Writers on strike worry about what artificial intelligence might do to their livelihood, but actors already know. Their work is based on voice and appearance, which AI clearly can replicate and manipulate — but the law around regulating AI is complicated.

SAG-AFTRA is pushing for informed consent and compensation in the union’s ongoing negotiations (which conclude this week, after a brief extension) with the studios. The language the WGA has proposed in its own fight — and what the DGA has now enshrined — is framed around protection of job loss from AI, but that’s not enough for actors. The DGA currently has it in writing that AI is not a person and that producers must consult with a director before using AI. That’s still important to actors and a good start, but SAG-AFTRA will aim for broader protections specific to its members.

IndieWire talked to experts in AI filmmaking, visual effects, and publicity law to map out the three biggest concerns that should be on SAG-AFTRA’s mind.

Who Can Be the AI Me?

Tom Hanks was one of the first actors to work with AI, via the mo-cap production of Robert Zemeckis’ 2004 “The Polar Express.” The tech and the film were then viewed as cutting edge, if only partially successful; it was a box-office flop and some critics complained that its characters seemed not-quite human and mired in the “uncanny valley.” Zemeckis and Hanks are now in production on “Here,” a 2024 Sony title that will use AI to de-age Hanks to play multiple iterations of his character.

The actor was a producer on “The Polar Express” and is producing “Here,” but he realizes that AI also could extend his performances long after he’s dead — and there’s little he can do to control the outcome.

In a May 13 interview on “The Adam Buxton Podcast,” Hanks described it as a “bona-fide possibility right now” to “pitch a series of seven movies that would star me in them, in which I would be 32 years old from now until kingdom come. I could be hit by a bus tomorrow and that’s it, but my performances can go on and on and on. Outside of the understanding that it’s been done by AI or deep fake, there’ll be nothing to tell you that it’s not me.”

Entertainment attorney Simon Pulman, a partner at Pryor Cashman, told IndieWire that, when it comes to filming a commercial, there are existing publicity laws that protect an actor’s likeness. For instance, can’t create an AI Brad Pitt or Sandra Bullock and have them endorsing a product without paying them.“ But if AI is used to create a composite, a completely digital creation that has been trained on the physical appearance, voice, or mannerisms of an actor, but doesn’t necessarily look and sound like the actor, that’s where things get “tricky,” he explains. And protections get a lot more complicated if you perform an AI resurrection.”

“That is certainly an area that varies state by state, there are certain organizations that purport to own the likeness of dead celebrities, and they will pursue this pretty aggressively,” Pulman said. “You’ve got two types of questions: What happens when people increasingly use AI to put famous dead people in commercials, and what happens when you put dead people in motion pictures?”

Publicity protections, Pulman explains, are for commercials. A movie or a TV show is a work of expression, and Pulman says SAG-AFTRA is looking for “express, bright line guidelines to replicate actors’ names, likeness, and performance” in a way that’s an extension of their existing contract and to supplement existing law. That’s important, because actors like James Earl Jones, 92, have already consented to his voice being used to create synthetic versions of Darth Vader for years to come.

The guild has already said it expects the use of AI and digital doubles to be bargained through the guild, and members under commercial and low-budget contracts already have some protections around likeness, but any guidelines will need to be specific to this contract with the AMPTP. Guidelines released last week by IATSE may provide a hint to how other guilds are thinking, but Pulman says it’s hard to get a full picture, simply because the technology is moving so fast.

“There are certain use cases that are easier to prescribe for. On one end, the very benign, and on the other, abuses that SAG will want to limit,” Pulman said. “In the middle is more of a gray area, because we can’t see all of the uses.”

Do I Have Creative Control Over My AI Self?

AI can give actors the ability to seem as if a single performance can contain multitudes, since it allows editors to manipulate an actor’s mouth and face to choose different words or languages. In the Lionsgate rated-R movie “Fall,” TrueSync AI manipulated the actor’s mouth to match dialogue alterations for a PG-13 version.

