The strike remains a hot-button conversation, but the topic has changed. The writers are a given and the directors made a deal; today, it’s all about the actors.

The Screen Actors Guild (SAG-AFTRA) begins contract negotiations June 7; its contract expires June 30. If SAG-AFTRA joined the writers on strike, it would mean a near-total shutdown of the industry.

SAG took the rare step of calling for a strike authorization vote and goes into the talks with of 97.91 percent of its members willing to go on strike if a fair deal isn’t reached.

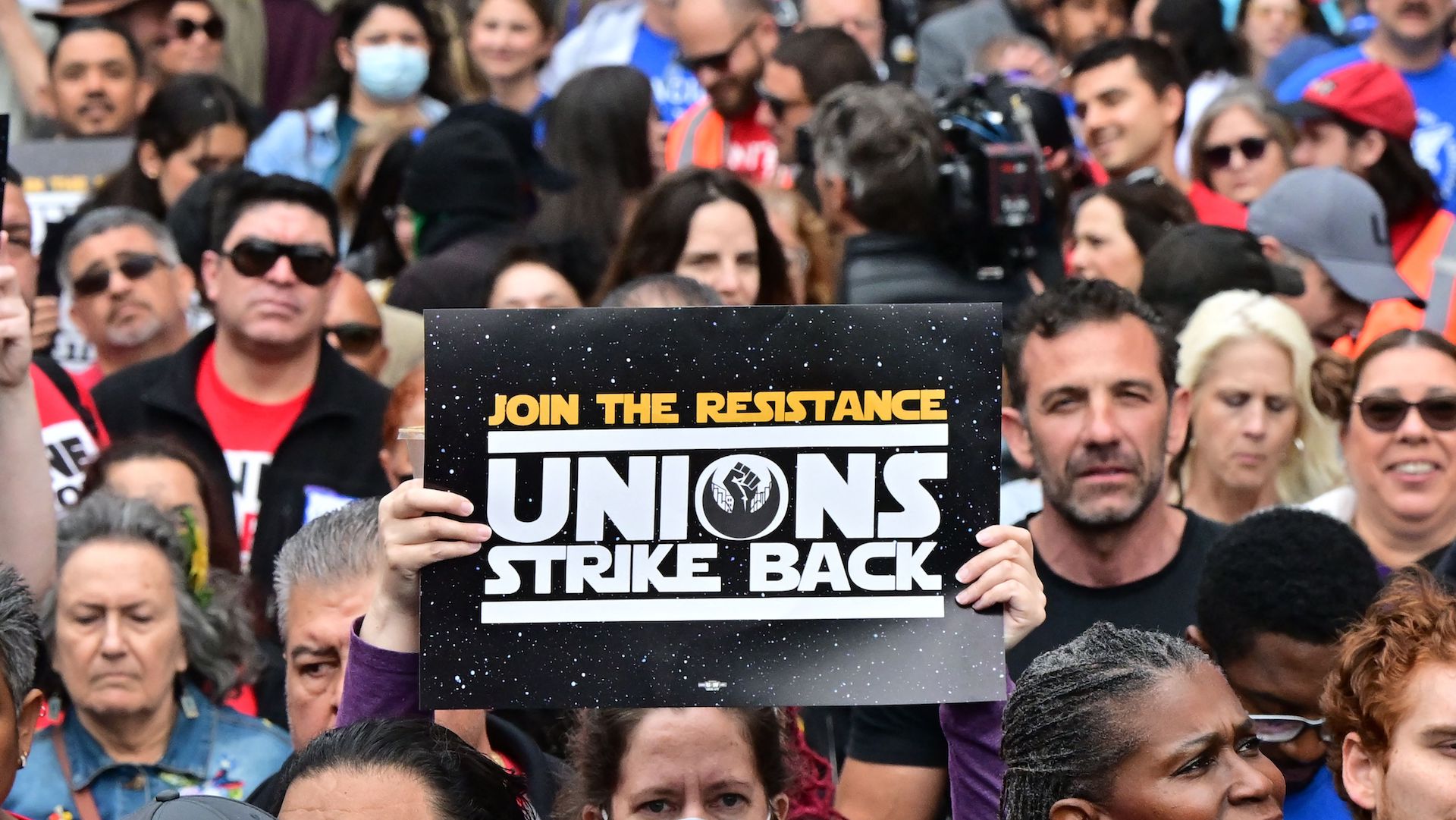

“We’re really at an inflection point in the industry,” SAG-AFTRA chief negotiator Duncan Crabtree-Ireland told IndieWire. “There are some issues that are really time sensitive and of crucial importance perhaps in ways that aren’t always the case. It’s an important moment for the labor movement in the entertainment industry and in the broader economy in this country. Our members are energized and feeling empowered in ways they haven’t in the past. That’s in part due to the extraordinary solidarity that we’ve seen with other industry unions, writers and directors of course, but also Teamsters, the basic crafts and others.”

Like the writers strike before it, we figured you might have some questions.

When was the last time SAG went on strike?

The last (and only) time that actors went on strike against the major studios was three months and three days in 1980, lasting from July until mid-October. The work stoppage against the TV networks and studios included NBC, CBS, and ABC, and film studios Paramount, 20th Century Fox, and Universal. Actors also boycotted the Emmys; only one of the 52 acting nominees, Powers Boothe, appeared. Film and TV production was shut down, with the exception of some game shows, soap operas, educational programs like Carl Sagan’s “Cosmos: A Personal Voyage.” Hollywood lost millions each week.

