When young John McGill (Conor McCarron) scores a 100% score at the start of “NEDS,” the grade-schooler quietly rejoices in his seat, proud to have distinguished himself from his peers. His reward? He is singled out by his snooty instructor for being a “swot,” a sarcastic congratulations for his “embarrassing” score is the beginning of his ostracizing.

“NEDS” begins innocently, with the cherub-faced John hoping to one day become a journalist, emerging from his lower-class Scottish surroundings, escaping the glare of his stony-faced, alcoholic father (Peter Mullan). It’s the unexpected indignity of his early success that shapes the boy. Ridiculed at school for the skills he originally found worth celebrating, he finds solace in dropping to the mean, so to speak.

It’s his legacy that saves the boy’s life. When threatened with violence, his trump card is his estranged older brother, a local gang member. We don’t know the boy’s crimes, but when a threat to John becomes an offer to buy a sandwich because of his bloodline, we are to assume his brother made more than a few connections.

And so school, an oppressive place where children are wrapped on the hand with leather straps for “impudence,” becomes a distant memory for John. He ages into his teenaged years as a thick brick of a boy, a hard-faced bruiser whose youth is only recognizable by his chubby red cheeks. A future as a journalist in America is no longer even considered, as the boy’s angry brawling becomes a daily activity. It’s clear he hasn’t learned to reconcile how his individualism was treated by others: when a bully from years ago attempts entrance into the boy’s crew, John gives him a clear reminder of the past. It’s not exactly a friendly sit-down.

“NEDS” effectively avoids the cliché of the coming-of-age story where youth-meets-criminal lifestyle because director Peter Mullan has a solid handle on the realities of this boy‘s life. There’s a vicarious thrill in John’s early misbehavior; it’s only natural to laugh when John smirkingly demands more leather abuse from a teacher. And when John escapes the beating of another gang, he ends up in the home of one of his pursuers, having tea with their mother. Though John has grown to be brutish, he has retained his sharp social intelligence of his youth, not to mention his sly sarcasm.

Of course, these aren’t the gangs you may be familiar with from previous youth-gone-wild movies. There is no material wealth to be gained from forming such a union in this culture, and John’s reward is merely that he no longer stands out. Of course, he doesn’t want to just be a part of something – the boy wants to be a leader as well. It’s not a question of if it will end well for John. The question is, how poorly?

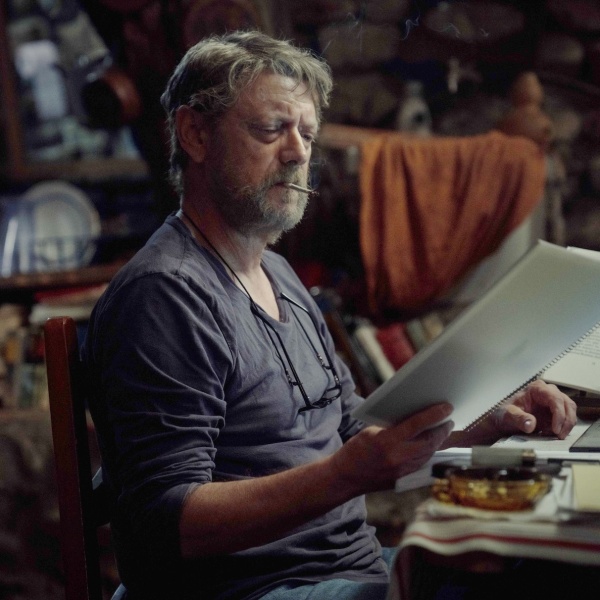

Mullan recasts John from his youth to his teenage years in order to cement the idea that the educational system has killed the youth, leaving behind the bear-like delinquent we see here. John is now a Non-Educated Delinquent, and as a NED, his adventures initially have a boys-will-be-boys vibe. The shift to a more dramatic perspective is handled swiftly, but some of the impact is curtailed by John’s shadowy father, who emerges late in the narrative with a major role despite the audience’s lack of awareness as to how much he shaped the boy. It isn’t until the start of the third act that we see them interact in any way, as we are meant to assume early on that he is a regular at the pub, forcing his wife to accommodate his drunken commands for late night attention while John lies in bed. The narrative takes an ungainly shape when Mr. McGill becomes a major player, as his last-act prominence is meant to be a catalyst for revelations on John’s evolution. We need to learn about John’s father before we fully understand what John has become.

Despite this misstep, Mullan remains commanding as the defeated, self-loathing father, silently acknowledging that he has a twisted respect for his son, clearly flaming out at an early age. The man hurts, he is bruised, and he seems to be the only one understanding the gravity of the situation. Mullan, an experienced writer-director-actor, doesn’t necessarily want you to hurt like he does, but in “NEDS” he compellingly illustrated how institutionalized cycles of hatred and violence aren’t alien to everyone. [A-]