If you didn’t grow up in Pittsburgh (which boasted rival baseball greats the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords) or watch Episode 5 of the 1994 Ken Burns docu-series “Baseball,” you may not know much about the Negro Leagues. That’s about to change.

Sam Pollard‘s “The League” is an eye-opening slice of American baseball’s 154-year history. In fact, the recent rule changes imposed on the Majors by Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred were inspired in part by the practices of the Negro Leagues: while Babe Ruth focused on home runs (like many players today), these extraordinary Black athletes favored a fast, hit-and-run, base-stealing game.

“If you watch footage of Jackie Robinson from the ’40s and the ’50s, his style of play, his aggressiveness, all came from the Negro Leagues,” Oscar-nominated documentary director Pollard told IndieWire during a recent interview. “If you watch the players who integrated Major League Baseball, like Maury Wills of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Rickey Henderson, or Lou Brock, all those guys played a game that basically came out of the approach of the Negro Leagues. Now, the game got slower. So now Major League Baseball has reinterpreted and put back those rules to make the game as exciting as it used to be. Because Major League Baseball was an exciting game in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s.”

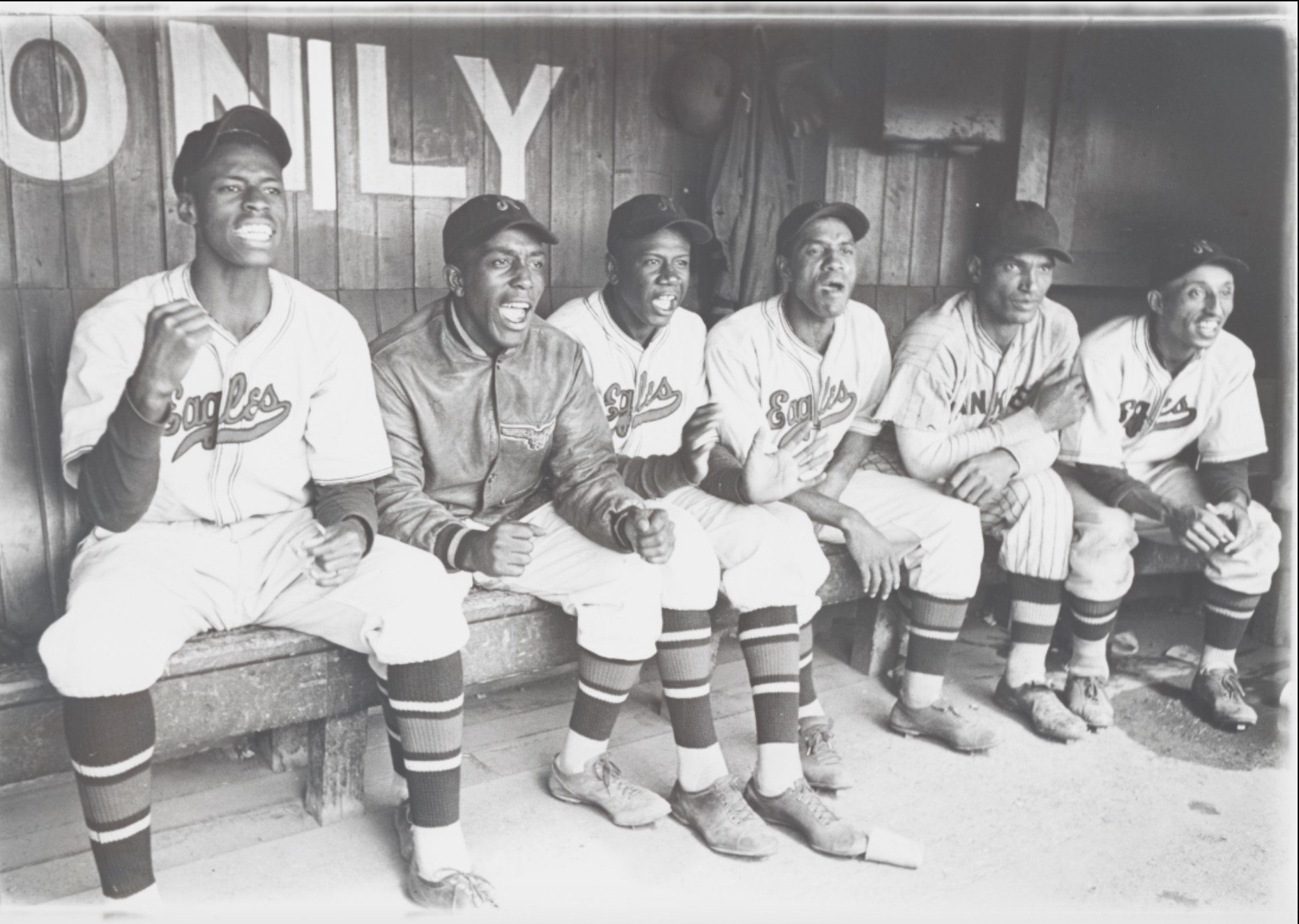

In the doc, Pollard dives into what video archives he could find to show us the legendary stars of the Negro League era, which officially lasted from 1920 to 1948. After Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson in 1945 (without compensating his team), he opened the floodgates for the Majors to poach the best Negro League players, from Satchel Paige to Willie Mays and Hank Aaron, putting the Leagues out of business.

