For the first-time team-up between the Autobots and Maximals in the “Transformers: Rise of the Beasts” prequel, director Steven Caple Jr. (“Creed II”) was given a lot of creative freedom in designing and animating the characters. Gone was ILM from the previous six films, giving way to MPC and Wētā FX. MPC was the principal VFX studio and did all of the design work, but both had a hand in overhauling the Autobots and introducing the beast-like Maximals, which mix fur and flesh with their metal parts.

Production VFX supervisor Gary Brozenich (from MPC) oversaw the work. After studying the previous films, he met with Caple to discuss his vision for tailoring the animation and also consulted with previous director Michael Bay (who still serves as producer). Rather than continuing to push the hyper-realism of the Bay films, Caple wanted to make them look more straightforward, with a nod toward the G1 design of the original toys and animated TV series from the ’80s.

“That wasn’t the kind of movie that Steven wanted,” Brozenich told IndieWire. “But what I came away with from talking to Bay about it was the power of being able to find the equivalent of what you would do with a bounce card on set or reflector card next to an actor. We played with that throughout the film with these walking, talking, metallic, reflective characters, straddling the line between [photo-realism and hyper-realism].

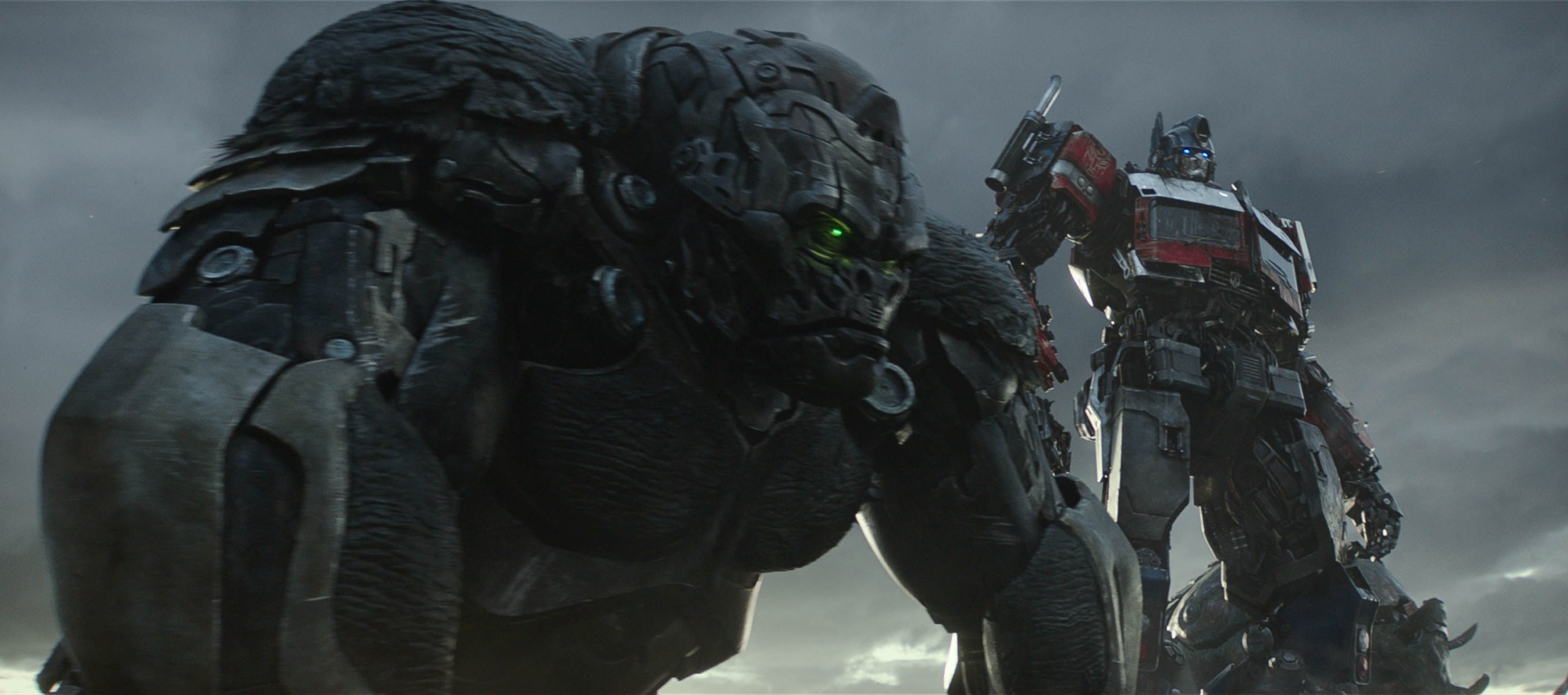

The first objective for Caple was to give the powerful Optimus Prime (voiced by Peter Cullen) a character arc as part of his origin story predating the 2007 film. This eases the world-weary warrior into joining the Maximals (led by gorilla Optimus Primal, voiced by Ron Perlman) in protecting Earth from the planet-eating Unicron (voiced by Colman Domingo) and henchman Scourge (voiced by Peter Dinklage).

“We wanted to give [Prime] a lot more human-like depth and for us to go on that journey with him to get to a very dark place where he’s down,” Brozenich said. “And he needs to find the beauty of humankind again, to be able to wanna save them.”

As a result, the director encouraged MPC to modify the design of Prime, returning to his original, boxier look. They also patterned his face after voice actor Cullen’s and added more emotion during dialogue scenes. Another important character was the newest sidekick, Mirage (voiced by Pete Davidson), the Autobot spy who projects holograms and transforms into a silver-blue Porsche 964 Carrera RS 3.8. “When Steven and I first met, the first character we talked about was Mirage, and this is way before Pete Davidson entered the frame,” added Brozenich. “But his take on him was streetwise like Tyler Durden from ‘Fight Club.’ He loved the fluidity of Brad Pitt’s character in that film and the sort of schizophrenic nature of him where he would turn on a dime.”

But with Davidson providing a lot of funny improv, this allowed the animators to tailor the animation around his vibe. The sporty look of the curvy Porsche also played a role in shaping the performance. “He was really sympathetic to camera, in a way that a lot of the other characters weren’t because they were so boxy in design,” said Brozenich.

