Editor’s note: This review was originally published at the 2023 Busan Film Festival. Netflix releases the film on its streaming platform on Friday, October 27.

Paradise is ever elusive in the work of Bong Joon Ho, no matter what form it might take. That’s true whether it be resolution in “Memories of Murder,” wealth for the Park family of “Parasite,” or even the so-called “calm” that dead animals bring in “Barking Dogs Never Bite.” It’s this search for happiness that typifies the South Korean auteur’s work best, and nowhere is that more evident than in director Bong’s first narrative film: “Looking for Paradise.”

It’s often presumed that “White Man” — a 16mm short released in 1994 — was Bong’s directorial debut, but Netflix’s upcoming documentary, “Yellow Door: ’90s Lo-fi Film Club,” reveals that’s not the case. “Paradise” actually predates it by two entire years and, looking back now, it’s clear that Bong’s stop-motion debut is the more important film of the two, as it laid the groundwork for everything he’s created in the three decades that followed.

Yet strangely enough, “Paradise” remains a mystery to everyone except the members of Yellow Door, a cinephile collective who gathered on Christmas 1992 to celebrate Bong’s work at the film’s one and only public screening. Even now, some of them are confused by what they actually saw.

“Yellow Door” begins with a muddled recollection of “Paradise” that mixes up who the protagonist is and even where it was shot. So starts a delightful journey into the past, where various Yellow Door members reunite to piece together the truth behind Bong’s first film, “Rashomon”-style. But director Lee Hyuk-rae, a former member himself, isn’t just concerned with that. Bong’s early beginnings are mirrored by the formation of Yellow Door itself, which “came together like a cloud of dust,” or “ripening grapes.”

Back in ’90s Seoul, Jong-tae Choi spearheaded the group’s mission to obtain arthouse films they could analyse on VHS. Classic gems were hidden among the wares of illegal street vendors, and Bong, who was in charge of cataloging each treasure they collected, had a particular knack for finding them. Five hundred tapes later, Yellow Door created their first magazine in the spring 1993, which helped establish them as a distinctive voice within Korea’s growing surge of cinephile collectives.

Watching “Yellow Door,” it’s clear that Bong wasn’t the only talented member of the group. Following his work on “Sewing Sisters,” a documentary about Korean labor that moved Park Chan-wook to tears, Lee Hyuk-rae makes creative use of form and space here to bring the origins of Yellow Door to life. Each interview is shot using dynamic angles and animation features throughout too, often in homage to Bong’s debut. The building where Yellow Door was based is even drawn on screen at one point, directly transporting us back into the past. Snappy edits also ease us in with humor as various chats hilariously contradict each other, but with a kind familiarity that could only come from someone who himself holds a personal relationship with everyone involved.

