Queer movies and TV shows are all well and good, but arguably even more important is the existence of great LGBTQ documentaries. Fiction can help provide great representation and tell moving queer stories, but documentary does something else entirely: it preserves entire communities’ stories as snapshots in humanity’s kaleidoscopic history.

Documentary filmmaking has (almost) always been a relative safe haven for LGBTQ cinema, particularly smaller, experimental docs created by independent filmmakers. For years, mainstream films largely sanitized and ignored the LGBTQ community — but the documentary format allowed queer people to capture the truths of their lives that went otherwise undepicted. Great LGBTQ documentaries stretch back as far as 1967, with “Portrait of Jason”: a fascinating profile of a gay nightclub performer. Other early greats provided the first mainstream depictions of vibrant gay subcultures, like 1991 ballroom doc “Paris Is Burning” or 1967’s drag film “The Queen.” And still others provided sweeping and inspiring depictions of the LGBTQ rights movement, as with “Before Stonewall” or “The Times of Harvey Milk.” Some documentaries released today provide the most thorough depictions of the AIDS crisis ever rendered, reconsidering the federal government’s horrific silence in the light of the 21st century, as with “How to Survive Plague.”

Today, there are no shortage of queer documentaries worth championing, like the Oscar-nominated animated masterpiece “Flee,” or music doc “Sirens.” This year has already seen the premiere of another great one: D. Smith’s “Kokomo City.” A profile of three Black trans sex workers and their lives, the film bowed at Sundance to critical acclaim, and will be receiving a limited release this July. In celebration of “Kokomo City,” let’s take a look back at some of the historical greats in LGBTQ documentary cinema. This list considers projects that either profile LGBTQ community members, or focus on queer history. Entries are listed in order of their U.S. premiere date.

Here are the 15 best LGBTQ documentaries of all time.

With editorial contributions by Tambay Obenson and Eric Kohn. [Editor’s note: This article was published on June 28, 2023, and has been updated since.]

-

“Portrait of Jason” (Shirley Clarke, 1967)

Image Credit: ©Milestone/Courtesy Everett Collection An experimental work of cinéma vérité, “Portrait of Jason” focuses exclusively on the life of a gay nightclub performer and hustler Jason Holliday. And we do mean exclusively: Holliday is the only person on screen in Shirley Clarke’s documentary, which sees Clarke recount his troubled life story. But he’s not the only person in the room; Clarke, her husband, and the rest of the crew frequently chime in off camera to question Holliday’s narrative and hurl insults his way. This approach — where a white director openly mocks her Black documentary subject — has caused some controversy and critical reevaluations over the years, but Holliday’s singular onscreen presence can’t be denied. —WC

-

“The Queen” (Frank Simon, 1968)

Image Credit: ©Kino International / Everett Collection One of the earliest documentary works to explore the thriving world of drag culture, Frank Simon’s “The Queen” focuses on a group of New York queens competing in the 1967 “Miss All-America Camp Beauty Contest.” Narrated by its master of ceremonies, Flawless Sabrina, the film captures all of the fun and drama surrounding the event, and became a touchstone of drag culture. In particular, a speech from competitor Crystal LaBeija became often-quoted, getting sampled in a Frank Ocean song and lipsynced by Aja in Season 3 of “RuPaul’s Drag Race: All Stars.” —WC

-

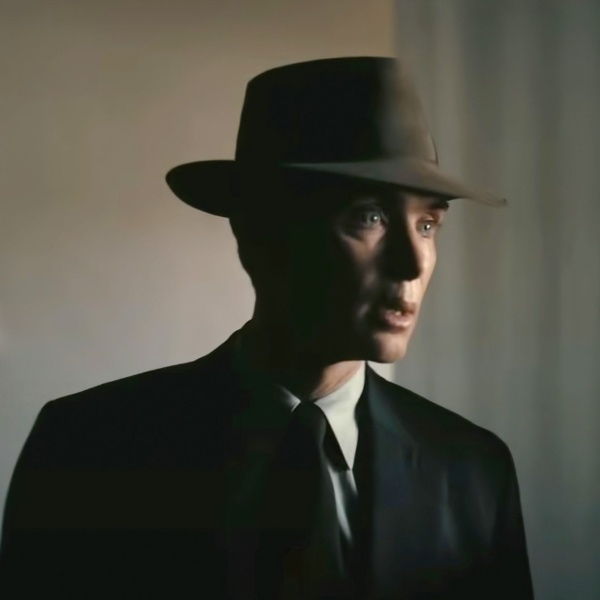

“The Times of Harvey Milk” (Rob Epstein, 1984)

