During the opening frames of Sam Pollard’s “The League,” a wistful and profound documentary about the rise and fall of the Negro Leagues, baseball hall-of-famers Hank Aaron and Monte Irvin share how they played the game as kids, even when they had nothing more than broomsticks.

As footage of Black kids playing on a sandlot rush by, what’s being discussed isn’t merely successful men reminiscing about their past hardships, they’re talking about how they overcame those obstacles through resourcefulness and guile. Pollard’s newest incisive documentary about one of the largest Black-owned businesses in America, the Negro Leagues, is filled with those gems of perseverance and adaptation.

And yet, Pollard doesn’t skirt from the deeply felt dangers that afflicted these athletes living under the cloud of systemic racism. He tells this history through his narration and chronologically. He begins by straightening a misconception: Though Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, he was not the first Black man to play in the major leagues.

In 1884, for instance, Moses “Fleetwood” Walker became the first Black man playing for a professional team when he suited up for the Toledo Blue Stockings. Black people routinely played with and against white folk until 1883, when Cap Anson of the Chicago White Stockings (now referred to as the Chicago Cubs) threatened to never take the field if an African American was there. Thus, beginning the color barrier.

Pollard smartly connects the color barrier with the later 1886 Supreme Court ruling Plessy v. Ferguson, which instituted the separate but equal doctrine. He further charts how a broader need to improvise felt by the entire Black community, took hold in the rise of Black newspapers like the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier, and in the formation of the Negro Leagues and its World Series by the legendary Black pitcher/manager/owner Rube Foster in Chicago.

The introduction of names like Moses “Fleetwood” Walker and Robe Foster demonstrates the comprehensiveness Pollard is aiming toward: He wants to show the full history of Black American baseball. He does so through diagraming the strata of the first Negro Leagues and its sharp fall following Foster’s early death. He then dives into the second formation of the league, making teams like the Birmingham Black Barons, Kansas City Crawfords, and the Homestead Grays household names for Black America.

