Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” stars Cillian Murphy as the famed scientist whose Manhattan Project gave us the nuclear bomb. The movie both follows Oppenheimer‘s successful 1945 Trinity Test and its fallout, when the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki left him stricken with guilt and determined to do something about it. Nolan’s filmmaking gets inside his subject’s head and his fears of nuclear annhiliation. The filmmaker has said that he wishes more people were aware of that dangertoday — but does his movie occupy that same perspective? IndieWire’s David Ehrlich and Eric Kohn traded some thoughts on the matter, with a little extra perspective on Barbenheimer for good measure.

Warning: There are a few spoilers in this conversation.

ERIC KOHN: J. Robert Oppenheimer built the most powerful weapon in human history and, after it decimated thousands of lives in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, spent the rest of his life condemning its use. This ironic trajectory sits at the core of Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer,” not only in terms of its biographical angle but within the confines of the filmmaking itself.

The movie operates as an extension of Oppenheimer’s existential dread, and his impulse to warn the world that the threat of nuclear annihilation is very much a real thing. But that warning has lived at the forefront of modern times ever since…well, the decimation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Almost eight decades later, how much does “Oppenheimer” actually add to the alarm bells ringing ever since then?

Like most of Nolan’s wheel-spinning adventures through the magic of the editing process, the movie jumps and back forth through time as if enmeshed in Oppenheimer’s memories. The result initially puts the cart before the horse: We’re aware of his guilt and dread, as well as the persecution he faced from the U.S. government for speaking his mind, even before we see him oversee the Trinity Test at Los Alamos.

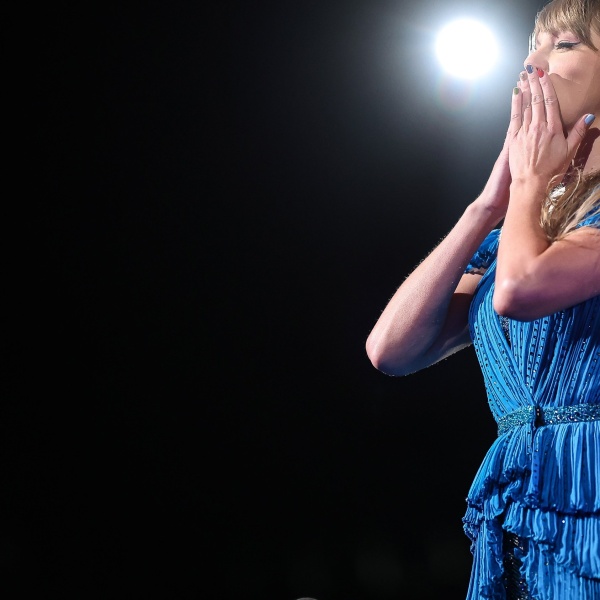

Despite the fireworks of that sequence, much of the movie unfolds as a dense, talky drama among physicists, war hawks, and a few of the women coping with the toxicity of powerful, obsessive men. (Emily Blunt as Oppenheimer’s frustrated wife, and Florence Pugh as his ill-fated lover, hover in a miniature Sirk-like melodrama alongside the rest of the proceedings.) Because “Oppenheimer” has more in common with Paul Schrader’s moody, guilt-strick “man in a room” dramas than any kind of blockbuster spectacle, it succeeds as rather intimate portrait of what such an extreme moral conundrum can do to a person’s soul.