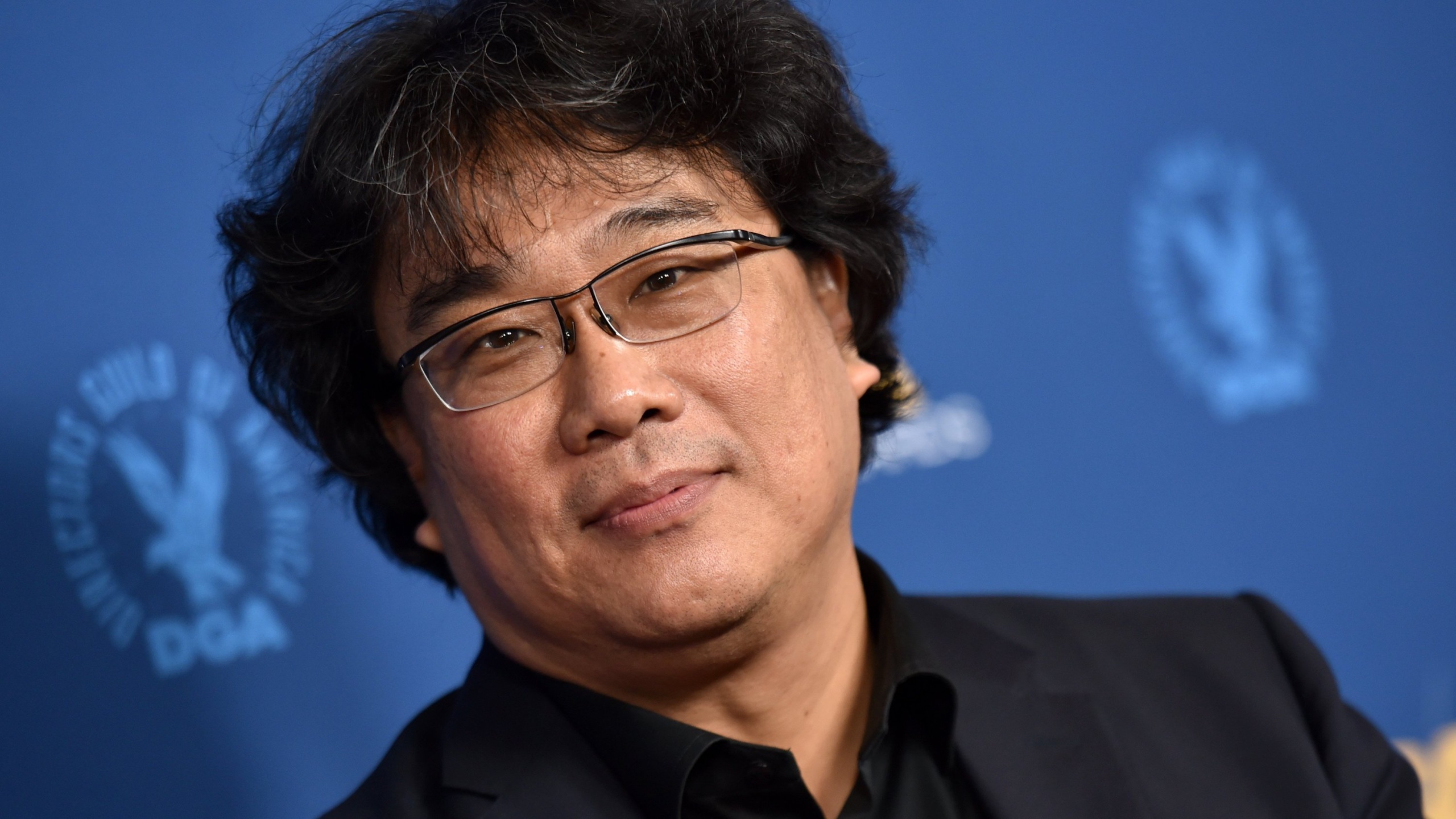

It’s to the doc’s credit that “Yellow Door” isn’t just about Bong Joon Ho, because there are plenty of other interesting personalities in the mix too, many of whom sadly gave up on their passion for film after the group disbanded. Still, their joy in participating here is palpable, making you feel like you’re a part of the gang, and that’s why Bong seems more comfortable than perhaps ever before on screen. He’s among old friends, looking back at their shared past together with a smile, a grin, and even a gentle tear.

Yet even with this degree of familiarity, a younger Bong was still nervous for the others to see “Looking for Paradise” when he first revealed it to them in 1992. “I turned red up to my ears,” remembers Bong, and he does so again in the present when his film’s outlandish plot is described in full.

Shot over two days, “Paradise” follows a gorilla who’s trying to escape a basement, “To get to a place without monsters,” as Bong puts it. But monsters are already there, just not how you’d expect. When the gorilla defecates on a stone (with grunts voiced by Bong himself), his poop transforms into a worm, which is white, not brown, because that would have been “too gross.” The worm then attacks its maker, but the gorilla survives and climbs up out of the basement using pipes overhead.

At the end, our hero makes it to a beautiful tree that stands alone in a gorgeous field. Paradise, at last. Except, this being a Bong Joon Ho film, paradise is fleeting, because the camera tracks back then, pulling out away from the tree until we’re suddenly back in the real world, watching the gorilla see all this play out on a TV before him. If paradise is to be found here, it’s more about the mental release that comes through losing yourself in a screen rather than anything physical.

This twist is rather fitting for someone as passionate about film as Bong is, although making the short tested even his love of movies by the end. Bong reveals in “Yellow Door” that he decided to give up on animation after making “Paradise” because he was tired of moving the gorilla frame-by-frame for that stop-motion effect. “I like it when the actors can move themselves,” jokes Bong in the doc. But even when he turned to live-action soon after, “Paradise” clearly stuck with him still.

“Yellow Door” makes a point of this by placing similar basement shots side-by-side from across Bong’s filmography, reminding us that he never really escaped from that location either, just like his first protagonist. This very specific sense of place has become a key signifier of Bong’s work, especially in “Snowpiercer” and “Parasite,” where his fascination with class inequality is made tangible through physical separation, be it through connecting train carriages or the floors of a fancy house. Like the marginalized characters in those movies, the gorilla from “Paradise” is forced to look up as he dreams of something better.

This sympathy towards strange animals is echoed later in the way Bong portrayed Okja in Netflix’s sci-fi fantasy of the same name, and even the creature in “The Host” is a victim of circumstance, mutated into something monstrous by those in power. Through the suffering of these poor beasts, the cruelty of man becomes all-too apparent.

Yet there’s humor too, especially when the “Paradise” gorilla defeats his poop worm nemesis. Such comic absurdity can be found in everything Bong has made since, albeit in a more refined manner. For example, “Mother” takes great delight in making us laugh even as horrific events unfold, and “Memories of Murder” also finds humor amidst suffering, especially in that first hour.

But still, nothing quite compares to the arrival of that worm.

Then there’s the stone that poop was “birthed” on in the first place. Rocks recur regularly throughout Bong’s worldview, be it the “Suseok” stone from “Parasite” or the murder weapon in “Mother.” Who knew this all started with some sausage-shaped white clay in his mother’s basement? Thanks to “Yellow Door,” now we do.

Toward the end of the documentary, Bong tells us, “I don’t think I’ve ever been as passionate about film as I was making ‘Paradise.’” Knowing how much that short impacted what came next, you could argue Bong might be trying to recapture that earlier passion by channeling elements of “Paradise” into every new project, whether he’s doing so consciously or not.

But as Bong himself has taught us, paradise is an elusive notion. Thankfully, there’s still plenty of passion to enjoy in the nostalgic joy that “Yellow Door” brings, both to him and to us.

Grade: A

“Yellow Door: ’90s Lo-fi Film Club” premiered at the 2023 Busan International Film Festival. Netflix will release the film internationally on Friday, October 27.