Many people have assumed that the 16 millimeter film is an endangered, if not outdated, format. During a surprisingly popular event at this year’s Vienna International Film Festival — aka the Viennale — involved an archaeological search into 16mm’s historical value.

Presented in the Austrian capital, which seems to have more antique stores per capita than any city in the world, the series Revolutions in 16 MM: Towards an Alternative History of the Small Gauge sampled the range and the endless quirks of a format that dominated cinema outside of the studio system from the 1920’s to the 1990’s.

The event also recognized die-hard artists who still work in 16mm – including Kevin Jerome Everson, Jodie Mack, Richard Tuohy, and Alexandre Rockwell. “It’s the beauty, and it’s economical,” said Rockwell, who was at the Viennale with the 16mm-shot “Little Feet.” “Unlike with digital, you don’t pull the trigger so much.”

READ MORE: Darren Aronofsky on Why Digital is Not a Replacement for Shooting Film

The argument might be summarized as follows: 16mm, as boundless as anyone’s curiosity, is an anachronism — and it isn’t. Or, as Marshall McLuhan might have put it, if something ceases to have a function, either it becomes extinct or it turns into a work of art.

Documenting the Past

Making the case for 16mm is like making the case for film itself, since everything from news reporting, to experimental film to pornography was created on the format.

Yet that range is special. 16mm could be shown in a commercial cinema. It was also a format that could be used privately. Hence the extremes that framed the vast scope of the Viennale program.

“It’s incredible what happened with 16 millimeter,” said Hans Hurch, the Viennale’s director. “The whole field of documentary changed completely. Direct Cinema, cinema verite – all these things were made by 16 millimeter, to work with a camera on your shoulder, and to move around.”

He also emphasized the range of productions that benefited from the format. “It was very important for television, and a lot of avant garde films, diaries and private films were made in 16 millimeter,” Hurch said. “And it was a revolution worldwide. We’re trying to document this, but at the same time you see something that’s over, that’s gone.”

Almost gone, that is, to the point that the people who run film archives aren’t always aware of their own holdings in that format. (The New York Public Library has a 16mm lending collection – who knew? Harvard just acquired the Boston Library’s collection, and will continue to loan it out.)

Co-curators Haden Guest of the Harvard Film Archive and Katia Wiederspahn of the Viennale did their own excavation to organize the program, which screened in themed selections.

For critics, that meant watching the films on screens and in theaters – without DVD’s made available to press, and certainly not computer links.

Typical of the Viennale, it was wonkiness in the best sense of the word – scholarly, thorough, projected in a manner that reflected varying states of preservation, and reaching into the depths of film archives worldwide. It wasn’t always easy watching. These were wonks who expected as much from the audience as they do from filmmakers and from themselves. It paid off.

A Range of Possibilities

Programs were more of a sampling then a survey. Even addressing the selective Viennale program in its entirety would be a huge task – an entire section was devoted to war footage, plus one on diary films.

A few of the films point to the program’s heights and to its idiosyncrasies. The 16mm camera gave a new mobility to film without sacrificing image quality. The American docs of the 1950’s and 1960’s combined information and poetry. On the Viennale bill was the classic “Quixote” (1965) by Bruce Baillie, a Whitmanesque collage on American ambitions of conquest that begins with a desolate landscape and winds its way through that territory and through crossfades into the Cold War, eventually arriving at the war in Vietnam. Baillie’s “Mass for the Dakota Sioux” (1963-4) is an epic elegiac requiem for those same places.

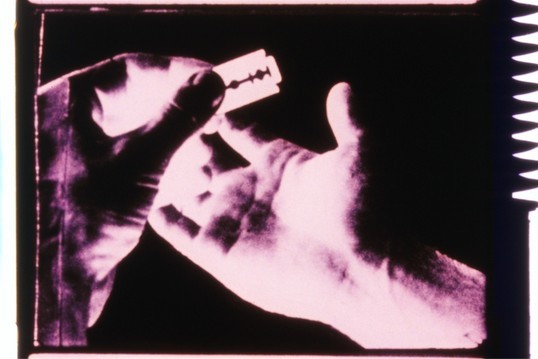

In “Razor Blades” (1968), the manic Paul Sharits — as energetic as Warhol was lethargic — moves in double projection from pulsating geometry to politics and then back to abstraction. The optical effects call to mind the genre called Op Art, an abstract response to Pop Art that conquered the marketplace. Sharits is too much of a satirist to restrict himself to abstraction, playing with all sorts of techniques that Warhol would use, such as colorized portraiture. The cleverly kinetic film doesn’t seem dated today. It could be shown in art galleries, which may be the last places where 16mm films can be monetized.

