This year’s Cannes has come to an end, but its ripple effects will be felt across the rest of the year, as the the 2023 edition of the ultra-prestigious festival played host to a deep and extraordinary array of premieres from some of the world’s greatest filmmakers, several of whom were debuting new work for the first time in the better part of a decade (or longer).

In most cases, the wait proved worth it. “The Zone of Interest” director Jonathan Glazer stunned the Croisette with his much-anticipated follow-up to 2013’s “Under the Skin,” while the likes of Aki Kaurismäki, Catherine Breillat, Tran Anh Hung, and Martin Scorsese — whose epic “Killers of the Flower Moon” only felt like it was forever in the making — all returned with major triumphs that reminded us of their singular brilliance (apologies to Victor Erice, whose rapturously received but inconveniently scheduled “Close Your Eyes” eluded our team on the ground). Even Cannes mainstays like Hirokazu Kore-eda, Wes Anderson, and Palme d’Or-winner Justine Triet seemed to be reinvigorated and compelled to push themselves further out of their comfort zones than ever before, while newcomers like Camera d’Or-winner Thien An Pham (“Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell) and relatively unheralded talents like Anthony Chen (“The Breaking Ice”) unveiled films that could easily stand shoulder-to-shoulder with those from giants of the medium. There may not have been another “Aftersun,” but there’s no use complaining about that in the wake of a festival that gave us the first “Robot Dreams.”

Here are the 14 best films we saw at Cannes 2023.

This article includes contributions from Siddhant Adlakha, Christian Blauvelt, Ben Croll, Sophie Monks Kaufman, Eric Kohn, and Josh Slater-Williams.

-

“About Dry Grasses” (dir. Nuri Bilge Ceylan)

Image Credit: MUBI At nearly 200 minutes in length, “About Dry Grasses” is par for the course for Turkish virtuoso Nuri Bilge Ceylan. He returns, once again, to the icy frost of his Anatolia-set Palme d’Or winner “Winter Sleep,” for a story that beats with similar frustrations towards power in the grand social scheme. However, he weaves this theme into his background tapestry, favoring instead a talkative and often discomforting tale of a small-town art teacher, his 12-year-old female student, and an accusation of impropriety that might be false on its surface, but is rooted in truths the camera sees.

Where “Winter Sleep” adapted Russian greats like Chekhov and Dostoyevsky — it draws from both “The Wife” and “The Brothers Karamazov”— “About Dry Grasses” plays like a spiritual descendant of Nabokov’s “Lolita,” at least in its use of point-of-view. Ceylan’s novelistic approach to cinema could perhaps find no more fitting a partner than Nabokov’s lyricism, the kind that is at once cinematic in spirit, and yet wholly difficult to adapt for the screen.

Ceylan’s latest takes a similarly imaginative, poetic approach to everything from the dull and mundane to the downright sordid, filtering a distasteful story of a man beset by rural frustrations through a surprisingly personal lens, one that keeps things frequently intriguing, occasionally electric, and altogether challenging. It’s only toward the very end of the movie’s 3 hours and 17 minutes that one feels the weight of its running time, by which point anything approaching emotional oppressiveness becomes added emphasis — an exclamation point at the end of its protagonist’s narcissistic screed. —SA

-

“Anatomy of a Fall” (dir. Justine Triet)

Image Credit: NEON They say trends come in threes. And so, nipping on the heels of Alice Diop’s “Saint Omer” and Cedric Kahn’s Directors’ Fortnight breakout “The Goldman Case,” Justine Triet’s Palme d’Or-winning “Anatomy of a Fall” make a compelling case that the courthouse has become the most fertile ground in contemporary French cinema, offering incisive auteurs both motive and opportunity to put social structures on trial. As it calls the institution of marriage to the stand, Triet’s piercing film holds the ambient tensions and illogical loose ends of domestic life against the harsh and rational light of a legal system that searches for order in chaos.

Rounding out her own impressive hat trick, “Toni Erdmann” and “The Zone of Interest” star Sandra Hüller dazzles in a role clearly written with the performer in mind. She plays Sandra, a German-born, France-based bisexual novelist accused of killing her male partner in a way eerily foretold by one of her novels. And if that description calls to mind another icy-blond (in a performance, incidentally, that also shook the Cannes Film Festival, back in 1992), the echo is both wholly intentional and entirely irrelevant. Indeed, “Anatomy of a Fall” is filled with such anti-portents –coincidences or clues, depending on who you ask, echoes or empty noise, depending on who’s listening.

