suit Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino in his famous “Anime New Century Declaration” — a promo event for the “MS Gundam” compilation movie “Mobile Suit Gundam 1” that unexpectedly drew a crowd numbering in the thousands. The event was emblematic of that coming explosion — anime production reaching newfound scale, finding larger audiences in turn, and maturing as both a medium and an industry. It would be a decade that saw more confident spending, bigger original productions, and a much deeper roster as new creators.

In many respects, the ‘80s are highlighted as a boom period for anime, something perhaps unwittingly foretold by Mobile Suit Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino in his famous “Anime New Century Declaration” — a promo event for the “MS Gundam” compilation movie “Mobile Suit Gundam 1” that unexpectedly drew a crowd numbering in the thousands. The event was emblematic of that coming explosion — anime production reaching newfound scale, finding larger audiences in turn, and maturing as both a medium and an industry. It would be a decade that saw more confident spending, bigger original productions, and a much deeper roster as new creators.

In a retrospective piece about the moment, “Anime: A History” author Jonathan Clements wrote that while Tomino would become a figurehead, his “new world order” would belong to the next generation. It would be a dynamic new age defined by works like the famous Daicon III & IV Opening Animations, made by the artists and anime otaku who later went on to found Studio Gainax; artists and anime otaku like Hideaki Anno, whose canonical “Neon Genesis Evangelion” contains a reference to Tomino’s declaration in its very title.

Tomino’s declaration was also prescient of how fandom was beginning to shape the direction of the industry itself, as the growing video market and the birth of the Original Video Animation — usually attributed to Mamoru Oshii’s “Dallos” (1983) — would synthesize enthusiasm with technological advancements in order to help anime reach a whole new crowd.

In a booklet essay included in Anime Ltd’s release of “Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêmaise,” critic Ryusuke Hikawa observed that until the beginning of the ’80s, the majority of anime feature films were compilations of TV series, and now with increasing frequency the audience of anime such as “Space Battleship Yamato” and “Gundam” would become creators themselves in an era where more original anime films would find their way to theaters.

Aesthetic developments would follow in turn, displaying themselves in more lavish film production as well as the first signs of 3D animation, like in 1983’s “Golgo 13.” The international proliferation of “Star Wars”combined with the success of works like the aforementioned “Yamato”and “Gundam”factored into a general tilt toward science-fiction.

While general audiences might associate the anime of the ‘80s with “Akira” and Studio Ghibli efforts like “My Neighbor Totoro” and “Castle in the Sky,” the real story of how the industry evolved over the course of those 10 years is best told through relatively lesser-known films that made a massive imprint from inside Katsuhiro Otomo and Hayao Miyazaki’s shadows. The 10 features listed below — presented in chronological order — are representative of the gradual changes and emergent talent that defined the decade, or what Tomino would call “the new century.”

-

“Space Adventure Cobra” (dir. Osamu Dezaki, 1982)

Image Credit: Toho Tawa Animation legend Osamu Dezaki’s “Space Adventure Cobra” is a pulpy romp and a real feast for the eyes as well. It’s a solid introduction to the artist’s incredibly broad body of work, one whose pioneering techniques and visual language are still broadly in use today.

The rakish space pirate Cobra has been presumed dead for two years, evading a gigantic bounty on his head by entirely changing his appearance. His chance encounter with the bounty hunter Jane eventually blows his cover, and his enemies pursue him once again as he attempts to help Jane in her fight to protect her home planet of Miros.

It’s a tragic story, but Dezaki keeps things from feeling dour despite some rather shocking gut-punches. Cobra’s can-do attitude goes a long way, as does Dezaki’s playful visual experimentation. One sequence uses psychedelic, warped frames to depict the allure of a club, while another sequence refracts different paintings across the background. Elsewhere, Dezaki toys with split-screen drama and the use of striking, almost impressionistic insert shots even during the height of the action.

Even with the rather silly cigar-chewing protagonist who lends the film its name, “Space Adventure Cobra” is a weird and romantic “Star Wars”-esque space opera full of cosmic mysticism. The latter comes from Jane and her sisters, whose love becomes a tangible power that intertwines minds across the infinite void of space-time.

-

“Arcadia of My Youth” (dir. Tomoharu Katsumata, 1982)

Image Credit: Toei Company Essentially an origin story for the late Leiji Matsumoto’s 1977 series “Space Pirate Captain Harlock,” “Arcadia of My Youth” is also one of the coolest anime films of the early ‘80s. Directed by Tomoharu Katsumata from a story by Matsumoto, “Arcadia” feels like a riposte to the experiences of the latter’s youth; to “an era when the idea of living life on one’s own terms was unthinkable, even treasonous,” as writer Matt Alt described it in his recent obituary for Matsumoto. This new backstory for the swashbuckling revolutionary Harlock is but one part of the “Leijiverse,” the umbrella term for the overlapping fictions by Matsumoto, but it makes for one hell of an introduction to it as well.

