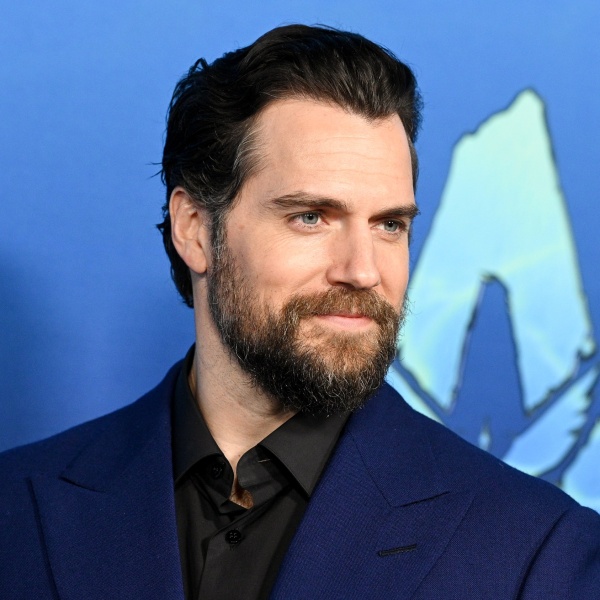

Vincent (Karim Leklou) is the kind of man who is so unremarkable that middle age seems destined to render him invisible. He posts sad selfies that make you wonder if he’s ever seen a photograph before. He cracks weird little “jokes” about how the intern at work is late with his coffee, despite being reminded that the intern doesn’t do coffee runs. His girlfriend recently dumped him. The man radiates such a pathetic energy that you just want to give him a hug — or perhaps a book of Civil War trivia to occupy his lonely nights.

So why, then, does everyone who sees him try to kill him? It’s a very good question that “Vincent Must Die” never has to answer.

From the moment we meet Vincent, quite a few people appear to agree that he must die. Everyone from new interns to longtime colleagues and total strangers on the street become possessed with an overwhelming desire to beat him to death from the moment they make eye contact. Stéphan Castang’s film cleverly opts to steal a leaf from the “Groundhog Day” playbook and never reveals the cause of the phenomenon. Instead, the film becomes a character study that examines what might happen when a man who is basically the human embodiment of the color beige is treated with the kind of animosity that’s usually reserved for John Wick.

Vincent is a trooper, and he appears content to keep going into work at his architectural firm every day and simply putting up with the occasional beating. But his boss sits him down and explains that the daily attacks have turned into a distraction at the office. He asks Vincent to work from home — which seems like a good compromise, until the kids in Vincent’s apartment building start attacking him in the halls. When he gets caught beating up the elementary schoolers in self-defense, his neighbors understandably question his alibi about kids attacking a 40-year-old man for no reason. The incident turns him into a pariah who can’t be seen leaving his apartment while the neighbors are awake.

At a certain point, Vincent realizes that “living in human society” is not a proposition that has a lot to offer a man with his newfound condition. So he decides to go on the lam, where other men begin to notice that he never makes eye contact with anyone. These men have a tendency to find each other, and Vincent learns that he’s not alone in his ailment. They’ve formed an underground society called The Sentinel, where they share survival tips on a discreet online forum.

If you want to survive as a Sentinel, there are a few rules you have to learn very quickly. You need to learn to stitch up your own wounds, because hospital workers will probably try to kill you. You need to delete your social media accounts, because people will see you in photographs and try to find you. And you need to get a dog, because they’re the only species that won’t betray you and they can identify the scent of someone who has decided to kill you.

Vincent retreats to his father’s decaying vacation home in the country, where he can be left alone to peruse his survivalist forums in peace. But grocery shopping is now impossible, so he begins parking outside a local diner and asking them to carry large amounts of food to his car. Despite radiating awkwardness and misanthropy, he somehow vibes with Margaux (Vimala Pons), the waitress tasked with delivering him his weekly food supply.

They spark up a new connection that’s only hindered by the fact that she occasionally tries to kill him. But while his fellow Sentinels have sworn off human contact entirely, Vincent and Margaux become convinced that it’s worth trying to find a workaround. She agrees to regularly spend time with him wearing handcuffs and blindfolds so that they can get to know each other without any unplanned attacks. The lengths they have to go to just to enjoy the occasional date become more and more extreme — but when Vincent sees the deaths of despair that are beginning to overtake his lonely friends, they become more determined to make it work.

“Vincent Must Die” gets started with an absolute bang. The darkly comedic first act is filled with genuine laughs as everyone in Vincent’s life tries to calculate the minimum amount of empathy that they’re supposed to offer this man that they don’t particularly care about. His therapist suggests that the attacks are the result of his attention-seeking behavior — a laughable suggestion considering his timidity — and one of Vincent’s attackers considers filing an H.R. complaint against him because of the inconvenience that the incident caused.

Unfortunately, the very plot elements that make the beginning so much fun end up weighing down the rest of the film. The genius of the premise is that Vincent is so bland and vanilla that you can’t possibly understand why people hate him so much. But Leklou might be too good at playing a sad sack with nothing interesting about him. Once he drops out of society and removes himself from conflict, you’re left watching a character study about a character who isn’t worth studying.

It becomes clear that the appeal didn’t lie in Vincent himself, but in the way he interacted with the world. His inability to navigate the nuances of office politics was wildly entertaining. Watching him order sad takeout meals and attempt to fix his septic tank by himself, not so much. His romance with Margaux never shakes the aura of being a contrived plot device, because it’s just never believable that anyone with a pulse would see this guy as a love interest.

Castang and screenwriter Mathieu Naert seem to tease us with the multitude of exciting paths that the film could go down before ultimately choosing the least interesting one. Instead of continuing with the dark comedy or fleshing out the mythology of The Sentinel, they take the darkest route and leave us with something that begins to resemble a generic zombie movie by the end. The natural response to the first few dozen attempts on Vincent’s life is righteous indignation at the poor man’s mistreatment. But after an hour and a half, it’s fair to wonder if the possessed mob is onto something.

Grade: B-

“Vincent Must Die” premiered during Critics’ Week at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival. It is currently seeking U.S. distribution.