“Anatomy of a Fall” is never really about the trial that follows; at its searing best, the film tracks the destruction of a family with cold precision. If an artist relies on memories, why not also share nightmares? Why not build a polar vortex that crushes fact under fiction, that lifts from last night’s argument, today’s viewing of a ’90s classic and tomorrow’s worst fears? It’s a cyclone that sends the mind soaring, and primes the heart for a hefty fall. —BC

-

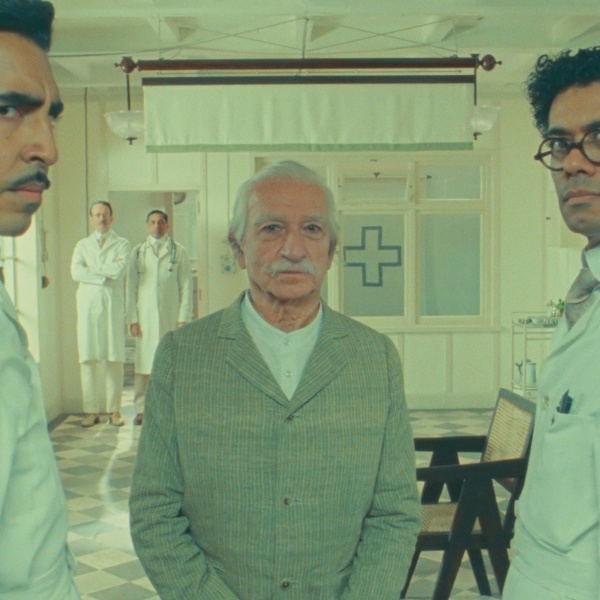

“Asteroid City” (dir. Wes Anderson)

Image Credit: Focus Features Like any movie by Wes Anderson, “Asteroid City” is the epitome of a Wes Anderson movie. A film about a television program about a play within a play “about infinity and I don’t know what else” (as one character describes it), this delightfully profound desert charmer about a group of people trapped in a tiny Southwestern outpost during a 1955 science convention — by far the director’s best effort since “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” and in some respects the most poignant thing he’s ever made — boasts all of his usual hallmarks and then some.

As expected, the world of “Asteroid City” is meticulously arranged with clockwork precision, and — as expected — that world is then populated with memorable characters who try to assert the same degree of control over their own lives. So far, so typical. But then, in one brilliant stroke, what seems like just another immaculate Wes Anderson movie suddenly becomes one of a kind, as “Asteroid City” spins in a cosmic new direction that forces all of its characters to abandon their delusions of authority. It’s maybe the most radical thing that has ever happened in one of his movies — the sort of transformative moment that A.I. could never dream up no matter how much data it ingested — and it tees up a dreamlike and profoundly moving story that finds something beautiful about surrendering to the great unknown. —DE

-

“The Breaking Ice” (dir. Anthony Chen)

Image Credit: The Breaking Ice A sweet and shimmeringly beautiful sad hot people film about how life can flow and then freeze and then thaw into something entirely new if you let it, Anthony Chen’s “The Breaking Ice” finds hope in the most frigid of places. In this case, that place is the small Chinese border city of Yanji during the depths of its endless winter, when people’s breath is as thick as the gray fumes that spew out of the factory smokestacks, and the snowy peak of Changbai Mountain looks closer to heaven than it does to Pyongyang.

It’s there, against the most inhospitable of backdrops, that a love triangle of sorts will form between a prickly tour guide (Zhou Dongyu), a rangy local (Qu Chuxiao), and a suicidal rich boy who’s visiting from Shanghai (Liu Haoran). The Singaporean Chen is something of an outsider to this story himself, and he brings a palpable sense of passing through to a film in which spiritual freedom rubs up against purgatorial immobility. It’s amazing how fast youth can fester when it’s fenced in or denied its future, and “The Breaking Ice” percolates with the leftover energy of people whose collective life force simply won’t let them lie flat and give up. —DE

-

“La Chimera” (dir. Alice Rohrwacher)

Image Credit: NEON The third and most romantic installment in Rohrwacher’s informal trilogy exploring the relationship between Italy’s past and present, “La Chimera” finds the Tuscan filmmaker returning to the rustic charm and eternal regret of “The Wonders” and “Happy as Lazzaro” in order to stretch them across a richly textured canvas that spans from ancient Etruria to “The Crown.”

