A true-life American tragedy that leverages the summery Texas idyll of “Dazed & Confused” into a larger than life — but heartbreakingly sincere — re-telling of “King Lear,” “The Iron Claw” is a wrestling epic inspired by a legend so sad that writer-director Sean Durkin felt like he had to sand it down in order for it to seem believable on screen. Inverting the fake it so real ethos of a sport that’s long been enjoyed as a form of steroidal theater (its operatic melodrama sustained by the exaggerated nature of its spectacle and vice-versa), Durkin’s film dials back the body count so that the scale of its loss doesn’t make it impossible for audiences to accept that it actually happened, or to exalt in the love that it ultimately left behind.

Scholars of wrestling’s pre-WWF history might see “The Iron Claw” as an act of erasure, but I can’t help but feel as if Durkin’s choice to streamline the Von Erich family saga befits the ecstasy of a sport where the line between truth and fiction is body-slammed from the top rope a dozen times every match. It certainly plays into the powerful kayfabe of a movie about four brothers — there were five in real life, or six if you really want to pour salt in the wound — whose father conditioned them to be so focused on winning that they couldn’t see how he rigged their biggest fights against them.

Besides, just as a “fake” wrestling punch could probably knock you unconscious, even this “watered down” story about the curse that Fritz Von Erich passed down to his sons like a self-fulfilling prophecy is still powerful enough to pile-drive you with the force of a WWE World Champion. You can call it “‘The Virgin Suicides’ for boys,” you can call it “Louisa May Alcott’s ‘Little He-Men,’” you can even call it an insult to Chris Von Erich’s memory if you want. However you choose to think of it, “The Iron Claw” deserves at least one title that simply cannot be contested: This is the heavyweight tear-jerker of the year.

That might sound like an unexpected pivot — or maybe even a heel turn — for a filmmaker whose previous features (“Martha Marcy May Marlene” and “The Nest”) were pointedly missing any traces of sentimentality, but “The Iron Claw” is choked by Durkin’s usual tension from the moment it starts. And when its rivers of repressed feeling eventually start to overflow some two hours later, they do so in a spirit of cathartic defiance against the man who dammed them all in the first place. The emotional release earned by the end of this movie isn’t easy or manipulative, it’s an expert reversal worthy of the wrestler who pulls it off; a last-minute escape from the deathlock of Fritz Von Erich’s signature move.

When we meet Fritz (born Jack Barton Adkisson) for the first time in the early 1960s, he’s already living in the grip of his own grief, and it only takes a few clenched lines for Holt McCallany to establish his character as a first-ballot inductee into the Bad Movie Dad Hall of Fame. Forever mourning the death of his first-born son in a freak accident, Fritz turns to his wife Doris (Maura Tierney) and their pre-teen boys Kevin and Kerry in a desolate parking lot after his latest match and repeats a mantra they’ve probably heard 1,000 times: “I will be the world champion and nothing will hurt us again.” The fastest. The toughest. The strongest. The most successful. Pec muscles thick enough to stop a bullet at point-blank range; lats big enough to lift the yoke of life’s greatest heartache. Masculinity as the solution to all suffering. Winning as the absolution of all loss.

“It’s the only way to beat this thing,” Fritz growls at his family in the mission-obsessed monotone that never wavers at any point in the film (McCallany’s performance denies Fritz even the slightest chink in his armor, even when just a single moment of vulnerability might have saved lives in the end or given this movie some more room to breathe). He doesn’t specify what “thing” he’s talking about, but everyone must suspect that it’s death. Maybe that’s why Doris never watches any of her boys wrestle: not because she can’t bear the sight of them getting hurt, but rather because it hurts her too much to see them lose the same fight over and over. Or maybe aversion proves contagious in any family where the person hurting most decides to live in denial of their pain. When one of Doris’ sons tells her that he needs to talk to her about something, she thoughtlessly replies, “That’s what your brothers are for.”

When the movie jumps ahead to the mid-’70s after that brief prologue, we learn a lot more about what the Von Erich clan does and doesn’t talk about. They don’t talk about the kid who died, or the “curse” that would later be used to explain why he did (a photo of six-year-old Jack Jr. is crudely wedged into the side of the family portrait). They also don’t talk about the fact that the youngest of the Von Erich boys included in the film is an artistic soul who clearly wasn’t built to be groomed into his father’s wrestling dynasty. But then again, they don’t really have to, because they do talk about which of the boys is daddy’s favorite; Fritz sits at the kitchen table and ranks them aloud as if he were reading statistics in the sports pages.

