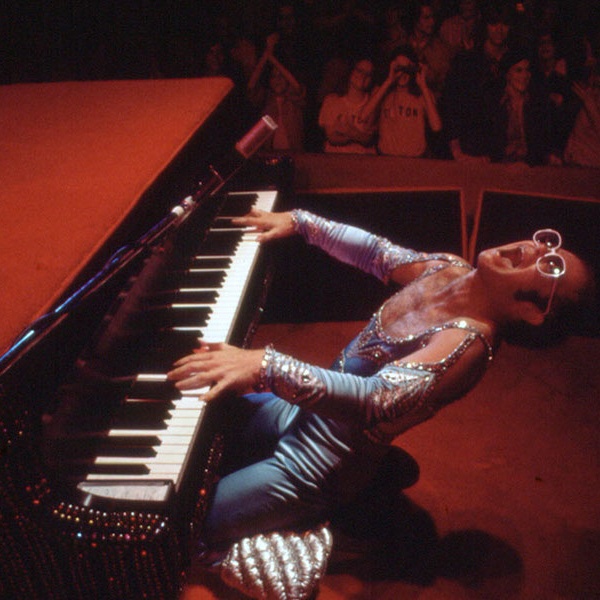

Russell Crowe is standing on a stage, playing an electric guitar. He’s singing “Folsom Prison Blues” by Johnny Cash, accompanied by a trumpetist, a drummer, someone at a keyboard, another guitarist, and even four backing singers. He starts rocking out to the instrumental section. The crowd, full of Czech film industry insiders, international critics, and fans, is undoubtedly entertained.

This is not yet another remake of “A Star Is Born,” but simply the kind of event you can expect to witness at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, taking place every summer in the Czech city and welcoming talent from all over the world.

First established in 1946, KVIFF went through a transformation in the early 1990s following the fall of communism. Karel Och, working at the festival since 2001 and its artistic director since 2011, thinks this shift explains how spectators themselves have changed.

“They didn’t really react at Q&A’s,” he told IndieWire. “They had the tendency to keep their sensations inside. But now, you can see a forest of hands immediately after the screening. They like to ask very sophisticated questions, which is a really interesting mirror of what’s going on in [our] society.”

Most screenings are indeed sold out, whether they be for films that played in Cannes, such as Karim Aïnouz’s “Firebrand,” which opened the Czech festival (with star Alicia Vikander present), or for smaller films having their world premieres, most intriguing amongst them this year being Luka Beradze’s “Smiling Georgia,” a 62 minute-long documentary about an infamous political campaign during which a candidate convinced poor Georgians to have their rotten teeth pulled out and promised them new ones, only to leave them toothless after his defeat.

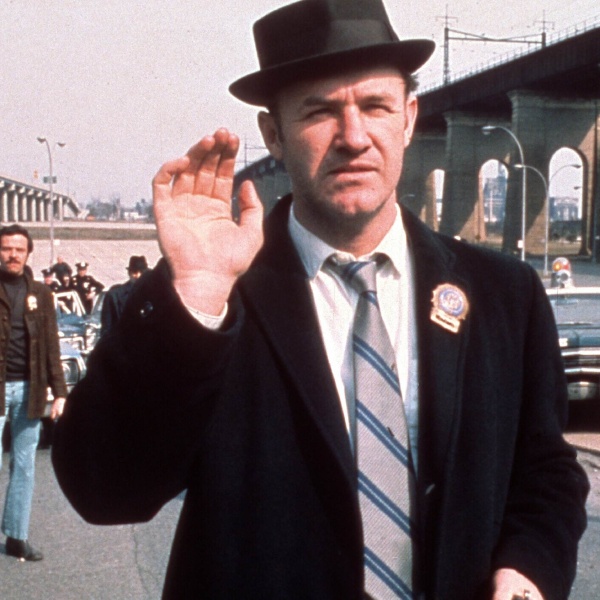

Stars like Crowe have always been part of the festival experience, with even Rita Hayworth attending the inaugural edition. A private company, the festival needs to please sponsors: “They’re like us in a way, you know? We like to spend time near the stars because if you love cinema, you’re inevitably in love with its glamour as well,” said Och.