Actors may be on board with that as long as it does not change their performance, but there’s no guarantee it won’t. What if the director or studio doesn’t like an actor’s creative choice? Or if a screenplay change means a director needs a shot of the actor smiling rather than frowning? AI gives the director the power to quickly make the change, or try multiple alternatives, rather than expensive reshoots that demand the actor’s presence.

The key lies in the actor’s “source code.” That’s what Remington Scott, CEO of VFX company Hyperreal, calls the AI model based on an actors’ prior performances. Hyperreal’s mission lies in empowering “creators to own, copyright, and monetize” their digital identities, such as the de-aged Paul McCartney or the Notorious B.I.G. that performed in the metaverse. These were created with specific data sets around an individual’s movement, speech, their appearance, and the logic behind their actions. The more data that the model ingests, the more lifelike and specific it becomes.

“If I have all of Paul Newman’s motion, everything he does — walking, talking, standing, sitting — and we put that into our database, now we can have a director say, ‘OK, Paul, get up, walk to the door, turn, say your line, and walk out.’ And then he does it,” Scott said. “It’s Paul Newman doing it.”

Pulman predicts SAG-AFTRA will likely say that AI can’t be allowed to modify the fundamental character of a performance, to which the AMPTP will counter with the exception of dubbing, subtitling, color corrections, and other common fixes in post-production.

But the guild will also want to know how those AI models are being trained and who makes those decisions. Edward Saatchi, the Emmy-winning producer of Oculus Story Studio who now runs his own AI shop Fable Studios, uses Jack Nicholson as an example. Is the model trained on the Jack in “Chinatown,” “As Good As It Gets,” or both? How does that affect the AI performance or image?

“Which one are you getting?,” Saatchi asked. “Is that just up to the director? Can the director change his mind halfway through?” In 2021, Saatchi produced a VR film that premiered at the 2021 SXSW Film Festival, “Wolves in the Walls,” adapted from Neil Gaiman’s comic of the same name. It starred Lucy, an AI-enabled character developed with an early version of ChatGPT.

Saatchi is now producing “White Mirror,” an animated AI feature film, made by artists with access to AI technology from Runway, Open AI, Midjourney, and NVIDIA. Usually, an animated feature costs at least $10,000 per second, but with “White Mirror” the costs are, according to Saatchi, coming in lower than $10,000 per minute — 60 times less.

“If [a director is] like, ‘OK, now you’re going to be funnier. Now, I want you to be this,’ It can get pretty complicated pretty fast,” Saatchi said. “You’re giving the director an incredible — maybe wrong amount — of control.”

Who Owns My AI Self?

