The stories of Adam Sandler as a generous superstar are numerous. In addition to his charity work and what’s said to be a personable demeanor (amongst those the protective star allows inside), there’s no doubt he’s been loyal to both his fanbase and friends. Nobody, including the scandal-happy tabloids, seems to ever have a bad thing to say about the comedian that continues to top the box office for almost 15 years now.

And then, there are the movies. Lazy, unfocused, poorly-made paeans to arrested development, condescending tributes to the middle class, peppered with an attitude of sexually and racially obtuse mockery that ignores the basic humanity of acceptance in favor of thuddingly-dull destitute-man’s Capra theatrics. Sandler’s films are filled with a curious sort of affection, in that they flatter the dimmest of audience members.

Optimism suggests that perhaps Sandler bottomed out with “Grown Ups,” a laborious summer vacation posing as a movie where his peers wasted time making dick jokes and mocking each others’ quietly upsetting suburban ennui. And perhaps he did. “Just Go With It,” from the same director (Dennis Dugan) has slightly more energy and vitality that the deadening “Grown Ups.” To be charitable (and for those that crave brevity), this is probably an average Sandler joint.

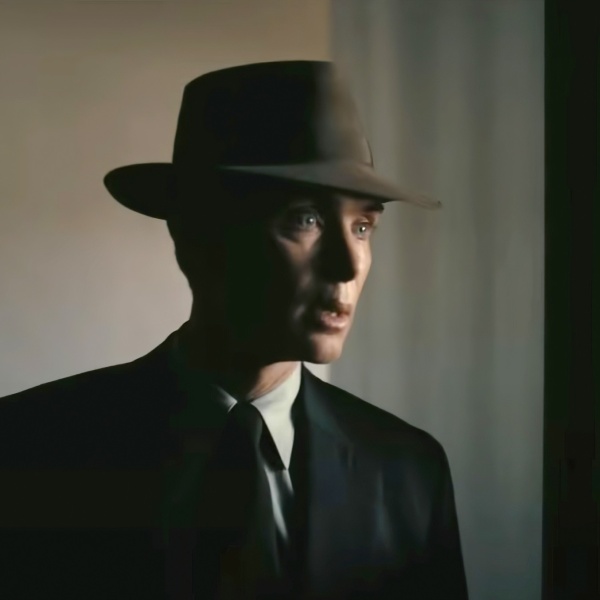

Which is to say that the picture is par for the course as far as Sandler’s output when it comes to casual sexism, racism and homophobia. “Just Go With It” begins within the prologue, with Sandler with a Cyrano-like beak, listening in on his soon-to-be wife bemoaning his inadequacies in every field. As he runs from the altar, he channels this self-loathing into not-so-guilty sex, as the wedding ring he still wears proves to be an aphrodisiac to any woman who crosses his path. Twenty three years of ugly, dishonest casual sex (sans nose), he still wears the wedding ring, operating as a bachelor out of his plastic surgery practice. Normally, it would take a lot to get the audience on the side of someone fairly deplorable, but for Sandler all it seems to require is a nebbish idiot smile.

Attending a beach-side party for a few of his clients, he meets a young schoolteacher who, charitably, seems about half his age. He falls for her quickly, though that may be a result of the camera lingering over her bust, watching her blond hair blow in the wind. Brooklyn Decker, probably a sweetheart in real life, is dressed and photographed just like the extras in all of Sandler’s films: it’s a curious trademark, that Sandler would constantly feature in films where superficially-beautiful white women wear tacky clothing and traipse around in slow motion for the camera to ogle. Credit to the casting director, who manages to quietly slip the odious Heidi Montag into this scene despite her looking like every other woman onscreen.

Sandler makes a deep connection with this girl as they spend the night gazing into each others’ eyes. This is conveniently offscreen, the better to accept what she would see in such a lumpen fugazi of a man, and what sort of conversation this transparently one-dimensional character might have with a plastic surgeon. Sandler’s films don’t bother with the details of human interaction — why waste time showing real people making an actual connection when you can shoot enough footage in your two hour (no, really) movie of Nick Swardson humping a sheep? She does discover his fake wedding ring, however, and she flees immediately, the last time that character will show a shred of self-awareness.

Determined to no longer use the ring as a crutch, Sandler decides to cook up an elaborate lie the very next day, despite having plenty of time to think of something workable. Somehow, she buys that his ex-wife “Devlin” has been cheating on him with a “Dolph Lundgren” (and not THE Dolph Lundgren) and that he is free to see other people. When she insists on meeting Devlin, Sandler enlists his receptionist and longtime friend to play the part.

Of course, it says a lot about Sandler’s puerile views on sexuality and Hollywood’s treatment of women that the luminous Jennifer Aniston is viewed as dowdy best friend material. When he recruits his longtime ally (whom he has an obvious chemistry with, maybe a first in the Sandler canon), we finally see what casting directors have been catching in this actress, stuck doing thankless work playing Reaction Shot to a number of prestigious comedians. Mostly due to nearly a decade of sitcom work, Aniston has sharp comic timing, and whenever Sandler lets out one of his typically sloppy put-downs, she volleys back quickly. In a brief scene where, performing as his fake wife, she has a quip about his physical inadequacies for every meandering comment he makes, Sandler almost disappears from the screen.

Somehow, this web of lies extends to a trip to Hawaii, where Sandler attempts to charm the pants off the nubile Ms. Decker, Aniston in tow with her two sitcom-trained children as well as Dolph, manufactured entirely by the sub-moronic Swardson. After the deceit stretches to unmanageable lengths, the film simply feels cruel in how it treats Ms. Decker, somehow oblivious to the obvious truth. Despite her schoolteacher status, the film seems completely uninterested in giving her an inner life, making Sandler’s second-guessing of the entire arrangement completely free of actual drama. It seems most offensive that she can’t seem to realize that Swardson’s Dolph, a khaki short-clad “sheep-seller,” isn’t an embarrassing ruse on its own.

It’s her virtues that seem odd as well. She barely knows him but agrees to meet his family and head to Hawaii. There’s the brief suggestion that she’s promised sex that hasn’t yet happened, and yet she seems completely fine with the possibility that he may be considering marriage. Granted, there’s nothing wrong with prolonging sex, or waiting until marriage, or eloping after only a couple of weeks. But in this film, we never know why she makes these decisions. It is a Sandler movie and she is a woman, so the reason is probably because she’s a prop.

For those curious, Nicole Kidman pops up as Aniston’s old college nemesis. It’s the sort of thankless role you’d see someone like Juliette Lewis try, so it’s a little strange to see the still fairly-intense Kidman trying to let loose, matched up with the deadweight of Dave Matthews as her obviously gay husband. A dance contest between the two is meant to slowly up the ante, but it’s hard to believe Kidman as a woman slowly becoming obsessed with beating Aniston when she has that iron-melting stare for the entire film.

As befitting its title (and a climax set ENTIRELY offscreen, surely some sort of first), “Just Go With It” is an entirely lazy affair, yet another in that curious subgenre of people conceiving of increasingly absurd lies to become somewhat attractive. What’s interesting is that Aniston’s receptionist falls hard for Sandler after more than two decades of a sex life built on deception, and that’s AFTER being used as a verbally-abused plot device to make him attractive to someone else. Is the argument that romance is dead because movies like this are made? Or are you killing romance by paying money to see it? [D-]