It begins with a man played by Josh O’Connor (never better) as he dreams of the woman he loved and lost. His name is Arthur, her name was Beniamina, and there is no hope of them reuniting on this mortal coil. But Arthur isn’t one to give up. Legend tells of a buried door that connects this world to the next, and this surly archaeologist is so hellbent on finding it that he’s become the leader of a ragtag gang of tombarolis — lovable grave-robbers, essentially — in the small village where his Beniamina once lived. He offers the group his sorcerer-like ability to dowse the location of ancient treasures, and in return they do the digging for him. What he ultimately turns up is a lush and lived-in adventure that beats Indiana Jones at his own game while posing the question that Rohrwacher has been circling for so long: Does the past belong to everyone, or does it belong to no one? —DE

-

“The Delinquents” (dir. Rodrigo Moreno)

Image Credit: MUBI Filmmaker Rodrigo Moreno’s pitch-black saga starts out as a familiar crime-gone-wrong story before it heads in a series of unexpected directions: It begins with a man who robs the bank where he works, with his intention of hiding the money until he’s released. In the process, he coerces a coworker into the scheme, and both men are forced to deal with the fallout as thrilling and comical twists unfold (including a most unexpected love triangle). By its third act, “The Delinquents” has the liberating air of a French New Wave movie, and folds in on itself to interrogate the very nature of its antiheroes’ quest until the journey becomes less relevant than the dream behind it. It takes guts to create such an entertaining genre experiment and then abandon it for something more profound and daring, but that’s exactly what makes “The Delinquents” such a bracing, unpredictable ride. —EK

-

“Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell” (dir. Thien An Pham)

Image Credit: Thien An Pham An intimate three-hour epic of deliberate pacing, Vietnamese writer-director Thien An Pham’s Camera d’Or-winning debut feature is a spellbinding tale of the soul’s unfathomable desire for the other-worldly; a film that itself borders on transcendental in its grace and gradual blurring of apparent truth and suggested fantasy.

“Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell” premiered in the Directors’ Fortnight section, where the filmmaker was previously recipient of the Illy Prize in 2019 for the short “Stay Awake, Be Ready,” in which a roadside accident at a street corner interrupted a conversation between three friends having a meal. That short seems loosely remade for the new feature’s opening scene, which expands the idea to explore a man’s attempted overcoming of a deeply unsatisfied life, taking him from urban Saigon to the hinterland of Vietnam, out of both familial necessity and a quest to make sense of where and how to proceed with his life going forward. “The embrace of faith is ambiguous,” offers the film’s grief-stricken hero, “I want to believe, but I can’t. I’ve tried searching for it many times, but my mind always holds me back.”

What follows is a metaphysical journey that steadily trains you in perceiving and eventually becoming lost in its sense of time, to the extent that you can almost forget the presence of the camera even when it is moving. Whether or not you’ve ever believed in a higher power, we’ve all questioned who we are, what we’re living for, and how to escape a certain mundanity in which modern society can box us. Based on the quality of his debut feature, Pham has certainly found his own divine calling with filmmaking. —JSW

-

“Fallen Leaves” (dir. Aki Kaurismäki)

Image Credit: MUBI Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki has been making bittersweet deadpan comedies for decades without changing his formula one bit. That makes the precision of his latest example all the more satisfying as it presents a master of his own homegrown filmmaking style in full command of the medium. “Fallen Leaves” is not unlike Kaurismäki staples such as “Match Factory Girl” and “Ariel” in that it follows a lonely woman (Alma Poysti) who drifts through aimless jobs when she meets a heavy drinker (Jussi Vatanen) who seeks companionship of his own. Meanwhile, the specter of a larger broken world hangs over the plot as an essential contrast to put small dramas in the context they deserve. Together this couple can’t fix the world, but there’s still a transcendent beauty to the way they learn to navigate it together no matter the hardships in store. The meet-cute dynamic has such delicate precision to it that you almost feel as though Kaurismaki is whispering it in your ear, and he’s more than welcome there: “Fallen Leaves” is cinema as a warm blanket in a cold world. —EK

-

“Killers of the Flower Moon” (dir Martin Scorsese)

Image Credit: Apple Studios Martin Scorsese may like to think of “Killers of the Flower Moon” as the Western that he always wanted to make, but this frequently spectacular American epic about the genocidal conspiracy that was visited upon the Osage Nation during the 1920s is more potent and self-possessed when it sticks a finger in one of the other genres that bubble up to the surface over the course of its three-and-a-half-hour runtime.

