Considering that it’s the fastest rising sport in the world and that it’s inherently cinematic in a way that, say, baseball isn’t, it’s surprising that Hollywood hasn’t made greater hay out of mixed martial arts (or MMA). For the newcomer, it’s essentially a blend of boxing, wrestling and a good old bar fight, a mix you would have thought would have led to far more movie outings than David Mamet‘s “Redbelt” and next year’s Kevin James (yes, Kevin James) vehicle “Here Comes the Boom.” But a movie opening next month, Gavin O’Connor‘s “Warrior,” which we caught today as the first surprise public screening at Empire Big Screen in London, is planting its feet firmly in the cage, and it’s taking two of the fastest rising stars in town, “Inception” ‘s Tom Hardy and “Animal Kingdom” ‘s Joel Edgerton, in with it.

Tommy (Hardy) turns up on the Pittsburgh doorstep of Paddy (Nick Nolte), his estranged, recovering alcoholic father, after 13 years away. His brother Brendan (Edgerton) is now a school teacher, happily married, in Philadelphia. Their father trained them both to be fighters as kids: Brendan was pro for a while, but never made much of a splash, while Tommy was undefeated, but gave it up when he chose to go with his mother when she fled Paddy’s abusiveness. Tommy finds himself drawn back into the ring to MMA, and soon Brendan is forced, by the threat of foreclosure on his house, to do the same. The two brothers find themselves on a collision course at a big money tournament in Atlantic City described as “The World Series of Mixed Martial Arts.”

Let’s not beat around the bush. “Warrior” is ridiculous. Ludicrous. Virtually every beat is laid out in true sports movie fashion, although the screenplay has to go through some incredibly tortured contrivances in order to get it there; the premise alone is essentially what would happen if Rocky Balboa ended up fighting Rocky Balboa’s war hero brother in the heavyweight championship (after fighting Dolph Lundgren in the semi-final). If you’ve seen one sports movie, you’ll know where it’s going — it’s particularly reminiscent of last year’s “The Fighter,” although without David O. Russell‘s Scorsese-like zip (in fairness, O’Connor’s film was shot almost two and a half years ago, long before “The Fighter” went before cameras). No issue is left untouched along the way: Iraq! The recession! Health insurance! Alcoholism and physical abuse! But god damn it, it works, and works like gangbusters.

The secret of the approach of O’Connor (“Miracle,” “Pride & Glory“) is that however contrived and overblown the plot becomes, he grounds it in reality. And that’s not just the gritty aesthetic, all hand-held and contrast-heavy (DoP Masanobu Takayanagi makes a hell of a Hollywood debut here — you’ll see his work next in Joe Carnahan‘s “The Grey“), but in the characters: their actions are recognizable human behaviors, and it sells even the basic implausibility of the premise.

Furthermore, for all its predictability, the script is capable of shying away from cliche and stays commendably low-key and under-stated. When Brendan tells his wife (Jennifer Morrison, of “House” fame) that he’s off working as a bouncer, when in fact he’s taking low-rent fight gigs in parking lots, you expect that plot line to drag along for most of the running time, culminating in Brendan’s lie being exposed, and an eventual final-reel reconciliation. But in fact, it’s resolved almost immediately, again, in the way that a genuinely happily married couple would deal with such an issue, and it gives a familiar situation some freshness. Similarly, brief hints that Hardy’s character is on steroids are dealt with, something that could have been a full-on sub-plot in a lesser movie.

