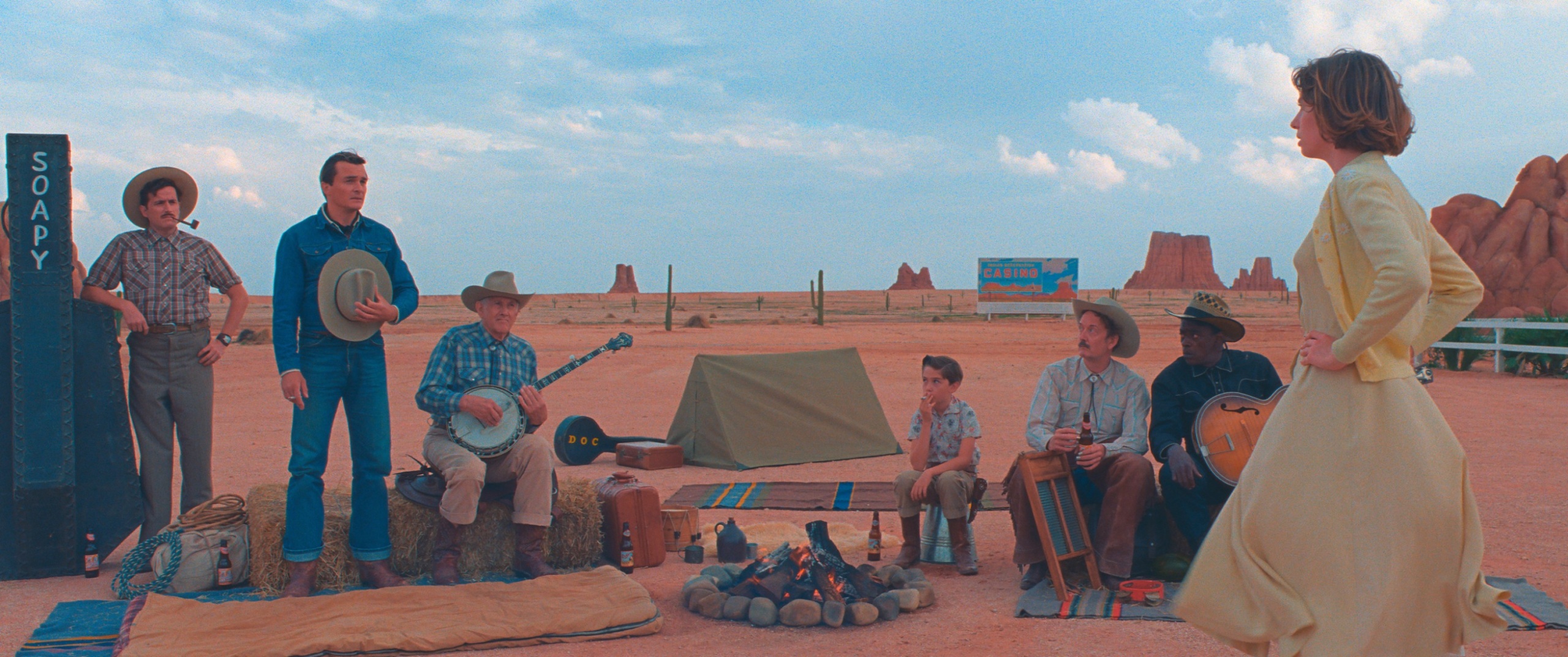

In Wes Anderson‘s “Asteroid City,” a group of scientists, military personnel, and “Junior Stargazer” science students gather at a giant meteor crater for a ceremony honoring the kids’ inventions, only to see the celebration take an unexpected turn when an alien arrives. Although the story takes place in 1955 and deals with science fiction elements and then-futuristic technology, the methods used to bring Anderson’s world to life are drawn from even farther back in cinema history. “It was kind of going back to what the early pioneers of film did,” cinematographer Robert Yeoman told IndieWire. “They built sets [out in the sunlight] and just put diffusion cloth on top.”

For “Asteroid City,” this approach derived from the fact that Anderson wanted to use all natural light for the scenes in the desert town after which the movie is named. “I knew that inside locations like the diner would need light, so I just asked if we could put skylights in the diner and any building where we knew we were going to be shooting day interiors,” Yeoman said. “[Production designer] Adam Stockhausen put skylights in and we covered them with very soft diffusion material and it worked out beautifully. We never used any lights, and that was Wes’ dream.”