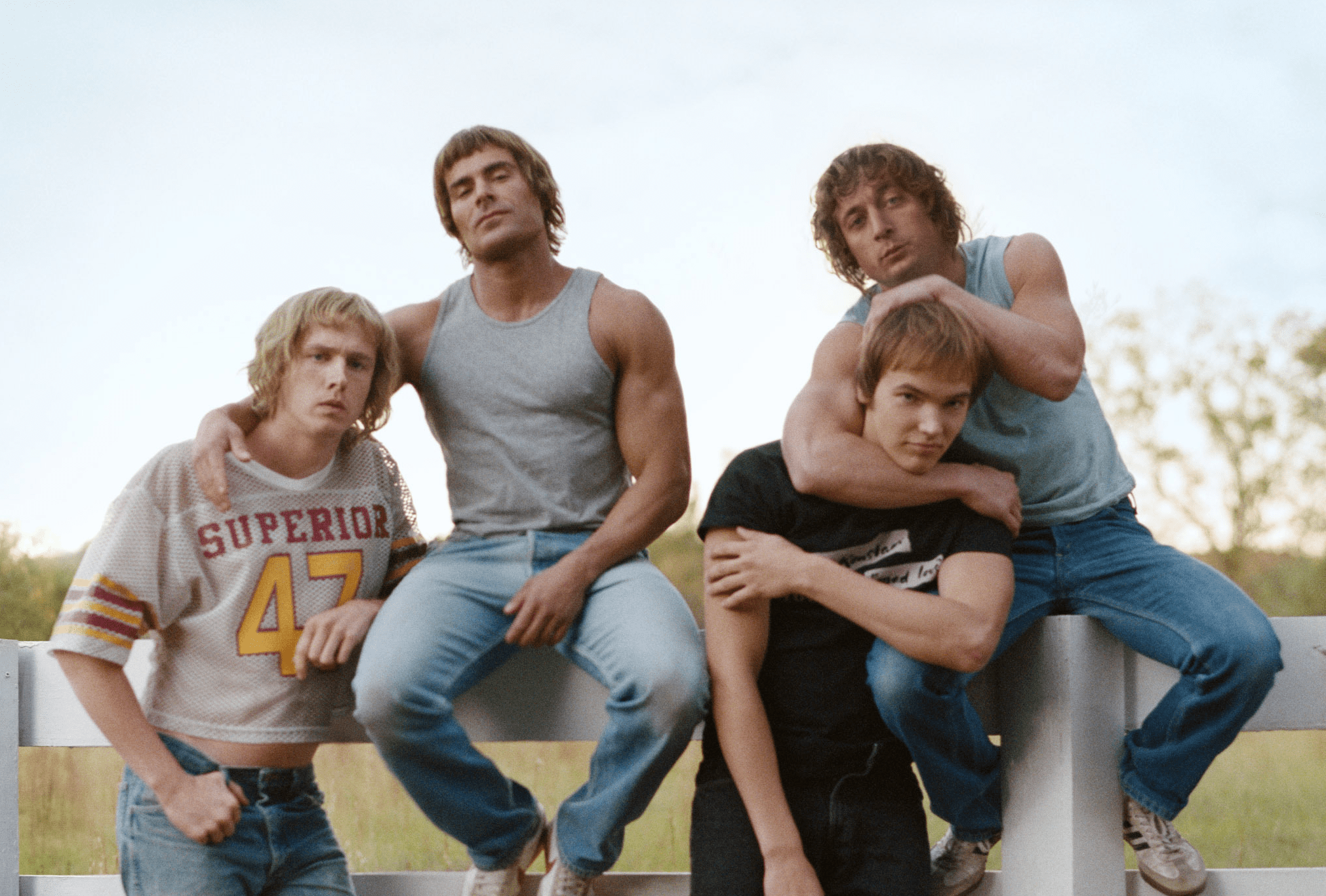

In first place we have the shaggy-haired Kerry (a tortured and perfectly textured Jeremy Allen White), an Olympian-in-training whose “sir, yes, sir!” attitude is offset by his all-American fearlessness. Next is Kevin (Zac Efron, unforgettable as the heart and soul of a movie that’s overflowing with both), the gentle-natured golden boy whose bulging muscles and little kid wearing a stuffed bodybuilder costume for Halloween physique belie the fact that his dad hasn’t allowed him to grow up — I have never been less surprised to learn that an adult film character is a virgin.