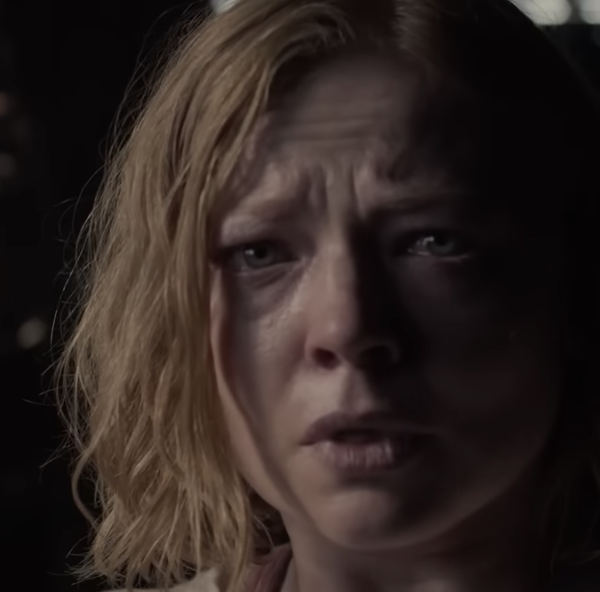

Yet only in a jolting, fiery vision at the end of the movie, in which Nolan briefly envisions an apocalyptic inevitability, does the threat of the movie feel real. (It’s unclear whether this event takes place in Oppenheimer’s head or Nolan’s — but “both” would be an acceptable answer.) Before that climax, Nolan’s filmmaking operates more as a historical fixation on Oppeheimer’s conflicted mindset. As a result, I found the filmmaking thrilling and powerful, but as agitprop, it ultimately comes up short. What about you?

DAVID EHRLICH: I don’t think making “Oppenheimer” function as a piece of agitprop was top of mind for Nolan or anywhere close to it. As you say, the average civilian is already pretty on board with the idea that nukes are bad news, and Nolan’s idea of a political cause is proselytizing about large-format cinema on TikTok. And yet, it is strange that the film doesn’t make a more visceral case against the atomic bomb, particularly because so much is said about the weapon’s function as a spectacle of future deterrence, one whose power could only be accurately conveyed by detonating it for the world to see.

I completely agree with Nolan’s decision to stick with Oppenheimer’s subjective POV and not depict the devastation in Hiroshima or Nagasaki (the scene where a rattled Oppenheimer sits by the radio awaiting news from Japan is one of the most emotionally lucid and upsetting in the entire film), just as I wholeheartedly support his hilariously on-brand decision to shoot the Trinity test with nine zillion pounds of TNT and almost zero CGI. But even in IMAX 70mm, the explosion feels… small.

I’m not saying it wouldn’t wake the neighbors or anything, but if that’s what I saw in the sky above Los Alamos in 1945, I would’ve felt pretty silly about thinking that the bomb might have burned away Earth’s whole atmosphere. Such are the perils of making a movie about a truly unfathomable cataclysm — one that most of us (myself included) can’t quite wrap their heads around even though we’ve had our entire lives to do so.

At the same time, that’s kind of the point. When the United States dropped two atomic bombs over Japan, they left behind enough nuclear paranoia to spark the Cold War, intensify the global arms race, and create a world in which several different countries (nine, at current count) have the power to obliterate entire civilizations at the push of a button. What’s terrifying about “Oppenheimer” isn’t the idea that a bunch of the smartest men on the planet experimented with some plutonium in a cute little town they built for themselves in New Mexico; what’s terrifying is the part where they hand it over to a government full of Robert Downey Jr. types who decided to use it at their discretion, and then decided that the deadliest weapon in the universe wasn’t quite deadly enough for their liking.

I’m on record as being somewhat exasperated by the focus on Lewis Strauss, whose agenda and motivations are gallingly simple when compared to a character as complex as Oppenheimer, but Oppenheimer’s remorse is put into perspective because of the venal men whom he empowers. When Prometheus stole fire from the gods, he ignited a long history of people burning themselves. And — if you’ll permit me to mix my Greek metaphors — Pandora’s box can never be closed. Oppenheimer obsessed over accessing the hidden universe that he saw in his dreams (not that Nolan presents it in such romantic terms), but once he bridged the gap between the worlds of theory and execution, there was no siloing them off again.

As a result of what he and his boys did out in the desert, our species will always live under the shadow of nuclear threat, and we are not to be trusted. That, more than anything, is why I don’t think “Oppenheimer” can really function as a work of “no nukes” agitprop: That apocalyptic ending isn’t a call to arms (so to speak), it’s a surrender to the fact that we might be fucked already. And that is scary to me.