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection Produced after the death of its title subject, Rob Epstein’s “The Times of Harvey Milk” uses archival footage, interviews, and narration from Harvey Fierstein to tell the story of the assassinated political figure. Through the words of Milk’s allies and supporters — including Anne Kronenberg, Tom Ammiano, and Bill Kraus — the swift hour-and-a-half doc tracks Milk’s rise from activist to a symbol of gay political acheivement, and the trial of his murderer Dan White. In 2012, the film was selected for preservation by Library of Congress for the National Film Registry. —WC

-

“Before Stonewall” (Greta Schiller and Robert Rosenberg, 1984)

Image Credit: ©First Run Features/Courtesy Everett Col / Everett Collection “Before Stonewall” is only a scant 87 minutes, but it has an impressive scope, focusing on the forgotten and obscured history of America’s LGBTQ community prior to the 1969 Stonewall riots. The film features revealing and detailed interviews with many LGBT artists and activists from before the advent of the modern gay rights movement, including Allen Ginsberg, Craig Rodwell, José Sarria, Barbara Gittings, and Evelyn Hooker. Due to its invaluable portrait of early LGBTQ advocacy, the film was selected for National Film Registry preservation by the Library of Congress in 2019. —WC

-

“Tongues Untied” (Marlon T. Riggs, 1989)

Image Credit: Signifyin’ Works and Frameline Distribution Civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer said, “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. put it this way: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” In sum, any commitment to liberation must be executed in all of its intersectional complexity. Marlon Riggs’ landmark essay film gives voice to Black gay men, documenting their perspectives on the world as they confront racism, homophobia, and marginalization. It broke new artistic ground by mixing poetry, music, performance and Riggs’ autobiographical revelations. The film was embraced by Black gay audiences for its unapologetic authenticity, as well its serving as a fierce response to oppression. It opened up opportunities for dialogue among and across communities, while being lauded by critics for its vision. But it faced considerable controversy, with many deeming it “poronographic” and protesting a 1989 PBS broadcast and the National Endowment for the Arts’ funding of the title. Nevertheless, the film’s lasting impact is undeniable. —Tambay Obenson

-

“Paris Is Burning” (Jennie Livingston, 1990)

Image Credit: ©Off White Productions/Courtesy Everett Collection The most definitive film account of ballroom culture during the ’80s, Jennie Livingston’s “Paris Is Burning” is essential — and has risen above controversy. Several participants sought legal action due to feeling cheated out of financial compensation for their work on the project, and Livingston faced accusations of parashooting and exploitation. That said, “Paris Is Burning’s” document of New York’s ballroom community remains a vital and fascinating watch years later, featuring incredible footage of the competitions and dancing and enlightening interviews with several prominent ball icons: Pepper LaBeija, Dorian Corey, Angie Xtravaganza, and Willi Ninja, to name just a few. Many of these icons have since passed away, which makes revisiting “Paris Is Burning” — and its intelligent look at the racism, poverty, and homophobia that the queer community dealt with during the AIDS crisis — an even more vital watch. —WC

-

“Nitrate Kisses” (Barbara Hammer, 1992)

Image Credit: Barbara Hammer Barbara Hammer, an establishing voice in lesbian film and a formative figure in culture’s broader understanding of feminism in the late 20th century, makes her documentary directorial debut with “Nitrate Kisses.” The unscripted work from 1992 is an experimentally structured essay, juxtaposing intimate footage of (then) contemporary queer sex with vestiges of LGBTQ culture, including intercut footage from 1933’s taboo homoerotic film “Lot in Sodom.” —AF

-

“Shinjuku Boys” (Kim Longinotto and Jano Williams, 1995)

Image Credit: Screenshot/Youtube One of the rare documentaries to focus on LGBTQ life in Asia, “Shinjuku Boys” is set in the titular Tokyo district, the epicenter of the city’s gay subculture. Kim Longinotto and Jano Williams’ cinéma vérité film focuses on three hosts — Gaish, Kazuki, and Tatsu — who work for the New Marilyn Club, a nightspot mostly frequented by heterosexual women. All three of the film’s leads are trans masc, and the film focuses on both their home and work lives, as they share their own insights and complicated thoughts on sex and their gender identity. —WC

-

“The Celluloid Closet” (Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, 1995)

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection Based on Vito Russo’s seminal 1981 book of the same name, Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman adapt Russo’s text and analysis of queer themes in classic film through a combination of interviews with film professionals and scholars, as well as footage of the late Russo’s lectures to promote the book. Featuring analysis of over a 100 films, narration from Lily Tomlin, and interviews with industry professionals like Whoopi Goldberg and Shirley MacLaine, the doc’s examination of hidden queer themes in classic movies has since become a staple of queer theory classes in film school. —WC

-

“Southern Comfort” (Kate Davis, 2001)

