Almost every woman has a story: A stranger who followed her through a parking garage. A cab driver who asked uncomfortably personal questions. A date who became frighteningly obsessive. A friend who wouldn’t take no for an answer. The frightening banality of these events is the engine that drives “Woman of the Hour,” the directorial debut from actress Anna Kendrick.

Based on the true story of serial killer Rodney Alcala — who was convicted in 1980 for the murders of seven women and girls, but is suspected of killing more than 100 — “Woman of the Hour” is a more mainstream study of the tension between heterosexual desire and implied violence also evoked in Jane Campion’s “In the Cut.” Unlike that film, however, “Woman of the Hour” leaves the erotics of this dilemma unexplored from the female point of view. The women in this film are not trying to square their attraction to men with their fear of them. They simply want to make it home alive.

The film is shallower than it could be as a result, an issue that largely comes down to Ian MacAllister McDonald’s unfocused screenplay. We open with a title card reading “Wyoming, 1977,” and a young woman pouring her heart out about a recent breakup to a long-haired young man she’s just met. Rodney Alcala (Daniel Zovatto) lured this girl to a remote mountain location with the promise of shooting her for a photography contest. She’s vulnerable. He’s predatory. What happens next is depressingly predictable.

That’s the first of a handful of storylines that make up the film. Some of them overlap, and some do not. Each focuses on a different woman who had the misfortune of crossing paths with Alcala. They vary in length, location, year, and substance, and the timeline jumps around in ways that sabotage the film’s momentum. The least effective of these subplots features Nicolette Robinson as a woman whose attempts to report Alcala to the police go unheard; she’s a clear narrative contrivance, there to make a point and then exit the story.