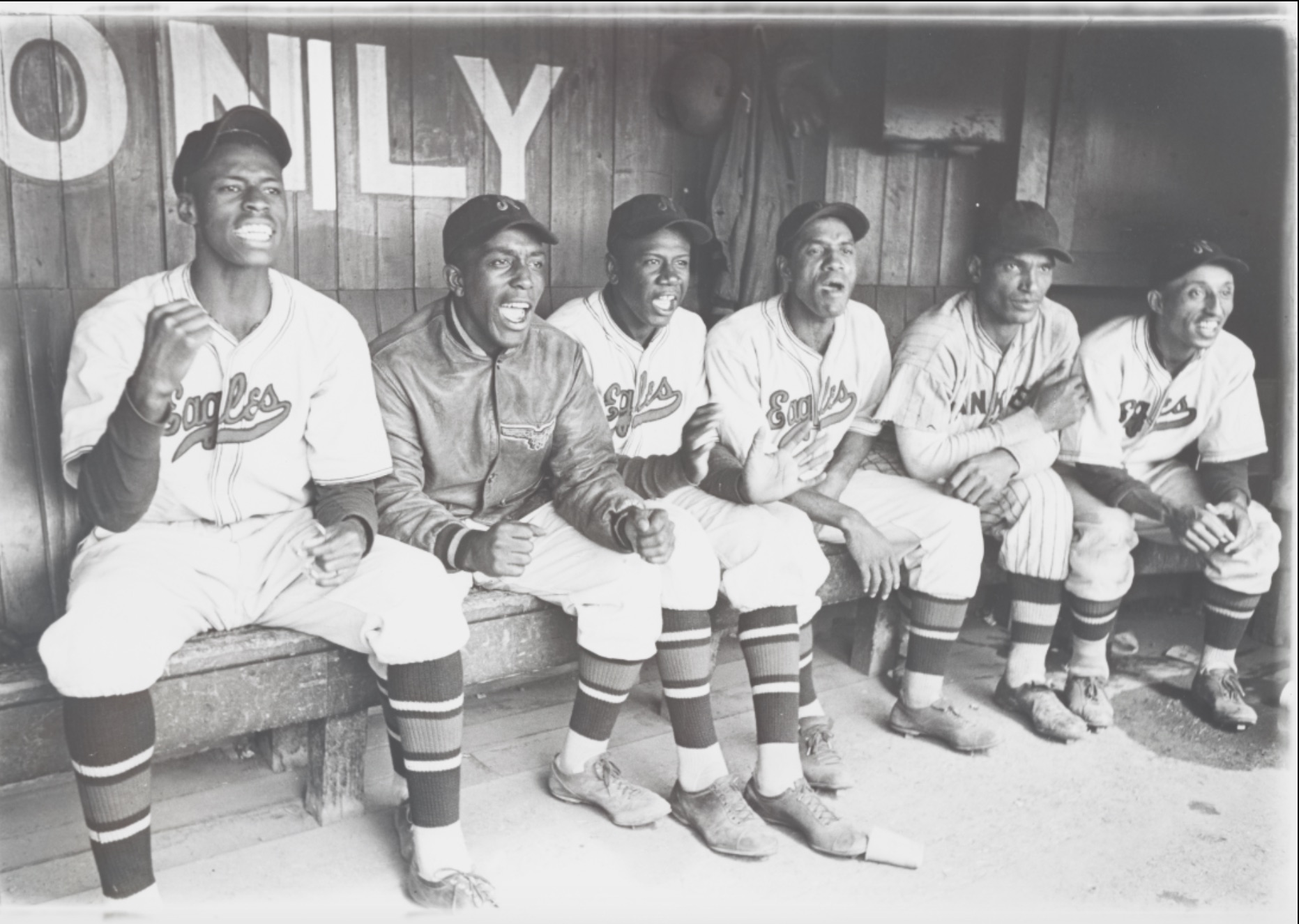

The documentary also covers Effa Manley — the co-owner of the Newark Eagles — and through the exchange of Black and Latinx players between North and Central America and the Caribbean. Through these stories, Pollard offers a rarely discussed three-dimensional conception of Black baseball.

The care in telling what’s been an erased history — though, to be sure, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum has done much to cradle what remains — is evident in Pollard’s many wise choices. He uses statistics to give viewers contemporary comparisons to legends like Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige. He employs the words of Bob Motley, a former Negro League catcher and umpire, to offer a vivid, colorful first-hand accounting of the harsh life faced on a segregated road by these athletes. It’s made all the more intimate by Pollard’s decision to personally narrate Motley’s writing; his voice gives the film a cool, easy-going sense of memory.

Pollard shoulders such care, not just because it’s simply his job as a documentary filmmaker, but because there are so few films that exist about the Negro Leagues. “Soul of the Game” and “The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings” are exceptions. The mere presence of this film is a continuation of Pollard’s ability to fill the unrecorded void.

The Civil Rights history of America, particularly the small and large figures who have affected it, have long interested Pollard. While “The League” isn’t composed in the same structure as say, “Mr. Soul!” or “MLK/FBI,” it does follow in the thematic footsteps of “Lowndes County and the Road to Black Power,” a documentary he co-directed with Geeta Gandbhir. “Lowndes County” covers the fight by a Georgia county to fight Jim Crow by integrating into local political offices, under the auspices that having Black people in positions of power — sheriffs, mayors, congressmen — would eradicate systemic racism. While the film is a powerful testament to their work, it boldly ends with one of the participants questioning the wisdom of integrating into a burning building.

“The League” attempts to make a similar movie. Gorgeous stills of Black people in their best Sunday fineries making their way to the ballpark and Black players visiting Black-owned restaurants, and interviews with the likes of Maya Angelou, inform us of the community support these teams received. Footage of packed ballparks, fans enraptured by the skills and precision by these players, punctuated by Dave Marcus’ distinct editing and the jaunty score, brings the scenes of revelries and superhuman feats back to life. By the time we arrive at the integration of baseball by Robinson, we come to appreciate what was gained, but we’re also privy to what was lost.

Now, the Nergro Leagues do not exist. Black ownership — whether real estate or businesses — remains a persistent battle. While MLB celebrates Negro League Baseball’s greats, whether through induction in the Hall of Fame or by virtue of Jackie Robinson Day — when every player wears Robinson’s 42 — per USA Today, the percentage of African Americans in the majors is at its lowest since 1955. The after effects of integration on the modern baseball landscape is the one component missing from the film. Then again, a full examination should probably best be saved for another documentary.

Still, as a living record of the history of the Negro Leagues — it’s role in shaping America, in the prospects of upward mobility, in providing a playing field for Black folks to express themselves — Pollard’s “The League” is a rich, engrossing, and necessary tribute to a critical early wave in the Civil Rights movement.

Grade: A-

Magnolia Pictures releases “The League” in theaters today with a VOD release to follow on Friday, July 14.