One of the most significant developments was how MPC re-imagined the critical transformations from vehicles to robots with their own new proprietary tool. This allowed the animators to splice, separate, and re-arrange geometry on a model, in any given shot, and on any asset.

“For instance, if you took the car door at any point, I could tell them that this doesn’t look complex enough,” Brozenich continued. “Typically, there’s a tendency to have things go into more of a 90-degree perpendicular angle to each other. But when you start introducing non-linear angles and rotations, that’s when you start to feel the complexity of the object changing.”

Wētā, meanwhile, was recruited late in production to handle the opening introduction of the Maximal planet and the high-octane climactic battle inside a volcanic crater. They utilized their suite of proprietary tools to apply facial performance capture to rigid surface robotic models. In addition, they created their own tool for dealing with transformations, including one-offs for the Maximals as they prepared for battle. This was more involved with animals changing into robots. Since Wētā’s sequences were theirs alone, the handoff of MPC’s design work was pretty straightforward.

“Obviously everybody has their own proprietary rendering and shader technology, so we had to do that side of the thing and made their designs work within the language of our pipeline,” VFX supervisor Matt Aitken of Wētā told IndieWire.

Even though the beast-like Maximals are very much in Wētā’s wheelhouse (they leaned into their “Planet of the Apes” experience), the mechanical DNA of the Transformers was a new challenge for their rigging team. “That giant robot has to move in a way that supports their scale and the animation is really important,” Aitken continued. “We are used to applying detail to our creature work, making it authentic to help sell the realism. And detail is important with the Transformers in a different way, with the mechanical detailing and lots of moving parts, getting all that sense of detail working.”

There was also the opportunity to get more nuanced facial performance (with the aid of mo-capped doubles for reference) than on previous “Transformer” films. But it was on a very compressed schedule. “We wanted to provide our facial animators with an interface that they could immediately adapt to,” said Aitken. “So we made a decision at the start to leverage off the experiences that our facial animators have and combine them with a facial rig that they’re used to. So within each of our Transformers, we have a human face that’s been modified to match the shape of the robot.”

In terms of Wētā’s transformations, they had their own variation of the slice and dice method but pushed the task until the end when they could devote more attention to it. “As they’re crafting the transformation, they’re cutting it up into bite-sized chunks,” Aitken added. “But we needed to get the articulation that they require: splitting, edge beveling, and edge extrusions that happen dynamically during the transformation process.”