The first and most obvious of those is a gangster drama in the grand tradition of the director’s previous work; just when it seemed like “The Irishman” might’ve been Scorsese’s final word on his signature genre, they’ve pulled him back in for another movie full of brutal killings, bitter voiceovers, and biting conclusions about the corruptive spirit of American capitalism. But if the “Reign of Terror” sometimes proves to be an uncomfortably vast backdrop for Scorsese’s more intimate brand of crime saga, “Killers of the Flower Moon” excels as a compellingly multi-faceted character study about the men behind the massacre. Over time, it becomes the most interesting of the many different movies that comprise it: A twisted love story about the marriage between an Osage woman (the indomitable Lily Gladstone) and the white man who — unbeknownst to her — helped murder her entire family so that he could inherit the headrights for their oil fortune (Leonardo DiCaprio, giving the best performance of his career as the dumbest and most vile character he’s ever played).

Finding the right balance in this story is a challenge for a filmmaker as gifted and operatic as Scorsese, whose ability to tell any story rubs up against his ultimate admission that this might not be his story to tell. And so, for better or worse, Scorsese turns “Killers of the Flower Moon” into the kind of story that he can still tell better than anyone else: A story about greed, corruption, and the mottled soul of a country that was born from the belief that it belonged to anyone callous enough to take it. —DE

-

“May December” (dir. Todd Haynes)

Image Credit: Netflix A heartbreakingly sincere piece of high camp that teases real human drama from the stuff of tabloid sensationalism, Todd Haynes’ delicious “May December” continues the director’s tradition of making films that rely upon the self-awareness that seems to elude their characters — especially the ones played by Julianne Moore.

Here, the actress reteams with her “Safe” director to play Gracie Atherton-Yoo, a lispy former school teacher who became a household name back in 1992 when she left her ex-husband for one of her 13-year-old students. Now it’s 2015, the situation has normalized somewhat, and Gracie and Joe (a dad bod Charles Melton) have been together long enough that their youngest children are about to graduate high school. Their scandalous romance has settled into suburban reality… or so it would appear. Alas, the past isn’t quite ready to release its grip on these crazy kids just yet, especially once Gracie decides to roll out the welcome mat for a breathy TV actress who’s preparing to play her in an indie film about the scandal (Natalie Portman (phenomenally on pointe in a merciless performance). Inviting the stranger into her life seems innocent enough, but Gracie doesn’t quite understand what else she’s inviting into her life at the same time.

Written by Samy Burch, “May December” is a catty-as-fuck dark comedy that deepens Haynes’ longstanding obsession with performance while poking fun at the kind of actresses he clearly loves so much. The director’s tonal playfulness has sometimes been overshadowed by the unerring consistency of his emotional textures, but here, in the funniest and least “stylized” of his films, it’s easier than ever to appreciate his genius for using artifice as a vehicle for truth. —DE

-

“The Pot-au-Feu” (dir. Tran Anh Hung)

Image Credit: Gaumont There is something to be said for a simple dish made with the best ingredients by a trusted hand. Just as a perfect omelet made by a lover is more satisfying than an eight-hour feast laid on by a Prince, so it follows that a film like “The Pot-au-Feu” works, not in spite of, but because it focuses on executing its basic premise with enrapturing attention to detail. This is a story about love and food, which it presents as the same thing.

