Editor’s note: This review was originally published at the 2022 Toronto Intertnational Film Festival. Neon releases the film in theaters on Friday, May 19.

A sharp and silly and deliriously romantic single-location saga about a hotel chain heir (Christopher Abbott) who’s blackmailed by his long-time dominatrix (Margaret Qualley), Zachary Wigon’s “Sanctuary” unfolds like a kinky cross between “Punch-Drunk Love” and an off-Broadway play. The results are delightful and exasperating in almost perfectly equal measure until a last-minute hail Mary ends the movie on such a high that even its hoarier stretches seem like they were worth the walk in hindsight.

It starts with color swirls and a heart-stirring Ariel Marx score that sounds like it could be the overture of a musical; it ends with a rush of blood to the head. In between, it’s sustained by its performances. Not just the go-for-broke performances from two of the most inherently watchable young actors of their time, but also those of their characters, both of whom are so trapped by their parts in life that their kinky role-playing sessions together have become a lifeline that neither one of them may be able to live without. At a certain point, who they pretend to be with each other might be more honest than who they are on their own.

“Sanctuary” is a story about identity and control, but it’s a movie about the combustible energy generated by putting two beautiful people in a confined space and watching them vye for sexual dominance. More twisty than twisted, Micah Bloomberg’s script begins on an unassuming note, as a “lawyer” named Rebecca (Qualley) arrives at the lavish suite atop Denver’s Porterfield Hotel where her “client” Hal Porterfield (Abbott) is waiting to go over the paperwork that needs to be completed before he can assume control over his late father’s empire.

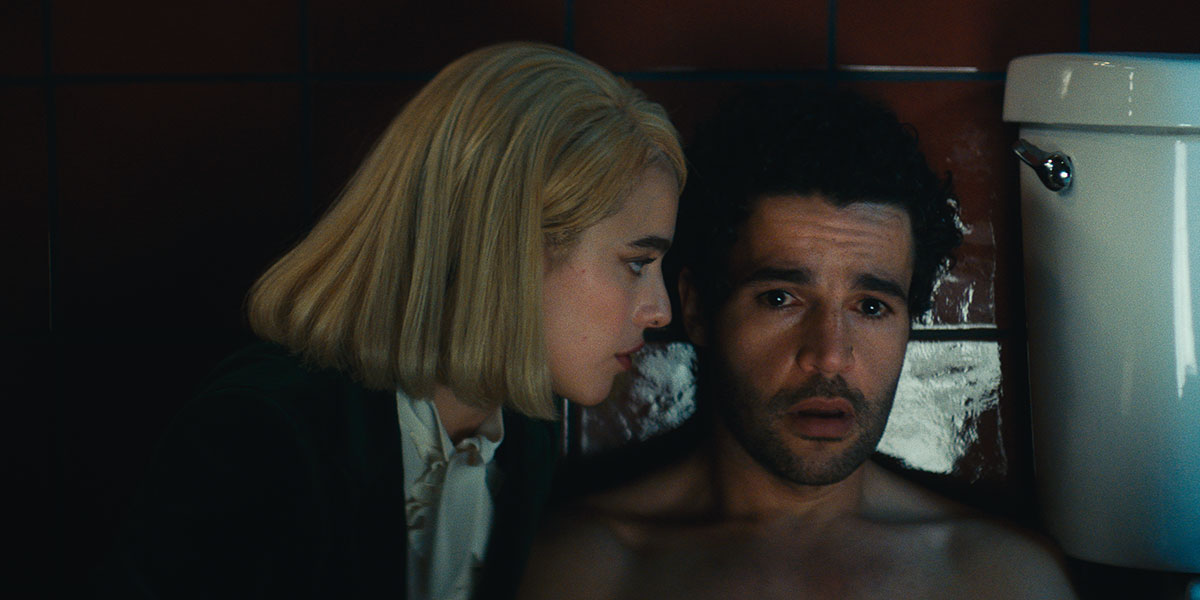

But several things seem off about the situation. For starters, Hal claims to be 6’3” and weigh 200 lbs., clear exaggerations that clash against the self-loathing humility of his shrinking demeanor. Rebecca, meanwhile, seems too young to be handling a case of such importance, and while gorgeous lawyers do exist in the wild, they don’t tend to show up at someone’s hotel room sporting a blonde wig, a runway-worthy emerald green pantsuit, and a degrading questionnaire that interrogates their client’s sexual history. It isn’t long before the masks slip off and a half-naked Hal is scrubbing the dirt off of daddy’s marble bathroom floors while his mistress reads him for the filth that he is.