The narrative is intensely interested in how violent history might repeat itself, broadly likening the intergalactic Illumidus empire to the Nazis as the Katsumata’s characters are caught between hope for the future and repetitions of a tyrannical past. The film evokes the French resistance to the Nazis in its depiction of the Earthian resistance to the Illumidus, while several of its design elements boast a similarly atemporal quality (one spaceship resembles a Zeppelin with a pirate’s galleon instead of a cockpit, while Harlock’s laser rifle is shaped like a cutlass).

“Space Pirate Captain Harlock” was already a well-established series by 1982, but “Arcadia” leverages that foundation in order to function independently, as it (slightly) reworks the main cast’s origins and redraws their connections to each other in order to create a space opera that’s as beautiful as it is hopeful.

-

“Barefoot Gen” (dir. Mori Masaki, 1983)

Image Credit: Kyodo Eiga A film that’s leapt back into the public consciousness thanks to discourse around Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer,” “Barefoot Gen” might be the most visceral of movies about the human impact of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. Directed by Mori Masaki (who had also directed the 1986 film “Time Stranger”), the film is an adaptation of Keiji Nakazawa’s 1973 manga, and based in part on the author’s own experience as a survivor of the blast. Similar to the manga, it views the aftermath of the Hiroshima bombing through the perspective of a child, Gen, forced to scavenge and fend for his surviving family in the ruins.

Its most infamous scene is concerned with the bodily horror of the bombing, its vast destructive scale brought down to a disturbingly intimate level. The narration operates in almost documentary-like manner — later unspooling the “second terror” of the bomb and the radiation poisoning, radioactive rain, and pollution that lingered.

But it’s not only about the horror of that moment, but also the ensuing rage directed at the imperialist government of the time, as the film contrasts speeches about protecting that system with images of the charred remains of Gen’s family and his home. Masaki also makes room to include Nakazawa’s depictions of perseverance: Gen swears to build a house on scorched soil, and Masaki ends the film with observance of new grass growing. That hopefulness would extend to the film’s 1986 sequel “Barefoot Gen 2,” which continues Gen’s journey a few years in the future.

-

“Macross: Do You Remember Love?” (dir. Noboru Ishiguro, 1984)

Image Credit: Toho A retelling of the series “Super Dimension Fortress Macross” (infamously adapted into “Robotech” in the U.S.), “Macross: Do You Remember Love?” was directed by series director Noboru Ishiguro and series creator Shōji Kawamori, and it’s as wistful as it is visually awe-inspiring. As is custom for the 41-year-old franchise, it fuses sci-fi and J-pop, romance, and high-flying action, just as Kazutaka Miyatake and then-24-year-old Kawamori’s mechanical design fuses mechs with space-faring fighter jets.

Despite its dystopian setting — the Earth has already been blown to hell by the time we meet the cast — the film has a purely utopian perspective on music’s power to drive culture and culture’s power to shape society at large. It has a lot of fun with mech combat and celeb culture existing in close proximity, as seen in a sequence where the characters come face to face with giant aliens who don’t know what a kiss is. The pop art that exists on SDF-1 Macross stands as contrast to the societies that have died without it, reduced to pure function and cut off from access to emotion and empathy.

For newcomers, the SDF-1 Macross is an unfathomably large immigrant ship, so big that a full city exists upon it. It also transforms into a giant, humanoid mech. The maximalist action that transpires around it unfolds with intricate detail and exhilarating speed, while each moment of combat is given a bit of extra flair; the famous “Itano Circus” (a style of animating missile barrages, named for animator Ichirō Itano), makes a memorable appearance early on.

As is the case in all “Macross” series and films, the romance here is inextricably intertwined with its grander narrative. The romance drives Lynn’s music, and that music basically saves the universe, resulting in a jaw/dropping finale where a pop singer performs on the bridge of a warship, missiles flying past in tune to her chorus. “Do You Remember Love?” is not quite a stand-in for that entire show, nor an introduction or sequel to it, but a parallel story. Regardless, it’s an infectiously optimistic, heart-pounding spectacle.

-

“Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer” (dir. Mamoru Oshii, 1984)

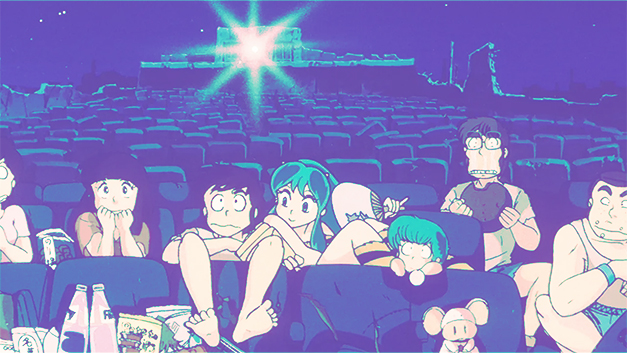

Image Credit: Toho The second “Urusei Yatsura” feature film is a foundational part of Mamoru Oshii’s vibe, folding the trademark slapstick of Rumiko Takahashi’s boy-meets-alien rom-com into a surreal, circular daydream; its cast of idiots is stranded in a bizarre pocket of reality, where time is looping and they have nothing to do but think about stuff.

Despite being a sequel, there’s a surprisingly low bar to entry here — familiarity with these characters helps, but you get a pretty good idea of who they are through ample displays of the franchise’s usual zaniness. Ataru is still an idiotic sleaze, his accidentally betrothed Lum is still electrocuting him in “divine retribution” for his womanizing antics, and so on. The movie exists on the porous, surrealistic border between dreams and reality, and that hazy tone would continue into Oshii’s subsequent works after he departed Studio Pierrot to make “Angel’s Egg.” (The rest of his staff would go on to make “Project A-ko,” though both films are rooted in “Urusei Yatsura” in their own way, as Brian Ruh argued in his “Stray Dog of Anime: The Work of Mamoru Oshii.”)

As the beginning of a new direction for Oshii, “Beautiful Dreamer” has a reputation for being a departure from the rest of the series — a more philosophical and navel-gazing feature with Rumiko Takahashi’s iconic cast of characters. But “Beautiful Dreamer” does preserve the series’ sense of humor, peppering its introspective plot with winsome moments of absurdity.

-

“Angel’s Egg” (dir. Mamoru Oshii, 1985)

Image Credit: Studio Deen After the wonderful “Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer,” Oshii would leave to then go on to make more idiosyncratic original works, like the 71-minute OVA “Angel’s Egg,” a work some consider to be his best (it also played theatrically, so I’m counting it as a film!). Co-created with artist Yoshitaka Amano, now most famous for his “Final Fantasy” illustrations, “Angel’s Egg” is a work of desolate beauty, set amidst the remains of a war-torn landscape. As Brian Ruh notes in his book, “Angel’s Egg” retains the look and feel of Amano’s typical style, which doesn’t have a “stereotypical “manga” look to it; he eschews pen and ink in favor of a softer watercolor look.” That flowing style feels more than appropriate for the story of “Angel’s Egg,” which is an ultra-ambiguous narrative of of change and rebirth.

The tale is sparse and lyrically told, tracking a nameless young girl as she carries a large orb — maybe an egg! — across a post-apocalyptic wasteland dotted with husks of gothic architecture. It’s so purely symbolic that any means of reading could be projected onto it; it’s an unspeakably gorgeous film that feels like it can keep being discovered forever.

-

“Project A-ko” (dir. Katsuhiko Nishijima, 1986)

Image Credit: Shochiku There’s probably a good third of this list contained within the chaos of Katsuhiko Nishijima’s “Project A-ko,” a gleeful and energetic parody of its ’80s contemporaries from former “Urusei Yatsura” staffers. You name it, there’s probably a joke about it in there somewhere, from the movie’s loving mockery of “Space Pirate Captain Harlock” as a shambling drunkard to its more surreal nods towards “Macross” and “Fist of the North Star,” almost everything made in the ‘80s is thrown into the stew.

And everything is on the table because the driving premise of “Project A-ko” is so unhinged to begin with — a clash of big picture science fiction with high school whimsy. Against an increasingly absurdist backdrop of chaos and property destruction, teenage schoolgirl A-Ko and her boisterous, annoying best friend C-ko dodge alien invasion and the sapphic obsessions of B-ko, a classmate who tries to claim C-ko for herself.

Followed by three sequels that were directed by character designer Yuji Moriyama, “Project A-ko” is mayhem from beginning to end, as it smashes together science-fiction with “Looney Tunes”-flavored high school summer antics, favoring movement and action over reason. Something is moving or crashing or leaping or exploding at every single moment, the story loosely held together by outsized visual gags and exaggerated animation of anything the animators had room to fit in. It skirts the line of good taste —and frequently crosses it — but the good and silly far outweighs the uncomfortable.