ERIC KOHN: I’m not so sure that Nolan’s throwing up his hands. By virtue of the way “Oppenheimer” imagines our fate, the movie sends a clear message to the audience: This is the risk that humanity must live with so long as nuclear proliferation continues. It’s a visceral expression of the fear that Oppenheimer experienced in his later days and why he was alienated by his community. By resurrecting his paranoia and failings, it basically says: “He failed — will we?” And sure, most moviegoers won’t know what to make of that, but such uncertainty only feeds further into the sense that ambivalence is the greatest enemy against truth.

I also found the Strauss cutaways to be the weakest moments, mostly because they felt like they belonged in a different movie. The core of “Oppenheimer” has less to do with bureacratic red tape and backbiting than the challenge involved in forging responsibility within a self-serving system. While I don’t think the movie goes far enough in condemning the decision to unleash the bomb — Hitler was dead, Japan was losing, come on — I wouldn’t necessarily expect Nolan, a fairly apolitical director throughout his career, to go that far. But I do think he’s trying to utilize film language to make a point about the perilous state of all humanity.

It’s fascinating to consider all this in light of Barbenheimer, which we can’t ignore even in this context as it informs the overall cultural life of “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” as they enter the conversation. Both movies are trying to make profound statements about fundamental flaws that have lingered in society across the ages. One does it in the context of a bright, colorful IP moneygrab as its Trojan Horse; the other lays its ideas bare. It’s true battle of subtext and text. Let’s resolve this once and for all. Which one do you think has the upper hand?

DAVID EHRLICH: You’re getting at the most important Barbenheimer question of all: Which of these two films more compellingly argues that men are bad? In one corner, we have the bright and poppy comic fantasy in which himbo Ryan Gosling tries to annex Barbieland in the name of his fellow bros. In the other, we have the oppressively grim three-hour biopic in which a bunch of pasty nerds build a science camp where they can figure out a way to wipe humanity off the face of the earth, only for their gadget to be co-opted by an even moredangerous group of old white coots who think the only problem with the atomic bomb is that it isn’t big enough (overcompensating for something, boys?).

Based on the “For You” tab of my Twitter feed, “Barbie” would seem to be the clear winner. My iPhone screen is positively teeming with right-wing reactionaries — along with a handful of film bloggers who don’t seem to realize they’ve become right-wing reactionaries — who are convinced that “Barbie” is a “woke” takedown of the unfairer sex, its candied satire merely sugar-coating the message that men should be shot on sight. Meanwhile, the most demented argument I can find against “Oppenheimer” is that Christopher Nolan’s biopic doesn’t go far enough to paint its namesake as one of history’s greatest monster; for these people, it’s simply not enough that the movie ends with Oppenheimer looking into the camera with all the doleful “ruh-roh” energy that a human being can muster.

But leaving the discourse aside for a second, I don’t think we can necessarily reduce this to “a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down” vs. “the bitterest pill of all-time.” I’m so glad that you’ve characterized “Barbie” as a Trojan horse instead of an overt social treatise, because explicit as that movie can be with its messaging (i.e. America Ferrera’s big speech), it has so much going on that not all of it can fit on the surface — or comfortably fit into the story at all.

Sure, it’s an extremely clever riposte against the patriarchy, but it’s also a self-reflexive story about the relationship between reality and cultural representation, a welcome inversion of the idea that little girls model themselves after the women they see on screen, a portrait of capitalism’s questionable ability to criticize itself, and a blistering confirmation of the argument that Michael Cera makes literally every movie he’s in just that much better. Among other things! Is that too much? Probably. But how refreshing that a summer blockbuster will send audiences out into the lobby with a surplus of ideas bobbling around inside their heads.

And even “Oppenheimer,” as we’ve already discussed, isn’t quite as straightforward as it might appear. I think you’re right to identify its alarmist tendencies and question their effectiveness, and I also think you’re right to suggest that the movie should be deemed a failure if we’re grading it on its ability to spur people into action. What action would that even be? All I know is that it will leave people convinced that we’re skating on some very thin ice. Each of these films present a world imperiled by the very forces that it uses to safeguard itself against annihilation (or at least irrepressible thoughts about death), and I think both of them come to the same conclusion by different but similarly effective ways: There’s no hiding from the truth. Whether laughing straight to the gynecologist’s office or somberly staring into the judging lens of history, all we can do is hope to live with it.

“Oppenheimer” and “Barbie” are now in theaters.