But something seems off about this too, if only just. Rebecca keeps veering off the script that Hal wrote for them to follow, as if she were trying to assert the same control over her client in real life as he surrenders to her in their roleplay. Where a less probing version of this film might be preoccupied with hiding the “truth” of Hal and Rebecca’s arrangement, “Sanctuary” dispenses with the parlor games and rug-pulls early on so that it can shift its focus to the slippery dynamic behind it. If the question of authenticity vs. performance is predictably central to the last two acts of Bloomberg’s script, it’s not framed in the context of whether Hal and Rebecca are lying to each other so much as in the context of why they’re lying to themselves.

Acting is everything in “Sanctuary,” and (almost) everything is acting. Even more so than most two-handers, this is a movie that’s carried by its cast, and Abbott and Qualley are extremely up to the task. Both are inspired choices. Abbott because the role of a whimpering Roman Roy plays against his natural sense of aggression — creating a rich dissonance between Hal’s pitiful helplessness and the character’s knotted sense of control — and Qualley because of all the same reasons that she’s always great, chiefly the way she mixes child-like flittiness and vulnerability with a deranged aura of danger to the point that Hal isn’t sure if he should trust Rebecca with his life or call the cops on her. Or both, somehow.

It’s a part that requires several extreme (and I mean extreme) swings of emotion, most of which only work because Qualley makes Rebecca feel both invincible and powerless at the same time. Things between she and Hal do become physical at certain points — sometimes alarmingly so — but the crux of Qualley’s performance can be found in the close-up reaction shots where you see her character processing the situation in real-time. We don’t know if she’s plotting to destroy Hal or to shame him into becoming the man he was always meant to be (whatever that means!), but “Sanctuary” derives so much of its rather innocent charm from the pleasure of trying to figure that out.

At least Wigon, whose only previous feature was 2014’s similarly scaled (and similarly sharp) “The Heart Machine,” always seems to have a clear understanding of what makes Rebecca tick. He and cinematographer Ludovica Isidori initially shoot the character like she just stepped out of a giallo movie — all sharp angles and velvet edges, as if she were designed by the same people who furnished the lushly upholstered suite in which 99 percent of this movie takes place (a refreshing change of pace from most of the ultra-contained pandemic fare that’s been made thus far).

The stiff camera reflects the scripted precision of Hal and Rebecca’s little charade for the first third of the film, before coming so unhinged in the middle section that it seems to be dancing along with the cast. There’s no disguising that almost every scene in “Sanctuary” takes place within the confines of a hotel suite, but Wigon frames the space dynamically enough for the movie to own the first lesson of the book that Hal’s father wrote about business: “You have to match up your insides with your outsides.”

It’s a lesson that Hal himself has struggled with for so long that he’s started to miss the forest for the trees, leaving Rebecca the only force in his life capable of restoring any measure of perspective. As she diagnoses it, he “wants to be reprimanded for what he thinks are inherent flaws and then rewarded for coming into compliance,” but the solution to that problem eludes them both.

That leads to a lot of vamping during the film’s eventful but somewhat emptily chaotic second act, during which Rebecca goes into goblin mode and tries to burn everything down so that “Sanctuary” has something to build up again as it careens towards a succinct but satisfying finale that elevates the film and its characters alike. Some may find those last few beats a bit too neat, but I couldn’t help but smile at how forcefully they put the story’s true “perversions” to bed. Their methods may be unconventional, but these aren’t irrational (or even unusual) people.

As Rebecca puts it to Hal: “I just want what I deserve relative to what you have.” Who among us has ever asked for anything else? What makes “Sanctuary” such a salaciously enjoyable slice of snack-sized fun is how it argues that some people have more to give than they would ever know without the right person to take it from them.

Grade: B

“Sanctuary” premiered at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival.