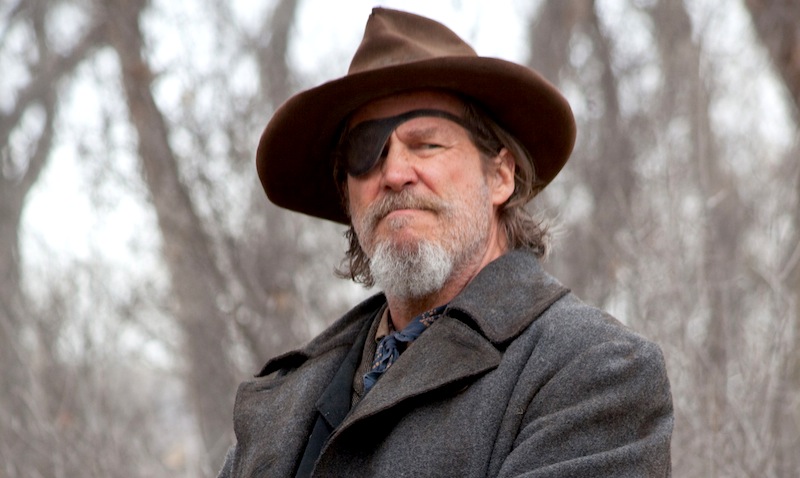

There are two genres that every filmmaker wants to tackle: the musical and the western. Having flirted with the latter a number of times, the Coen Brothers, undoubtedly one of the foremost filmmaking teams of their generation, have finally delivered their first full-flung oater with “True Grit,” a second adaptation of the Charles Portis novel made famous for winning John Wayne his only Oscar the first time around.

The Coens’ “True Grit” is something of a triumph in general, but perhaps the biggest surprise is how traditional the film feels — there’s little post-modernism or revisionism in there, and you feel that even The Duke himself would have approved. With the picture hitting theaters today, we decided it was as good a time as any to take a look over the most American of genres.

If we’re being honest, this list could have run to double the length (and we may yet follow it up with a part two) — the western is one of the oldest archetypes in cinema, even if it’s fallen out of favor in recent years. As ever, we’ve tried to re-examine some terrific pictures that are overlooked these days, but there are a few stone-cold classics that we couldn’t resist writing about too. It’s by no means comprehensive, but if “True Grit” gets you itching to revisit the Old West over the holidays, these are some good starting points.

“The Ox-Bow Incident” (1943)

“The Ox-Bow Incident” (1943)

Playing rather like a nihilistic Western version of “12 Angry Men” (complete with a conflicted Henry Fonda) if “The Ox-Bow Incident” had been made now, we would probably accuse it of being a too-on-the-nose analogy for U.S. involvement in the War on Terror. But it was made in 1943, and as the prominent War Bonds advertisement displayed at the end of the print we saw attests, it’s really talking about a different war altogether. However, that it is a parable about mob rule, the dangers of someone’s-gotta-pay mentality and the immorality of never suspending the rule of law EVER, is in no doubt — this rather talky film was clearly made to teach us a lesson. And aside from a strangely episodic first third, it does that extremely well — the simple story of an illegal posse who ride out looking for revenge and end up exacting it on the wrong people, still has the power to make the blood boil. Featuring early standout performances by Dana Andrews and Anthony Quinn, this largely forgotten film should be required viewing for anyone thinking of, I don’t know, denying person X’s civil liberties or torturing person Y in the “national interest.” [B+]

“Shane” (1953)

“Shane” (1953)

An all-time classic of the genre and Alan Ladd’s finest non-noir hour, this film is a summary example of how telling a familiar story from a different angle can make it feel completely fresh. The story: an ex-gunfighter happens into a job on a farmstead where his respect and love for the family he joins ends up driving him back to the life he was trying to escape, in the ultimate act of self-sacrifice. The angle: it’s mostly told through the eyes of a child. Somehow the naivety and black-and-white innocence of little Joey’s hero worship makes Shane’s choices all the clearer, and all the harder too. Stakes? It’s got ‘em in every single scene, making “Shane” a riveting and truly touching watch. Aside from “The Dirty Dozen,” this is one of the few films that men are officially allowed to cry at with no ensuing loss of masculinity. [A]

“My Darling Clementine” (1946)

“My Darling Clementine” (1946)

Director John Ford’s take on one of the most notorious stories of the frontier era — the gunfight at the OK Corral — is notable today not just for being marvelous entertainment, but also for inspiring other directors. Most impressively, Sam Peckinpah, himself no slouch in the western department, cited it as his favorite film in the genre. And indeed, there are times here when what you’re watching is no less the establishment of genre archetypes — low angles picking out the Earp brothers from far away through the deserted town, or the utterly iconic shot of Wyatt (Henry Fonda) alone and fearlessly centered mid-frame as he walks deliberately to the showdown. Taking immense liberties with the real story, Ford’s version still somehow feels definitive and the almost-a-buddy-movie arc of the central characters Earp and Doc Holliday (Victor Mature) has never felt fresher. ”Tombstone” it ain’t. [A-]

“The Ballad of Cable Hogue” (1970)

“The Ballad of Cable Hogue” (1970)

Consider us a little more than shocked when it was discovered that Sam Peckinpah’s personal favorite was not the unbelievably well-edited “The Wild Bunch” or the tense thriller “Straw Dogs,” but the bouncy comedic tale of an abandoned middle-aged man who exploits his discovery of water in the desert. It makes sense considering its successful experimentation, including abrupt tone changes and an abandonment of traditional narrative. There’s not much in terms of action, instead are plenty of amusing vignettes and fan-service courtesy of a perverted reverend, but not all of it works. It’s also his most romantic film and the titular character is played by the excellent Jason Robards, ever so lovable and able to ground things when the comedy gets a bit too silly. [B]