After that we have David (the endlessly surprising Harris Dickinson, warm and brilliant as the Linklater-like brother whose skills on the mic soon elevate him to the top of the charts). And then there’s Mike, who’s in last place because he’s built like an indie rocker and just wants to play guitar in his friends’ garage. Literally roped into the family business by a father who refuses to acknowledge that one of his kids broke the mold, Mike is the most readily identifiable victim of the lot, and relative newcomer Stanley Simons embodies him with a go along to get along innocence that proves even more crushing than you might imagine (with a major assist from a resoundingly anthemic original song by Richard Reed Perry, Little Scream, and the Barr Brothers).

Durkin gives Mike short shrift compared to the rest of its characters, but so does his dad. His siblings, however, clearly love him and each other to the moon and back in spite of the competition that Fritz has bred into them, and that — more than anything else — is what gives the Von Erich boys their strength. Well, that and the constant working out instead of having fun and/or sex. It’s also what gives “The Iron Claw” its immense depth of feeling. Weighing in at a combined weight of 690 lbs. (even before Mike is added to the mix), the Von Erich brothers are a natural born tag-team who give each other the space and affection their father has always withheld from them — a fact that Fritz and Doris both seem to appreciate. They’re happy to fight each other’s battles with and for them, even as they’re all being reduced to cannon fodder in their father’s war against the world.

Durkin’s movie has its fair share of crucial moments in the ring, but none of them would land with a fraction of the same impact if not for the many crystalline little moments in which Kerry, Kevin, David, and Mike get to build each other up. The first half of the film — before the cataclysm begins — is rife with sun-dappled glimpses of these golden-haired gods just vibing on being able to call each other “brother” as Mátyás Erdély’s cinematography drinks in the ambrosia of an eternal Texan summer (“The Iron Claw” thrives on the semi-mystical sense of place that it’s able to forge from its Louisiana sets, an alchemy it owes to flawless re-creations of relics like the Dallas Sportatorium and Ric Flair. OH THAT’S RIGHT, RIC FLAIR. YOU BETTER PRAY CARSHIELD WILL COVER THE BEAT-DOWN THIS 145 LB. FILM CRITIC IS ABOUT TO PUT ON YOU). There’s a scene where the boys help Mike sneak out of the house so his band can play a gig at a local college, and the shot of Kerry and David beaming with pride as they watch their brother rock out in his element is so palpably full of love it’s like they’re all going to live that way forever.

And if that doesn’t break your heart, there are any number of other bits that might. Kevin, who’s only absent from Mike’s show because he’s too busy flirting with his future wife (Lily James, making the most of a thankless role), is front and center for most of them, and Efron’s devastatingly guileless performance seems to find a new stratum of sadness with each beat. The disgust that flashes across the actor’s face after Kevin catches himself being jealous of David’s success is only visible for a millisecond, but it reflects a lifetime of keeping inherited demons at bay.

For all of Efron’s muscles (and there are so, so many of them), this is where he locates his character’s true strength — the strength of a man whose moral clarity is obscured by his misguided sense of purpose. Kevin is the most committed man on planet Earth, and yet he doesn’t have the first clue about why he’s trying to become World Champion, or what’s truly in his way. “How does that happen?,” he asks his father when tragedy strikes, blithely unaware that he’s staring at the answer.

“The Iron Claw” occasionally struggles to maintain its pace once the pain starts to come in cascading waves of tragedy (even without Chris Von Erich, it can seem as if Durkin is rushing to keep up with all of the awfulness that befalls his characters), but the film recovers its footing whenever it returns to the erosion written across Efron’s face as Kevin finds the strength to confront the same pain that his father never could. It’s a process that culminates in four or five consecutive scenes of overwhelming power, some as subtle as a tightening of Efron’s fingers, others so obvious they would seem cheesy if not for how well Durkin’s film has earned them.

Fritz Von Erich wouldn’t let his kids show their emotions at their brothers’ funerals. He always told them that a man doesn’t cry. In the end, Fritz was a stock villain in a story full of singular heroes, but that doesn’t change the fact of how satisfying it is to watch “The Iron Claw” prove him wrong — on both sides of the screen.

Grade: B+

A24 will release “The Iron Claw” in theaters on Friday, December 22.