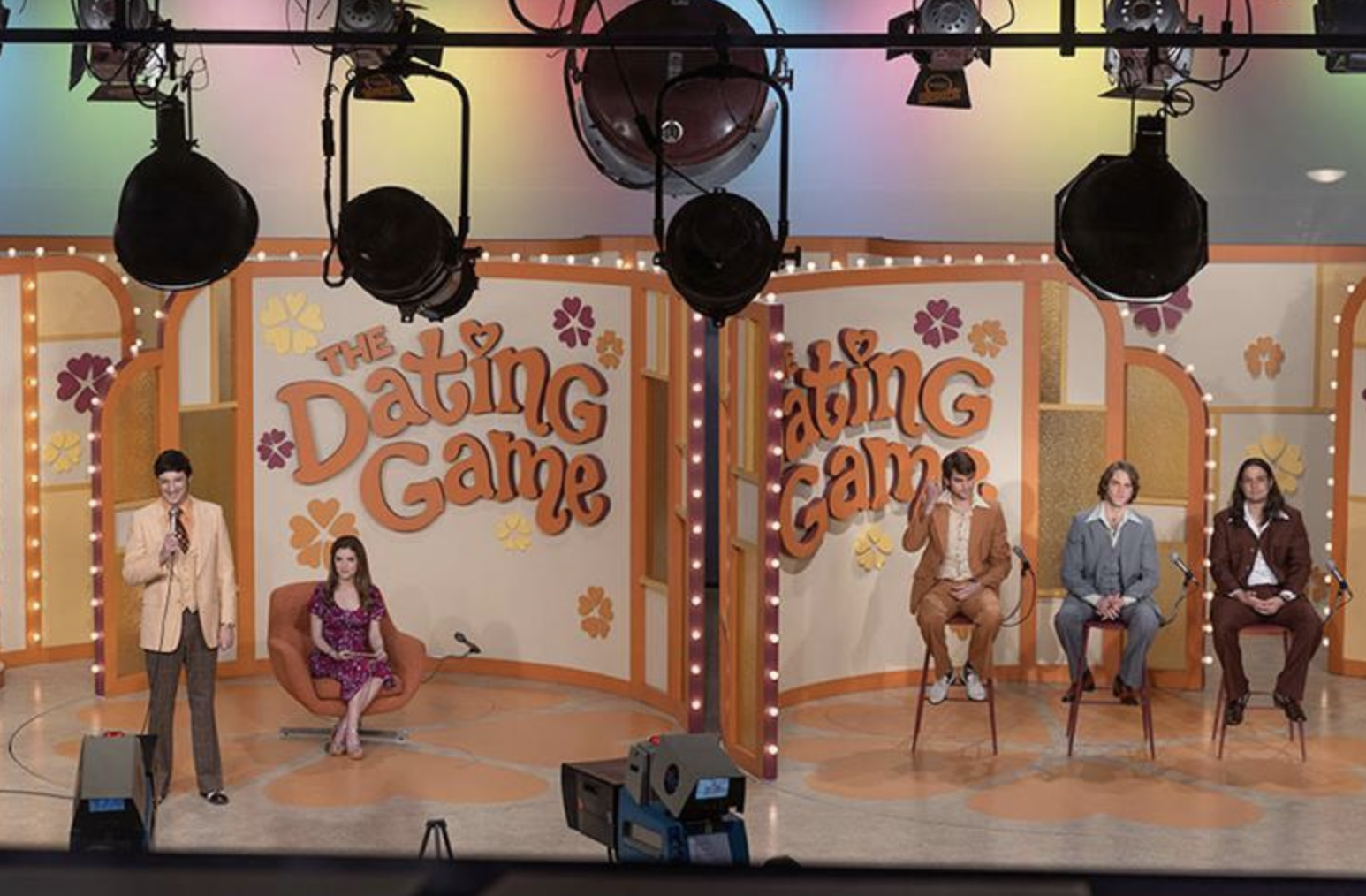

The most effective gives the film its title, tracing a close call between aspiring actress Cheryl Bradshaw (Kendrick) and Alcala when the two of them matched on “The Dating Game” in 1978. Cheryl is on the verge of giving up on her Hollywood dream: Casting agents casually degrade her within earshot, and her only friend in L.A. (Pete Holmes) is one of those guys who thinks he’s owed something simply for being nice. Then her agent suggests that she could go on the TV show “The Dating Game” — you know, for exposure.

This is a relatively low-budget film, which means that the ‘70s period settings are held together largely by costuming and set decoration. (Think shag carpeting and tan leather.) It’s all convincing enough that references to films of the era like “Rosemary’s Baby” and “The Panic in Needle Park” aren’t really necessary, and stand out in a bad way. This is another weakness of McDonald’s screenplay, whose bluntness pays mixed dividends. The performances are subtle by comparison, and Kendrick and Zovatto are especially good together; when he brushes her hair behind her ear, the small gesture comes laden with sinister meaning.

Kendrick’s image as an actor isn’t necessarily tied to dark, edgy material, but as a director she shows a talent for staging scenes of Hitchcockian suspense alongside her signature wit. Amid the heap of disjointed elements lies a pair of knockout bravura sequences, both of which revolve around Cheryl’s appearance on “The Dating Game.” First comes the wit, as Cheryl goes rogue with her on-air questions to spite the show’s chauvinistic host (Tony Hale). Then comes the suspense as Rodney pursues Cheryl through an empty parking lot, following her just close enough to deny his true intentions.

Kendrick’s evocation of the type of fear a woman feels when a man suddenly shifts from friendly to hostile comes through strongly and clearly, and seems destined to spark conversations about similar events in viewers’ lives on the way out of the theater. Beyond that potent impression, what “Woman of the Hour” is trying to say about gendered violence remains obscure until the very end, when the story of a teenage hitchhiker who escaped Alcala in 1979 gives the movie its thesis statement. “It’s okay, baby,” she says with a smile, bruised and bloody after a brutal attack. She plays along, so she survives. And the game goes on, as it has forever.

Grade: B-

“Woman of the Hour” premiered at the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival. It is currently seeking U.S. distribution.