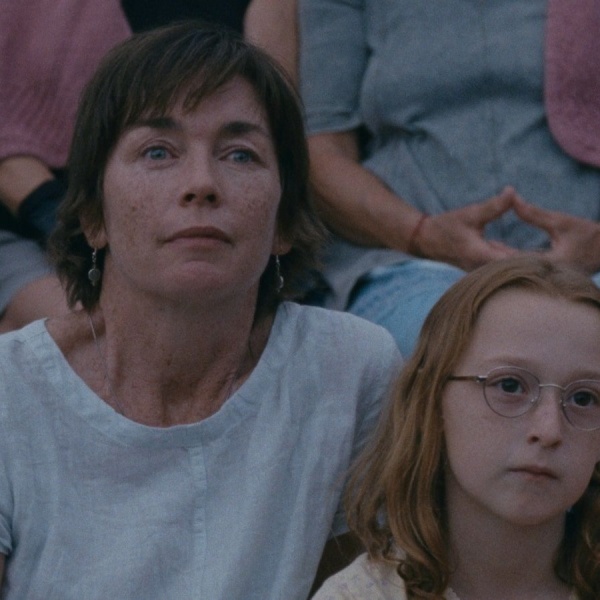

It also helps that O’Connor’s filled his cast with ringers, even in smaller roles. Morrison, for instance, who’s never really had the material to match her talents, takes a part that could have been the “nagging wife” that the type so often becomes, and makes her sexy and three-dimensional; you don’t blame Brendan in the slightest for turning his back on his family for her. Frank Grillo, meanwhile, shines as Brendan’s trainer, another could-be-archetype given a new lease of life by injecting a fierce intelligence; it’s suddenly obvious why the actor is becoming omnipresent (and he’s just landed a role in “Gangster Squad“).

Contrary to some buzz that we’d heard in advance, Nolte isn’t quite hitting his career best (try “Mother Night” or “Afterglow“), but he is very, very good as a man desperately trying to make atonement, no matter how pathetic it might make him. But the director’s real coup is in his leads, both cast long before their current surge onto the A-list. Hardy, once more built like the proverbial brick shithouse, is a world away from the flamboyance of “Bronson” and the charm of “Inception” — it’s a fiercely insular turn, a man being eaten away by self-loathing and self-destructive tendencies, but still very much the younger brother: there’s a lovely gentleness and sweetness to an early interaction with a waitress, for example.

And Edgerton fully lays down his cards as a potential leading man. It’s canny of O’Connor to introduce his lead (and make no mistake, it’s Brendan’s story) while wearing a bonnet, plastered in make-up by his daughter — it emasculates the character in a testosterone-driven world so much that it makes his transformation all the more impressive. Watching Edgerton’s journey from doughy family man and schoolteacher to lean, mean elbowing machine is like watching Russell Crowe‘s performances in “The Insider” and “Gladiator” back-to-back. It helps, too, that their chemistry, even in the handful of scenes they share, is strong, instantly establishing a lived-in sibling relationship that shorthands decades of hurt. It also helps that the pair are never less than totally convincing as pugilists.

And those fights! It’s been tricky since “Raging Bull” to find a new language to shoot screen fights (“The Fighter” tried a bold approach, but one that rather undermined the dramatic potential of the scenes), but O’Connor seems to have nailed it. He’s not doing anything particularly radical, other than introducing a new twist on competitive scrapping to the screen. But he’s got a real eye for the detail of the ritual of battling, and every one of the (many) punch-ups are visceral, clear and extremely well-cut — the final scene in particular is almost unbearably intense. And, when the release comes, deeply, deeply moving (this writer has to confess he had something in his eye as credits rolled…).

There are plenty of things wrong with the film. Some sub-plots, like one involving the principal of Brendan’s school (Kevin Dunn), seem like nothing but padding. Mark Isham‘s score is about as treacly and heavy-handed as you’d expect from the man who wrote the music to “Crash,” “Bobby” and “Crossing Over.” The screenplay is more often than not a little exposition-heavy, most notably in the real world UFC commentators whose job in the third act seems to be to reiterate every important piece of information.

But really, the film’s blue-collar tale is something like the filmic equivalent of a Bruce Springsteen song (the film is bookended by a pair of songs by The National, who are in some ways a successor to The Boss). And not a subtle, darker, late-period track, but a balls-out anthem like “Born to Run.” You might have known it off by heart for the majority of your life. You might groan when someone puts it on the jukebox, or when you hear it on drive-time radio. But when you hear it played by the E Street Band at full volume at Madison Square Garden, there’s no denying a certain artistry to it, and it’s almost impossible not to sing along. [B]