The opening night gig was a way to attract Crowe in his music-man era, as are the career awards that the festival gives out every year — Robin Wright and Ewan McGregor were also welcomed at this 57th edition, each selecting a film from their respective careers to be screened.

This reliance on star power has, however, sometimes created controversy. Mel Gibson received the 2014 Crystal Globe for Outstanding Contribution to World Cinema, and while Johnny Depp has never received this award, he was invited to screen his films “Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan” and “Minamata” in 2021 while the scandal of his divorce from Amber Heard was in full swing and his reputation damaged by accusations of domestic violence.

In addition to receiving statuettes, recipients of the Crystal Globe are also asked to participate in the shooting of a trailer for the festival, typically directed by a Czech filmmaker working in black and white and poking fun at the very concept of awards. In a questionable move, the festival decided to shoot one such trailer with Depp as well, this time in color, in which the star shows off a Crystal Globe he stole and stuck his name onto.

KVIFF isn’t the only film festival unsure of what to do with filmmakers under scrutiny (TIFF, a much bigger festival, canceled the premiere of Ulrich Seidl’s “Sparta” at the last minute last year, and this year’s Cannes Film Festival opened with a film starring Depp and whose director has been sued for assaulting a journalist) but this indecisiveness is a real shame for a festival that has plenty to offer beyond glitter.

This year’s winner of the Crystal Globe Competition, featuring world or international premieres of fiction and documentary works, was the darkly funny and gut-wrenching “Blaga’s Lessons” by Bulgarian filmmaker Stephan Komandarev, which follows a 70-year-old woman trying to rebuild her savings after falling prey to a phone scam. Such bold Eastern European cinema is Karlovy Vary’s true specialty and the festival has become key for the Czech film industry, with filmmakers fitting their post-production schedules to the festival’s deadline.

The Proxima section presents debuts as well as audacious films from accomplished filmmakers. This year’s highlight for this writer was British production “In Camera,” directed by Naqqash Khalid, an almost experimental exploration of identity and survival in our modern world through the experience of a struggling actor. The main cast and crew of this small debut were invited to attend — as Och explained, filmmakers love the festival for “doing things partially the old way, honoring the fact that festivals are here to facilitate the encounter of the filmmaker with the audience.”

Even filmmakers whose works premiered in Venice or Cannes now want to support their work at KVIFF “because they don’t have that many opportunities anymore to meet those for whom they make films.”

The eclectic film selection stems from pure intuition. “What one of my professors at the faculty told us was to really sit down in the cinema and not think about anything, to just let the movie work you,” said Och, “and to just rely on the years of doing this job. Because the more movies you watch, the better you know your instincts, and ultimately, it’s the instincts that decide.”

This same genuine curiosity determines each year’s retrospective section, with the wild works of post-war Japanese filmmaker Yasuzô Masumura chosen this year by curator Joseph Fahim and screening to packed audiences. And if the team’s cinephilia remained in doubt, it’s worth noting that Och also allows himself to use his privileges as creative director to screen one film by John Cassavetes each year (“Minnie and Moskowitz” this time), simply for the pleasure of it.

Perhaps most strikingly, KVIFF benefits from its charming setting in a spa town where romantic upholstery and pink, yellow, or blue buildings along the river and up the mountain create a sense of being out of time and space. “It might be obvious, but people probably don’t realize enough how important it is to have a festival in a city where the majority of the guests do not work nor live,” said Och, who is based in Prague. “It’s such a challenge to prepare a lineup of films which are often demanding, because we’re talking arthouse cinema, [that will enter] the life of people who spend the day at the office.”

By contrast, Karlovy Vary offers a break from everyday life in an atmospheric environment, aesthetically verging on Wes Anderson’s idea of 20th century Europe but full of diverse and exciting cinema old and new — and with additional score by Russell Crowe.