-

“Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise” (dir. Hiroyuki Yamaga, 1986)

Image Credit: Toho-Tawa The year before “Akira” came out, another of the most expensive anime productions of its time was also released in the lavishly produced, lavishly titled “Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise.” It’s the debut feature of the now-famous (and now very different, practically defunct) studio Gainax. Directed by Hiroyuki Yamaga, “Royal Space Force” was produced by a fresh-faced staff that would become a who’s who of major artists — with “Evangelion” creator Hideaki Anno acting as animation director, and his collaborator Yoshiyuki Sadamoto handling character design.

The result is beautiful, fantastical spin on “The Right Stuff” told against the backdrop of a vast fictional world where dreams of space flight and pioneering exploration clash with ruthless bureaucracy and even religious belief. A space race is on between the Kingdom of Honnêamise and a bordering Republic, with the lackadaisical Shiro becoming the face of the former’s space program while both states plague each other with espionage and attempts at sabotage. It’s a premise that hits rather classic beats, but they’re no less stirring for that, particularly as they raise difficult questions as to whether space programs are worth the expense when people on the ground are suffering from poverty.

The fictional Oshina republic maintains a sense of rustic tradition in both its costume design and its architecture alike; the space program unfolds amidst wooden houses and huts, while Shiro himself is intertwined with religion through his love interest, Riquinni. Though the characters don’t actually reach the stars during the course of the film — this is more about the dream of space flight rather than the journey itself — the swooning score from the one and only Ryuichi Sakamoto makes it feel as those its characters are already living among them.

-

“Robot Carnival” (dirs. misc, 1987)

Image Credit: Discotek Media The anthology “Robot Carnival” gathers some of the most prolific and talented animation artists of its time period under one loose prompt: your short has gotta have a robot in it. All of that, and it’s bookended by an opening and ending from “Akira” creator Katsuhiro Otomo, who’s in a more cartoonish mood than people typically associate with him.

There’s at least one short for everyone in here. First up is “Franken’s Gears” directed by Koji Morimoto (who has work in other anthologies like “Short Peace” and “The Animatrix,” plus the best short in “Memories”). He kicks things off with a robot-themed spin on Mary Shelley that sees a mad scientist bringing a gigantic skeletal robot to life, its shambling awakening rendered in exquisite detail and wild expressions of color, all of which lead to a grim conclusion.

From there “Robot Carnival” goes in all manner of directions and aesthetic experiments, the anthology a delight for how it continually changes gears. For example, how “Star Light Angel” pivots from the haunting fable of the prior story, “Presence,” to two girls having fun at a robot Disneyland before having their friendship rocked by a love triangle. It’s also an example of how the director’s quirks are so upfront even in the simplest of the stories; directed by “Zeta Gundam” and “Char’s Counterattack” character designer Hiroyuki Kitazume, that authorship feels evident in how the two-timing boyfriend looks like Char Aznable (sorry, I mean “Quattro Bajeena”). The nine shorts all display a sense of unfettered creative freedom, each holding a radically different style as well as perspective on the prompt, all toying with the possibilities of expression that a “robot” presents.

-

“Patlabor: The Movie” (dir. Mamoru Oshii, 1989)

Image Credit: Shochiku Yes, another Mamoru Oshii film, but take it up with him for directing three all-timers in a single decade. A feature film follow-up on the popular “Patlabor: The Early Days OVA,” “Patlabor: The Movie” — like “Urusei Yatsura” before it — feels like a continuation of those speculative interests.

First created by the collective Headgear (director Mamoru Oshii, manga artist Masami Yûki, mecha designer Yutaka Izubuchi, character designer Akemi Takada, screenwriter Kazunori Itô), “Patlabor” often played like a workplace dramedy with its affable cast of goofballs… only as well as desk work, that workplace involved piloting mechs from time to time. The mechs themselves were called “labors,” the very name emphasizing their natures as tools rather than heroic figures.

Oshii approaches “Patlabor: The Movie” as a procedural, one in which budget cuts have a bigger footprint than the mechs, and its officers are determined to solve the fault in their operating system responsible for building a structure of biblical scale (if the meaning wasn’t clear enough, it’s also called Babel). “Patlabor: The Movie” moves with the rhythm of a murder mystery, the events of the film set off by the suicide of an engineer on the massive Babylon Project construction site.

Fortunately, the film’s focus on the politics and existential implications of of technological development doesn’t come at the expense of good-old mech action, and there’s pleasing tactility in the depiction of the labors’ movements. One moment I come always back to finds one of the mechs running out bullets in its gigantic revolver, which cues Oshii to show the pilot climbing out of the cockpit to manually reload each gigantic bullet, one at a time. So, it’s not all paperwork.