Pollard said nobody knew that Branch Rickey “didn’t want to compensate the Negro League owners for signing Jackie Robinson or Roy Campanella,” he said. “We’ve always seen the story from the film ’42’ where Harrison Ford as Branch Rickey is a wonderful curmudgeon who loves Jackie and says, ‘You can’t show you have a temper, you got to hold it all in, it’s gonna be good for the game.’ Now we see there’s another side to Branch Rickey.”

The true Robinson history also shocked Oscar winner Amir “Questlove” Thompson (“Summer of Soul”), who joined “The League” as executive producer. “I grew up thinking that Robinson was this undeniable force of baseball athleticism, only to later find out that he was chosen for his patience, and his ability to take what was handed to him, which was not something that is easily digestible: hate, being jeered at, being ridiculed, having his life threatened, like you’re making history as as your life is being threatened,” Thompson told IndieWire. “He was specifically chosen because he can take it, which is an unfortunate burden to have to bear.”

On the other hand, Newark Eagles owner Effa Manley managed to drag some money out of the Chicago White Sox, Pollard said: “When Bill Veeck signed Larry Doby, she was able to get $10,000, which is for that time a huge amount of money.”

The film shows that as long as the Negro Leagues lasted, they often outperformed the white teams in drawing enthusiastic fans to brimming ballparks. They were among the most prosperous Black-owned business ventures in American history.

Having grown up in Pittsburgh, where he heard tales of the legendary baseball teams from his family, Thompson likes to shine a light on hidden history. “The lane that I’m occupying is unearthing parts of history that have either been forgotten about or unfortunately buried, neglected,” Thompson said. “We’re living in a time period right now in which people in certain parts of the country are literally trying to rewrite history. And oftentimes, looking in the rearview mirror is not a pastime for Black historians. I’m about restoring history and giving people a sense of where they came from.”

For Thompson, “Black history is American history. In the ’70s, Motown made the film with Billy Dee Williams and Richard Pryor, ‘The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings,’ a film about a Negro League team. We were basically just fed the narrative that one day, Jackie Robinson came along, and then it was Kumbaya. And that was it, like everything was equal and right. It wasn’t until this project that I realized a common thread of about five or six examples of African-American communities using their resources to build successful businesses. And literally, in the case of Tulsa, their lives being threatened for thriving and succeeding. And in this case, I’m now finding out that the Negro League was making much more money than national Major League Baseball was.”

One of the pivotal moments in bringing the white baseball owners around was a meeting with Broadway star Paul Robeson, who made the case that the Major Leagues should be integrated with the players who risked their lives fighting in World War II. “This story of integration is always a complicated one,” said Pollard. “There’s been a level of integration, but there’s still segregation in much of America. It’s a double-edged sword that we live with in this country. It’s never been an easy solution in terms of racial attitudes in America.”

Ten years ago, Pollard started out to make a documentary based on a book by Byron Motley about his father, Bob Motley, who had been a Negro League umpire in the ’40s and ’50s. It took a while to raise funds. Two-and-a-half years ago, Radical Media came in, followed by Magnolia and Thompson, and the scope of the film became much larger.

While Thompson was working with 40 hours of footage, an embarrassment of riches on “Summer of Soul,” Pollard had to make do with far less. “To find any substantial information is almost like a needle in a haystack,” said Thompson. “So I respect all the creative choices that Sam made to tell the story, when really not given the lion’s share of the history. It wasn’t like these games were televised, or that they were properly documented. These people were barely getting lodging and food, let alone someone to document them.”

Some of the rare treasures unearthed by Pollard’s archivists include footage of African-American players playing in the Caribbean and Mexico, which had been saved by Quincy Troupe, the son of a Negro League catcher. Producer Helen Russell found rare footage of perhaps the Negro League’s most famous players: Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and Cool Papa Bell.

“It was just wonderful to see some of the stuff that we had never seen before,” said Pollard. “And some of these Negro League lovers, they had placards, old tickets, baseball memorabilia cards.”

Next up: On October 6, PBS American Masters is showing Pollard’s doc about legendary drummer Max Roach, including performances by Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, Clifford Brown, and Abbey Lincoln.

And Thompson is working on his Sly and the Family Stone documentary (Disney/Onyx), inspired by rediscovering Stone’s music during the making of “Summer of Soul.” It was not lost on Thompson, he said, that “in the 10 days after the Harlem Cultural Festival, the one event that will be the paradigm shift turnaround of Sly’s life is going to occur, which is his performance at Woodstock. And Sly winds up doing a very, very slow self-sabotage to his career. This film is going to be about Sly Stone, but I’m going to tackle what we call ‘the burden of genius.’”

A Magnolia Pictures release, “The League” is in theaters with a VOD release to follow on Friday, July 14.