Revolutions in 16mm reached more topical proportions with “El Grito” (1968), directed by Leobardo Lopez Aretche, which was presented in a program called Collective Cinema. Here was evidence of the global reach of the format – a team of Mexican filmmakers observe the surge of protest at the Autonomous University of Mexico in the spring of 1968. Their cause was to block illegal intervention from the government, which was supposed to remain at arm’s length to ensure freedom of expression — a goal supported by the U.S. until students started taking it seriously.

Framed against a vast plaza in the modernist campus of grand rectilinear architecture, students massed and denounced Mexico’s political leaders, triggering crackdowns by soldiers and police. The filming of it all, as demonstrators made their own political murals and poured across those spaces and onto the city’s broad avenues, was a tour de force of courageous camerawork. The editing for the 101 minute film is a logistical wonder.

Eventually, as the Olympic Games approach in Mexico City months later, soldiers move in to crush the students. We see those confrontations in still images of blood and in drive-by scenes that witness the military maneuvers, filmed secretly by the team to avoid detection. The same bloody streets – now cleared of student – welcome the Olympics.

“El Grito,” which takes its name from the day of Mexican independence from Spain, was banned in Mexico for years. Seeing it on any format was near-impossible, although it has recently been resurrected on YouTube. The version shown at the Viennale had an English voice-over, complete with a section from the journalist Oriana Fallaci’s account of being arrested by brutal police. The print seems to have come from a Mexican archive, thanks to someone who wanted it preserved. Screening it on 16mm was an emotional highlight of this year’s Viennale. It should be required viewing for film schools – even in a digital version.

Home Movies and…Porn?

The practice of collective cinema, a monumental achievement in “El Grito,” takes you into the grey area between trained filmmakers (or students) and absolute amateurs – citizens armed with 16mm.

A program devoted to home movies on 16mm explored those vast DIY depths. Who knew that there were home movies of Joan Crawford? We see her in the 1940’s in color, with a baby who would later inform the world that Crawford was abusive to the children whom she adopted for publicity reasons. Actors are always performing, and we see it here, as Crawford mugs for the camera, dressed for a camping trip in that era’s version of the Ralph Lauren look.

A running joke at the festival was the popularity of the 16mm program devoted to sex. Put a camera in someone’s hand, and sooner or later you’ll get pornography, with as many variants as there are home filmmakers, not always exploiting 16mm to create beauty or even eroticism.

“Deer Hunting,” a U.S. home movie from the 1953 (no relation to the 1970’s Vietnam-inspired heartland drama) was a jolting example. Men who seem to be in their 30’s return from a hunt to hang deer carcasses out to dry, and soon enough, as the beer runs freely, they begin to expose themselves to each other. Everything is game, as one might say, with the dead deer used as props (and silent participants) and a whole range of group positions are explored. Who said the heartland wasn’t kinky? We saw more evidence of that in clips that the curators called “Enema Medley” from 1960-62, where a woman dressed for an erotic experience gave enemas to her husband.

The look was more professional than the home movies, but not much more. Yet even with the tsunami of sexual imagery out there, the efforts in these films to violate taboos about race and sex — even bestiality — might surprise you. In an era when a man and a woman of different races could not rent the same hotel room, there’s a lot going on here – albeit with white men and black women.

The 1922 production “Getting His Goat,” in which three women at a deserted beach decide to take off their clothes ands swim, was particularly striking. They’re unaware that on the other side of a wooden fence, a young man with glasses, dressed as a cartoonish nerd modeled on the bespectacled Harold Lloyd, is ready for some thrills — which he gets through a hole in one of the wood planks. Was 16mm the platform for the first glory hole in film history?

The young man gets his comeuppance when the girls substitute a goat on the other side of the plank, and the man rhapsodizes over the experience. The women get their revenge — a welcome twist, given that era’s gender politics. The film comes with a moral: There’s a sucker born every minute.

More Audiences Await

Each of the Viennale programs on 16mm gave us a parallel universe, much of it previously unexamined. As a whole, the series deserves a wider audience. But the logistics are complicated, the research is demanding, and the films — while abundant — are fragile.

Yet the series suggests that any number of comparable samplings in 16mm could be possible. The repositories are out there. All we need are more intrepid programmers to distill those holdings and project them.

READ MORE: Joel Coen, Martin Scorsese, Darren Aronofsky and More on Digital vs. Film