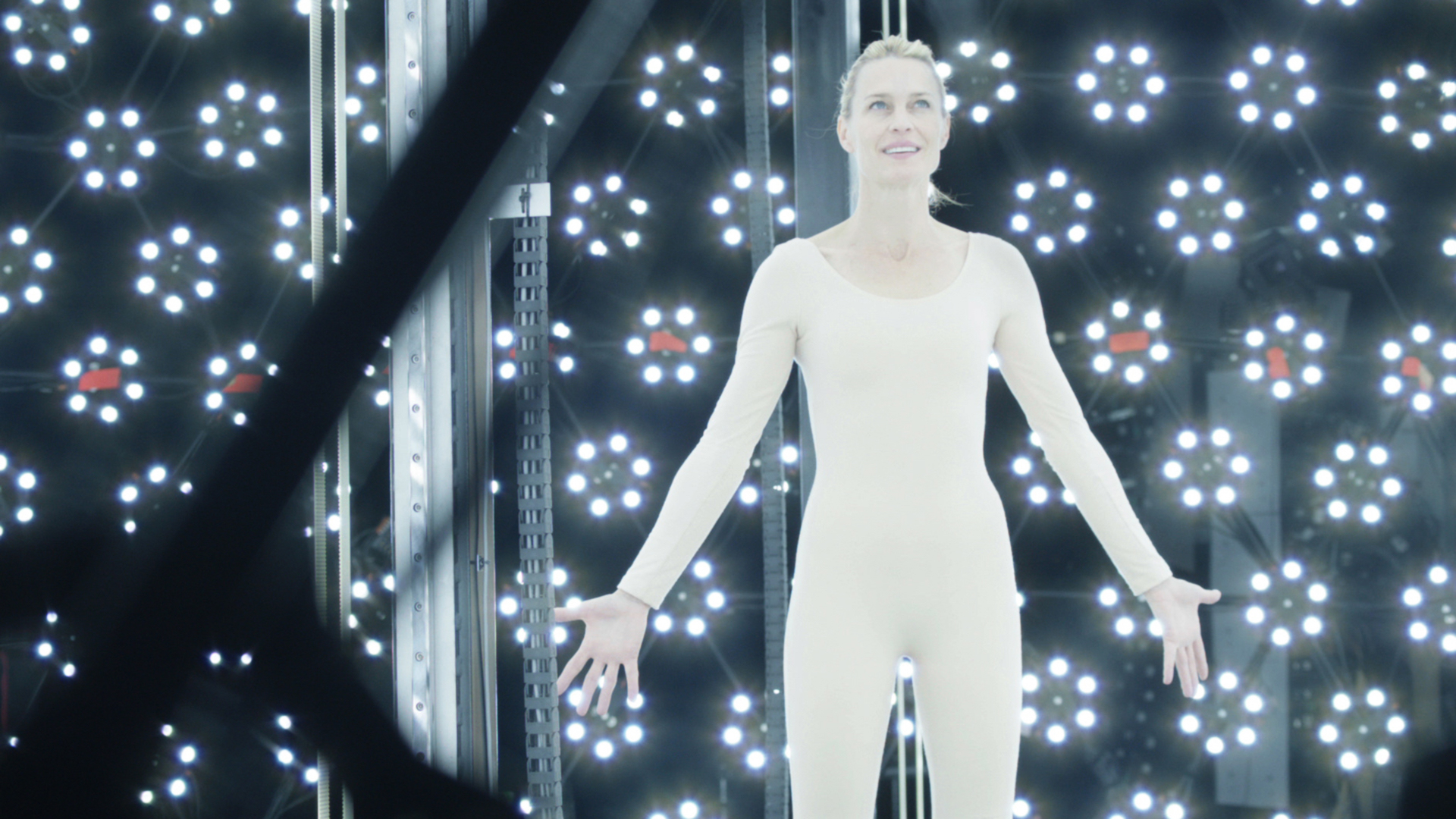

Deepfakes and voice modulators can be used to replace makeup, costumes, or the awkward VFX dots on an actor’s bodysuit. “In real time, the actor is able to see themselves — as is the director, as are the co-stars — accurately as this younger person and act in the moment,” Saatchi said. “With this, you’ll be able to be someone else.”

What’s much less clear is who gets paid for that performance. “In the next 12 months, every single actor’s estate or actor’s production company or actor’s team will establish the guardrails of how they want to have that used so that they can be compensated fairly for it,” Saatchi said.

A 2013 sci-fi film starring Robin Wright, “The Congress,” made the case that one company could own an AI likeness for all eternity that creates performances for decades to come. Saatchi said he suspects AI development will settle around the system we have now in which a bespoke AI model is used on a film-by-film basis, and Pulman agrees that the guild will ask for any AI model to be destroyed after its use.

Here’s the tricky bit, according to Scott: An actor should control the rights to their own image, but the IP that’s valuable are the images of an actor in a movie or show. Those images are owned and copyrighted by studios, which need to be paid when generative AI uses the material to create new content. The industry hasn’t figured that one out yet, either.

Currently, generative-AI tools scrape whatever they can find on the internet and use it to train their models — and no one is being paid. If training data went into a generative-AI model owned and authenticated by the actors themselves, there would be something in it (financially) for SAG members.

Scott says he has the right way to do it. When building an actor’s digital double, Hyperreal develops “source code” derived from an individual’s motion, voice, appearance, and logic. The company can create detailed, 3-D models around iconic images and moments that might otherwise be copyrighted. Scott’s clients then own the underlying data of the digital model and can license it for future use.

“We’re working on building the AI so it isn’t cross-contaminated by ChatGPT,” he said. “What we’re building is very specific to the talent. So that way they own it. It’s not off-brand. It is the true source code of that person.”