One of the key 1980 issues was residuals tied to VHS releases. (Only two percent of households even had a VCR.) Actors wanted 12 percent of gross revenue on home releases; studios gave 4.5 percent, but with overall pay raises of 32.5 percent.

Beyond that, the guild struck against global advertising firm Bartle Bogle Hegarty back in 2018; that lasted 10 months. The longest strike in the guild’s history was 11 months between 2016-2017 in a fight with 11 major video game publishers.

When SAG and AFTRA (American Federation of Television and Radio Artists) were separate unions back in 2000, the two joined forces and went on strike for a new commercial contract. Advertising firms wanted to roll back residual payments for commercials on network TV to match how actors’ flat-fee payments for cable ads. Actors got a significant pay bump and some wins in the still-nascent Internet advertising space, but failed to get cable residuals. That six-month labor action is considered one of the larger, more costly strikes in American history.

The negotiations that begin this week would affect SAG’s entire membership of over 160,000 individuals and the guild would fight with the studios on issues they believe speak to economic inequality and workers’ rights.

Why do things feel different this time?

SAG members have joined writers on the picket lines to demonstrate their solidarity. While the DGA deal may suggest the studios’ thinking, negotiators are unlikely to feel bound by their terms. The actors’ guild has also made clear, as did the WGA, that the DGA’s tentative deal will not impact their own negotiating agenda.

The lack of clarity about the SAG negotiations means indie film productions are struggling to obtain insurance necessary to start productions, as IndieWire recently reported. Others have preemptively pushed back their start dates until the fall and are planning for the worst while hoping for the best.

How aligned are the guilds?

Despite some faux-pas commentary by SAG president Fran Drescher, the DGA, SAG, and WGA have much in common on a few key issues: higher minimums, streaming residuals, AI, and data transparency.

Like writers and directors, actors believe that residuals should provide a “meaningful share of the economic value” of their performances. All guilds believe the formula for calculating streaming residuals, especially for how these shows are viewed globally, needs to improve.

Like the writers (and directors), actors want data transparency so they can benefit from streaming successes. Also like writers, actors are in a position where fewer episodes of TV and longer breaks between seasons mean relying on residuals to sustain them during extended gaps in jobs.

The DGA in its tentative deal made progress on that front; in theory, the WGA and SAG can build upon it. However, even the DGA’s deal does not match inflation rates — especially for the many SAG-AFTRA members who work at scale.

What about AI?

The DGA won important language stating that AI cannot be considered a “person” or replace the work done by members. For actors, companies are already using sophisticated digital models of actors, replicating their likenesses and voices for projects. Other guilds don’t address how AI deepfakes can be a potential abuse of performers.

SAG will focus on ensuring actors must give informed consent about using their likeness and that they’re paid appropriately for doing so. It also will ask questions about training AI data sets on actors’ performances; no one wants to be replaced with a completely synthesized performance. SAG-AFTRA already has contract language for AI when it comes to commercial performers or for low-budget productions.

As Crabtree-Ireland wrote in a guest blog for Variety on AI, SAG-AFTRA’s position is companies must go through the union to negotiate terms to use an actor’s likeness in any way.

“What’s important to understand is that SAG-AFTRA is not fighting to ban the use of AI,” he wrote. “Whether on screen, in music or video games, or any of the other areas we cover, the technology opens up new creative possibilities, but it cannot come at the expense of people.”

The new battle: Self-Tapes

The actors have a unique concern in self-taped auditions, aka self-tapes. The guild says self-taped auditions, which became commonplace during the pandemic, are “unregulated and out of control” and put a costly burden on actors in the audition process.

No one wants to get rid of self-taping altogether, which have been great for accessibility. They broaden opportunities for underrepresented groups and people around the world who might not otherwise get a shot to audition in-person. So the guild isn’t looking to put the genie back in the bottle and ban them.

For actors, self-taping means they don’t receive real-time feedback — but beyond that, the demands can go out of control. They’re asked to film themselves from multiple angles, or while driving, or climbing on furniture. In some cases, auditions verge on becoming full-blown productions that may demand camera purchases, lighting, and an editor.

At least in one instance, a casting office was royally called out for offering to help actors with their self-tapes by charging them a fee to film in its studio space. Other businesses have sprung up around this trend and SAG wants to reel it in.

Now What?

Not everyone is thrilled that the DGA cut its own deal while the writers are striking, but getting the AMPTP on the record on AI, residuals, and establishing higher minimum pay lets other guilds focus more on other issues.

If negotiations don’t go well for SAG, virtually all production will shut down. TV seasons and release dates for movies will push back. If no one knows when production might start, the market will come to a crawl. The Emmys will almost certainly be in jeopardy, and streamers and networks will start feeling the pinch on a lack of content.

No one wants that, but there’s also a sense that it might be worth it. “There’s a sense that workers are stepping up now and saying, ‘Hey, we’re not going to let these big corporations run roughshod over us,” Crabtree-Ireland told IndieWire. “We’re going to stand up for ourselves and people in this country are going to support us doing that because it’s how everyone feels. There’s an economic inequality issue in this country in general that people are recognizing, there is a problem with excessive corporate power that people are recognizing. And I think we find ourselves at a moment where we can really do something about that, and we intend to.”