Shooting in natural light was in keeping with Anderson’s simplified, lo-fi approach. “He likes to keep the set as small as possible,” Yeoman said. “I’ve worked on big studio movies where you look around and there are hundreds of people standing around and five video villages and it’s just a giant apparatus, but Wes likes to move fast and does not believe in any of that stuff. It’s often just him, myself operating, a focus puller, a second AC with a slate, a dolly grip and a boom guy, and that’s it. Wes has a little monitor that he holds and he sits next to the dolly, but he watches the actors. He just checks the monitor because if I’m making a move, he wants to see the move. In his dream world, he would have eight people making the entire movie.”

Anderson’s desire to strip things down and focus on the actors informed Yeoman’s approach to another environment in “Asteroid City,” the milieu of 1950s live theater in which actors are ostensibly staging the alien story as a play within the movie. For these black-and-white, Elia Kazan-inspired sequences shot in the Academy ratio (as opposed to the sci-fi story’s color and widescreen), Yeoman and his camera department pre-lit everything so that when Anderson and his actors stepped on the set they “just flicked the lights on.”

Looking to Francis Ford Coppola and Vittorio Storaro’s work on “One From the Heart” as an influence, Yeoman allowed himself to have fun with the New York theater world, creating expressionistic lighting changes within scenes that contrasted with the more straightforward natural light of the desert passages. “I love the idea of lights changing within a shot and coordinating those moves to the actors,” Yeoman said. “We do a lot of dimming, or a spotlight might come on someone, and it’s a very theatrical way of shooting.”

Yeoman had far less control in the desert, and it was a constant challenge maintaining consistent light in the movie’s many day exteriors. “On other movies, I would be tempted to bring in some big lifts and put giant silks up to soften the light, but it was too windy out there in the desert,” Yeoman said. “It would’ve been dangerous. But also, Wes was really eager to embrace harsh sunlight. We looked at some movies together, like ‘Bad Day at Black Rock’ and ‘Paris, Texas,’ and they were not afraid to shoot at high noon so that the light becomes kind of a character in the film. We rarely used anything other than a bounce card to put some light in the actors’ eyes. It goes against all of my past as a cinematographer, where you always want to soften or shape the light in some way, but eventually, I embraced that approach.”

Beyond the lighting, Yeoman was faced with his usual challenge on a Wes Anderson film: executing the director’s extremely complicated and precise camera moves, which have become increasingly ambitious. It’s not unusual in an Anderson movie for the camera to make several 90-degree pivots in a shot combined with dolly moves and swish pans, all of which have to be meticulously coordinated with the director’s penchant for deep-focus, symmetrical compositions.

For Yeoman, the planning begins in pre-production, when he walks the location with a viewfinder to see if the shots in Anderson’s animatics are physically possible. In the case of “Asteroid City,” Stockhausen built an entire desert town in forced perspective on the outskirts of Chinchón in Spain, and the placement of buildings was slightly adjusted to make sure the actors and camera could get from one point to another in the time allotted by Anderson’s dialogue. “If the dialogue takes place in a minute, we need to make that shot within a minute, not a minute 10,” Yeoman said.

During production, the camera moves are accomplished via a system created by key grip Sanjay Sami, with whom Yeoman has worked since “The Darjeeling Limited” in 2007. “He has dolly tracks that go back and forth and sideways that he can switch, like a train,” Yeoman said. “Those tracks have to be tightly controlled because it has to be down to the millimeter. There’s a small crosshair on the camera and Wes can see when you didn’t make it. When you land, it has to be very precise, and it’s so fast you couldn’t use a Steadicam or a Technocrane.” Adding to that is the complication of keeping everything in focus: “It’s very tricky because often Wes will have a character way in the foreground and someone way in the background, and he’ll want them both in focus. So it takes the three of us — Sanjay pushing the dolly, me operating, and Vincent [Scotet] on the focus — to do a really difficult move, and when we can achieve it, I get a great deal of satisfaction.”

Yeoman also gets satisfaction from continuing to shoot on film. “I love digital cameras, don’t get me wrong,” he said. “But I think when you shoot film everyone is much more focused because they know there’s only a finite amount of film in the camera. When I shoot things digitally, often they just keep the camera rolling while the hair and makeup people come running in, and I feel like the attention gets diffused. With film, everyone pays attention more, and Wes likes that focus. This may sound weird, but I think somehow that energy finds its way onto the negative.”