Sight unseen, it was always a mouth-watering prospect: two delicious French actors – Juliette Binoche as a cook and Benoît Magimel as her long-time lover and food-obsessed employer – feeding each other in Tran Anh Hung’s adaptation of a 2014 graphic novel reputed to be food porn. The promise of this set-up is delivered with gusto as the kitchen of a 19th century French manor house becomes the stage for the most elaborate foreplay you’ve ever seen. What “Call Me By Your Name” did for peaches “The Pot-au-Feu” does for syrup pears. Belonging to a fine tradition of intoxicating food films such as “Babette’s Feast”, “Julie & Julia”, and “Like Water For Chocolate,” “The Pot-au-Feau” pushes the notion of bonding through vittles a step further. Certain dishes are so inscribed by their creators that they act as memory itself, says the film, a sentiment that leaves a beautiful after-taste. —SMK

-

“Robot Dreams” (dir. Pablo Berger)

Image Credit: Robot Dreams Pablo Berger’s poignant animated feature, acquired by Neon out of Cannes, could very well enter the awards conversation this fall. The “Blancanieves” director’s first work with animation is a nearly wordless story of an anthropomorphized dog who acquires a robot buddy only to get it stuck on Coney Island, where the poor mechanical being gets stranded with low battery during the off-season. As the lonely canine attempts to rescue his companion and makes his way through an alienating pre-9/11 New York City, “Robot Dreams” strikes an astonishing happy medium between family-friendly entertainment and a powerful study of loneliness in the big city: It has a slapstick sense of play and storybook visuals, but its emotion cuts deep once said robot begins to dream. It’s been a while since a traditional 2D animated film managed such a tricky tonal balance (think vintage Pixar). “Robot Dreams” creeps up on you with a spell that lingers, and it’s a first-rate New York movie to boot. —EK

-

“The Settlers” (dir. Felipe Galvez)

Image Credit: MUBI It’s Chile during the turn of the last century. A wealthy landowner who’s bought up most of Tierra del Fuego recruits the Scotsman who manages his security to exterminate the Indigenous Selk’nam people on his land. The Scot only wants one man to accompany him, a mixed-race mestizo of Indigenous descent who’s barely out of his teenage years, but the landowner insists that MacLennan also take along a wily Texan with a strong drawl and a big rep.

So begins one of the most chilling art-Westerns to come along in some time, as provocative for its ideas, dialogue, and characterizations, as for the beauty of its empty landscapes. Felipe Galvez’s “The Settlers” may remind some viewers of a Budd Boetticher film when they’re watching it: following three men on horseback on a cross-country journey, it dramatizes questions of identity and belonging, and how these things can be written in violence. Most Boetticher-like, in a tight 98 minutes “The Settlers” says more than a lot of films double its length. It’s also a deeply felt work of activism with a message that needs to be heard in Chile. Just as nothing about the Pinochet coup in 1973 or the resulting dictatorship is taught in Chilean schools today, so is nothing about the genocide of the Selk’nam, a culture that is considered extinct, with only one living person today able to speak their language. This is a film that shows that, as easy as it is to forget about the past, it’s easier still when it was never taught in the first place. —CB

-

“The Zone of Interest” (dir. Jonathan Glazer)

Image Credit: A24 Holocaust cinema has so implicitly existed in the shadow of a single question that it would no longer seem worth asking if not for the fact that it’s never been answered: How do you depict an atrocity? Is seeing necessary for believing, or are some things too unfathomable to adequately capture on camera?

A Holocaust drama that’s defined by its rigorous compartmentalization and steadfast refusal to show any hint of explicit violence, Jonathan Glazer’s profoundly chilling “The Zone of Interest” stands out for how formally the film splits the difference between the two opposite modes of its solemn genre — a genre that may now be impossible to consider without it. No Holocaust movie has ever been more committed to illustrating the banality of evil, and that’s because no Holocaust movie has ever been more hell-bent upon ignoring evil altogether. There is a literal concrete wall that separates Glazer’s characters from the horrors next door (those characters being the commandant of Auschwitz and his family), and not once does his camera dare to peek over it for a better look.

The authorless quality of Glazer’s images frees the characters within them from the emptiness of moral judgment. The evil on display is never the least bit in doubt, but its failure to recognize itself as such is only so able to take shape in the absence of its limiting obviousness. By the end, “The Zone of Interest” insists that all of history’s most abominable moments have been permitted by people who didn’t have to see them, and while the film’s ultimate staying power has yet to be determined, its vision of normality is — as Hannah Arendt once described that phenomenon — “more terrifying than all the atrocities put together.” —DE