From our reviews correspondent over at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival, James Rocchi.

Martha (Elizabeth Olsen) wakes up in a crowded farmhouse in rural New York — and runs across the road and into the trees. The woods are lovely, dark and deep, and Martha has promises to both keep and break. And like that, we’re hurled into Sean Durkin’s harrowing, gorgeously shot psychological drama — one of the standout films of Sundance 2011, and a stunningly strong debut. Martha reaches out to her sister Lucy (Sarah Paulson), and despite not having heard from Martha in two years, Lucy comes to get her with the sound of both sympathy and judgment in everything she says. Taken in by Lucy and her husband Ted (Hugh Dancy), Martha can’t quite bring herself to tell her sister exactly where she’s been and what she’s been doing, even as it becomes harrowingly clear that Martha’s life for the past two years was far from ordinary — and may be far from over. The film’s title combines all the names Martha’s been known by, or given, or has given, in her recent past — and that shifting, unfixed confusion defines the terrors and tones of the film.

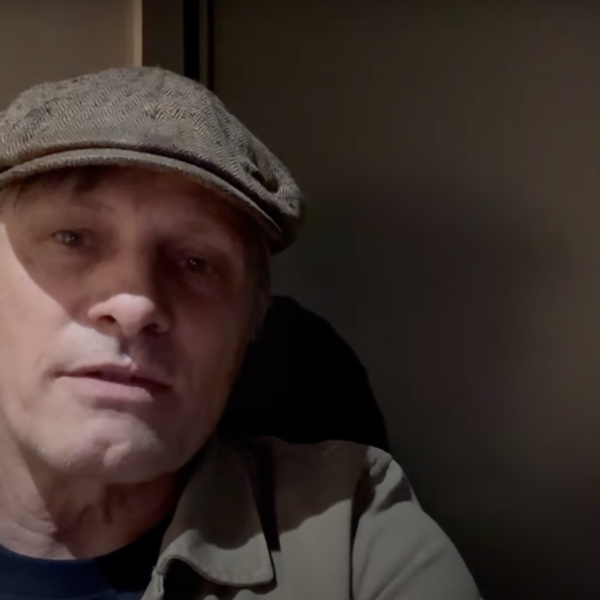

Flashing back, Martha’s past becomes partially clearer to us even as it’s kept from Lucy. Martha, lost and adrift, found a commune and a community, led by Patrick (John Hawkes). And the communal effort and shared meals are revealed as something much more cruel and complex as we witness what Martha had done to her — and, worse, what she herself did. Durkin’s interested in exploring cults, and cults of personality — Hawkes has the charisma and temperament of an Old Testament scion — but he’s also crafted a subtle, insidious film about identity and trauma that forgoes over-explaining things in favor of a mood, and mystique, that sinuously worm themselves into your brain as you watch.

Olson’s performance is amazing — much is asked of her as an actress, and much is given. Martha’s unable to explain what exactly happened to her — and Lucy at first thinks she’s simply been off on a journey of post-adolescent angst. And Martha’s briefly able to put up a brave front that everything’s fine until the real nature of the past two years cracks through the façade of normalcy. There are elements in her performance that sound, on paper, like indie-film clichés — nudity, sex, harrowing emotional breakdowns — but Olson makes them part of an organic, living performance, and your attention is riveted by the sadness and worry playing silently across her face throughout much of the film.

Jody Lee Lipes’ cinematography and Zac Stuart-Pontier’s editing work hand-in-hand to create Martha’s world — and also convey the fluid flicker as her past leaks into her present. We always know where we are in the timeline of the film, but the membrane between past and present is so permeable, so thin and delicate, that we become partners in Martha’s confusion. The score by Saunder Jurriaans and Danny Bensi is also a highlight of the film, electronic droning and slow notes reaching crescendos of intensity that become almost unbearable before snapping back to a silence fraught with the tension of what can happen next.

Paulson does excellent work as Lucy — comfortable, clueless, and yet more than willing to listen to the little Martha is able to convey to her. But Hawkes, a year after another riveting Sundance performance in “Winter’s Bone,” is fascinating and haunting as Patrick. A manipulator, a cult leader and a charmer, Patrick is capable of incredible grace (singing a song of love to Martha in front of the commune) and terrible brutality, and his quiet contemplation is just as grim as his shouted fury. (When Martha acts out, Patrick’s response is a masterwork of manipulative game-playing: “Maybe I asked too much of you too soon; I’ll expect less of you from now on. …” )

“Martha Marcy May Marlene” is superbly acted and assembled, but it is also entirely terrifying, and deeply disquieting, building a mood of paranoia with both intense, brutal transgressions and small, creepy touches of tone. The commune’s telephone — with instructions and procedures for dealing with callers scrawled on the wall around it — is a moment of set design that chills with unexplained implications. A series of home burglaries play out with brazen calm that turns far more intense. And Martha, ostensibly safe with her sister, can’t tell if the cult is still in her life or just still in her head — and neither can we, and we find it equally hard to determine which would be worse. Superbly crafted, stunningly well-acted and more than willing to let our imagination fill out the spaces in its gorgeous shadowed darkness, “Martha Marcy May Marlene” is a film of haunting beauty that marks Durkin’s arrival as a subtle and strong director to watch. [A+]