Editor’s note: This review was originally published at the 2022 Tribeca Film Festival. Cargo Film and Releasing releases the film in select theaters on Friday, June 2.

On the land and in the water, the whispers of a people, their descendants, and their hereafter echoes, from the first words spoken when enslaved Africans arrived on the shores of America to their continued cries throughout the Civil War. And when, on the eve of January 12, 1865, twenty Black ministers met with General William Tecumseh Sherman in Savannah, Georgia to plot out the reconstructive future of newly freed Black folks, the promise of forty acres and a mule seemed to guarantee prosperity, and perhaps some sort of answer.

And yet, the tragedy of that night is a dream that was deferred. The formerly enslaved would ultimately gain land: parcels not given to them, but purchased in the decades following the Civil War. Amid the arched mossy trees, the sweaty swamps and islands formed by vascular waters, new communities took root. They fished, and they tilled under the cloud of Jim Crow. But most of all, they heard the whispers of the past, both the good and the bad.

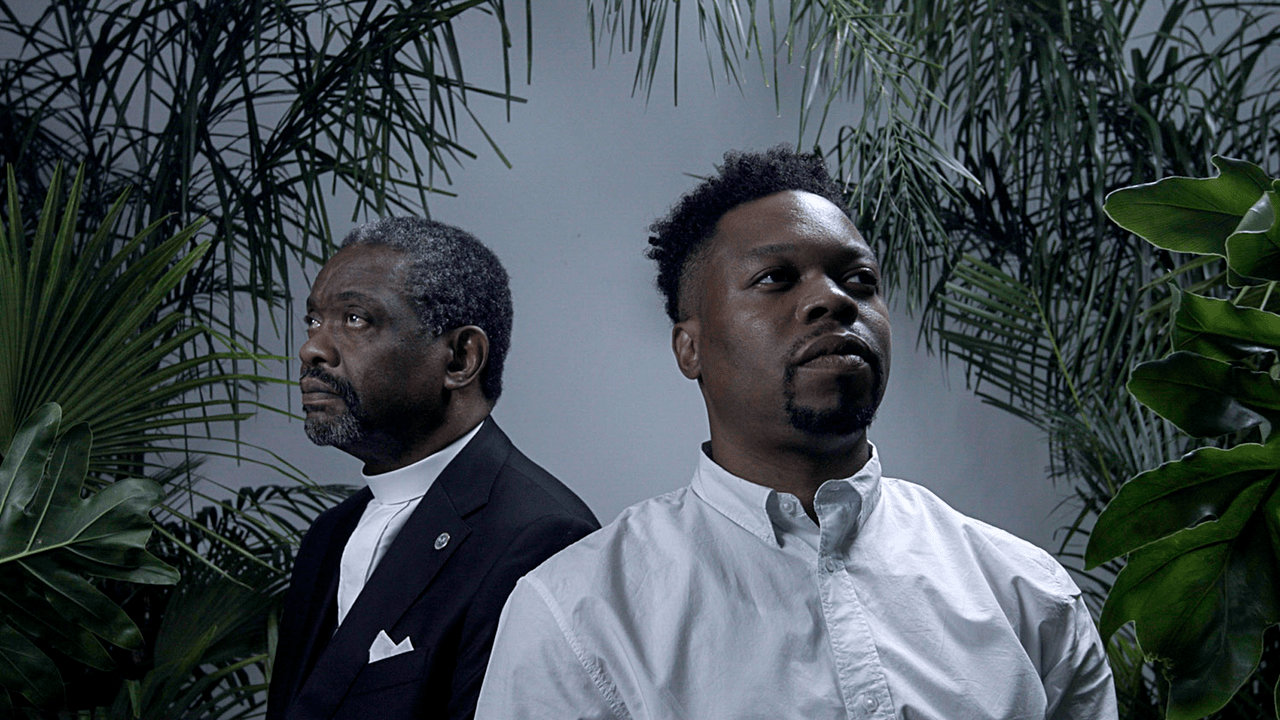

In the lush documentary “After Sherman,” a piercing personal essay by Jon-Sesrie Goff, the director patches through time by speaking with his father, friends, and neighbors to tell the history of the Gullah Geechee community. It’s a meditative work, a film that can often descend down rabbit holes without a clear path out, but whose explorations unearth far more than it leaves buried.

“There is a birthplace and there is a home place,” explains Goff’s father, the Reverend Norvel Goff Sr. The subtle yet poignant difference between the two locales instigates the friction of this cinematic journey. We are where we’ve come from, but we become where we choose. Still, no matter where we go, the place we call home is always influenced by our past. Hailing from Connecticut, the director is wistful for his father’s birthplace in South Carolina, where the younger Goff often spent his summers. Despite arriving in the north decades later, Goff is a product of the Great Migration’s legacy. Similar to those Black folks, he’s trying to define what home means as he lives in 150-year old wake of slavery, a practice that violently ripped Black folks from their birthplaces and families.

That excavation begins in the camera’s relationship with the land. “After Sherman” isn’t a documentary composed of bland, sweeping drone shots of the Southern terrain. The lens hugs the long grass, the furrows of mud and the deep, murky water with warmth of kinfolk. The area has fed Goff’s people, it’s housed their caskets, and has offered places of worship and celebration. A tapestry of home videos and stunning black and white footage recalls church services and household gatherings. Footage of a ’50s high school football game, in particular, is joyous and haunting, as editor Blair McClendon juxtaposes the gleeful crowds and cheerleaders to a former player recounting a post-game warning of the KKK meeting in a nearby cemetery. The way Goff deploys these archival images bears reminders of Zora Neale Hurston’s “Fieldworks” without the anthropological ends.

Goff mixes these snapshots with present-day reflections: portrait stagings of Black families, a rapturous parade, and conversations between young adult African Americans concerning the difference between living in big Northern cities like New York or in smaller Southern towns. These are cheerful gatherings, with an underlying importance to them. Is, as Malcolm X once said, “the South any place below the Canadian border”? The question hangs over every smile like an urgent pang, especially as property taxes increase in South Carolina and the Gullah Geechee community is forced to sell their generational land to rich, white property owners or as racial violence hits close to home.

The director’s father is the presiding elder of Mother Emanuel Church where, in 2017, white gunman Dylann Roof murdered nine Black churchgoers. While looking back at the event, “After Sherman” becomes less of a free-wheeling contemplation punctuated by stop-motion animation and double- and triple-tracked narrations by multiple subjects, but more conventional in its storytelling. The tragedy at Mother Emanuel Church and his father’s near-death experience is powerful, and the present-day ramifications with regards to racism are disturbing — and yet, those emotions are somewhat guarded by the strict form. The same can be said of the director’s adherence to chapter titles, which only seem to break the film’s spell rather than enhance it.

Instead, “After Sherman” works strongest when Goff allows his broader interrogations to run visually and narratively free. The film fascinates whenever the director poses big questions, with even larger implications to his father, such as what his dad hoped the world would be for his son. It uplifts whenever the symphonic poetry of the South’s accents makes an appealing sonic texture. And the documentary finds peace and frustration when it becomes wholly concerns a community’s relationship with the land and its history.

In a piece filled with a variety of indelible images, the sight of a local Black woman, hoping to retain parcels of her community’s birthplace and being out bid at a public auction by richer entities, encapsulates the dream and the reality of Sherman’s promise. It also explains why Goff’s “After Sherman” nourishes both the spirit and soul.

Grade: B+

“After Sherman” premiered at the 2022 Tribeca Film Festival.