Image Credit: Screenshot In her 2001 portrait of the late Robert Eads, titled “Southern Comfort,” documentarian Kate Davis brings a remarkably sensitive lens to intimate footage captured during the last year of the transgender man’s life. Eads was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 1996, but was denied treatment by countless doctors who saw taking on a trans patient as a liability — until it was too late. Enmeshed with Eads’ chosen family in Georgia, Davis fully explores the complex familial relationships, straight and queer, as they existed when Eads passed in 1999. The movie was later adapted into an off-Broadway stage musical, which faced some controversy when predominently cisgender actors were cast in the roles. But the film itself remains a respectul and richly moving consideration of loss. —AF

-

“Tarnation” (Jonathan Caouette, 2003)

Image Credit: Mubi There aren’t enough autobiographical documentaries made by queer filmmakers. Jonathan Caouette’s Sundance darling from the early aughts is argument enough for why we should have more of them. Carefully examining his family relationships, most notably with his troubled mother Renee, Caouette charts more the 20 years of his life through home movies and family photos. The film faced considerable controversy at the time of its release, with many arguing that Caouette’s treatment of Renee was exploitive and unethical. But today, Caouette’s film remains a gem, capturing the exquisite undying love of a gay son and generations of oppression suffered by women, straight and queer. —AF

-

“How to Survive a Plague” (David France, 2012)

Image Credit: ©IFC Films/Courtesy Everett Collection Journalist David France’s “How to Survive a Plague” reflects on the harrowing fight of LGBTQ activists during the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and hits even harder in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. The global health crisis from 2020 aroused new anger in those who remember the horror wrought by the U.S. government throughout the 1980’s and early 1990’s, when its homophobic silence on the HIV/AIDS crisis left hundreds dead or dying. This 2012 documentary can’t account for all that new context, of course. But France’s work is so comprehensive that even a decade later it does a dazzling job examining how marginalized people can make change — and inspiring its audience to fight back against a negligent system. —AF

-

“I Am Not Your Negro” (Raoul Peck, 2016)

Image Credit: ©Magnolia Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection “I Am Not Your Negro” operates on many levels at once: It’s not only a fresh vessel for James Baldwin’s own analysis of Black life in America but a platform for his assessment of other great thinkers who informed his views. Raoul Peck, an undervalued Haitian filmmaker who has shifted between narrative and documentary projects for nearly 30 years, uses a remarkable foundation for this sweeping exploratory piece: a 30-page manuscript Baldwin wrote in 1979, as part of an uncompleted book project that delved into the lives of Medgr Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. All three activists died before they turned 40; Baldwin worked alongside, then outlived, all of them.

The movie injects Baldwin’s voice through a voiceover performance by Samuel L. Jackson that’s one of his very best performances in ages, while Peck shifts between archival footage of his four subjects (including Baldwin) and contemporary moments to throw the timeless resonance of Baldwin’s words. It’s at once a perceptive history lesson and a resurrection. —EK

-

“Flee” (Jonas Poher Rasmussen, 2021)

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection Animated documentaries are a small but potent subgenre, and few films make as good use of the medium as “Flee.” Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s film tells the life story of his friend Amin Nawabi (an alias created for the movie), an Afghan man who fled his home country as a refugee when he was a child following the outbreak of conflict in the region. The experiences that eventually brought Amin to Denmark are painful and still weigh on him as an adult, and the film sees him share his story with Rasmussen and his partner for the first time. Aside from archival footage, the entire film is animated reconstructions of both Amin’s past and his present life.

The animation serves a few purposes for the film: It helps keep Amin anonymous even as he shares his story with the world, but the dreamy, slippery art style and the occasional forays into abstraction are perfect for the story, portraying the fear, nostalgia, and longing within Amin’s account of the past. Once you watch “Flee,” you might wonder if all documentaries should be animated. —WC

-

“Kokomo City” (D. Smith, 2023)

Image Credit: Magnolia Pictures/D. Smith The directorial debut of D. Smith, “Kokomo City” focuses on the lives of four Black trans sex workers who live in Georgia and New York, shining a light on the joy and hardships they face. The documentary premiered at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival to critical acclaim, and won the Panorama Audience Award at Berlin Film Festival. Sadly, its critical success was mired in tragedy, as one of its subjects — Koko Da Doll — was murdered the April after its premiere. In a statement responding to the tragedy, Smith said: “I created ‘Kokomo City’ because I wanted to show the fun, humanized, natural side of Black trans women. I wanted to create images that didn’t show the trauma or the statistics of murder of Transgender lives … It’s extremely difficult to process Koko’s passing, but as a team we are more encouraged now than ever to inspire the world with her story. To show how beautiful and full of life she was.” —WC