“Django” (1966)

“Django” (1966)

Even though things are a bit dull until about halfway through (save for the always-amusing ear dismemberment and the subsequent ear snack), once “Django” hits its stride, it never lets up. Frank Nero (in a Man-With-No-Name attitude) saves a prostitute from being killed by not one gang of corrupt men, but two, and rides her into the adjoining ghost town where only a bar/brothel survives. It’s soon discovered that he wasn’t just out getting Vitamin D: the man who is responsible for the death of his wife, Major Jackson, operates in the area. Even though he walks a mysterious coffin like a pet dog, interest in the secret wears thin and the reveal, while totally badass, only leads to a disappointing 30-second action scene. Nero doesn’t have the power or immediacy to carry the feature through its many extraneous expository dialogue scenes, but once the director throws him into large action set-pieces, such as the raid on a Mexican army fort, energy is high and Nero holds his own. Chances are you’ve seen the similar and superior “A Fistful of Dollars,” but those who stick it out will eventually be pleased despite its inconsistency. Special recognition goes to the final scene, which is both excruciatingly tense and rewarding in its pay-off. [B-]

“Unforgiven” (1992)

“Unforgiven” (1992)

It seems that one’s appreciation for “Unforgiven” largely depends on when you saw it. The hype surrounding the film will serve to disappoint anyone who catches up with it later, but it doesn’t diminish the fact that the film is a contemporary oater and revenge flick of the highest order. The film follows aged, widowed outlaw William Munny, a notorious gunslinger who is now spending his autumn years raising his two kids on a pig farm. One day he receives an offer from a young whippersnapper, The Schofield Kid (Jaimz Woolvett; whatever happened to that guy?) to join him to collect on a bounty put up by a group of prostitutes after one of their own was cut up by a cowboy. Munny initially turns him down, but then reconsiders, locates his old partner Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman) and together with the trigger happy Schofield Kid, set out do the job. But the gang soon run afoul of Sheriff Little Bill (Gene Hackman) who doesn’t allow guns or assassins in his town. The brilliance of “Unforgiven” lies in the script by David Webb Peoples, who puts his hero at a moral crossroads: engaging in the same reckless, wanton violence of his youth that he now regrets, but doing so because it’s the only way to set things right. This is a western that lingers on the consequences of pulling the trigger and taking a man’s life (a sequence set in a canyon where Munny and Logan grow disgusted while watching one of their targets suffer is an eye-opener). And while the moral complexity is wiped away thanks to a guns blazing climax that doesn’t quite jibe with the film’s undertones, Eastwood has created a contemporary classic, rich in character and atmosphere with an almost Sam Peckinpah-esque grim consideration that sometimes violence is the only answer a man has. [B+]

“The Quick & the Dead” (1995)

“The Quick & the Dead” (1995)

Sam Raimi took an “all killer, no filler” approach to his lone western, the streamlined tale of an annual gun-slinging competition in the ominously named town of Redemption, and the lone woman (a badly miscast Sharon Stone) brave enough to enter. The movie is high on sizzle, both with its who’s-who line-up of character actors in supporting roles (including Keith David and Lance Henriksen, as well as soon-to-be superstars Leonardo DiCaprio and Russell Crowe) and its emphasis on visual style over narrative coherence. That said, it’s all really, really fucking cool, especially when Gene Hackman is on screen, devouring scenery as the corrupt sheriff who, many years prior, killed Stone’s father (played in a fleeting cameo by Lt. Dan himself, Gary Sinise). [B]

“El Topo” (1970)

“El Topo” (1970)

Alejandro Jodorowsky wrote, directed and starred in this trippy western (reportedly John Lennon’s favorite movie), as a gunslinger in a quest to become the west’s finest killer. In the process, he guns down a series of memorable avatars of violence, only to be betrayed by his own lust for power, reborn in a small town as a pacifist circus performer, unaware that his now-grown son seeks revenge for his abandonment. “El Topo” is a surrealist spaghetti western that takes aim at the hypocrisies of violence and religion, with unforgettable sequences that showcase a filmmaker in Jodorowsky that, with his second picture, was definitely one to watch. A must-see for anyone who likes their westerns experimental and off the beaten path. [A]

“Forty Guns” (1957)

“Forty Guns” (1957)

Beloved by the French New Wave much like Nicholas Ray, Sam Fuller is best known for Criterion-approved works about damaged freaks like “Shock Corridor,” “Naked Kiss” and “Pickup on South Street,” but his 1957 CinemaScope-shot western starring Barbara Stanwyck, Barry Sullivan and Gene Barry is not too shabby either. While it’s his second western after “I Shot Jesse James” (“Baron of Arizona”is technically more of a land-owning drama), we still prefer this picture, which chronicles the life of a tyrannical rancher (the great Barbara Stanwyck, natch) who rules an Arizona county with her private posse of hired guns. An avowedly peaceful U.S. Marshall (Sullivan) who has never fired his gun arrives to restore order to the local town, but while he’s setting things straight and messing things up for the despotic queen, she starts falling for him. Things get ugly and complicated later on (a bride actually gets shot in the head during a wedding ceremony for christ’s sake!), so while slightly uneventful in its first half, “Forty Guns” becomes more engaging as the film progresses. And Fuller makes the most of his widescreen format, shooting wonderful close-ups and impressing every auteur in France with one of the longest tracking shots in history up until that point. [B]

“Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid” (1973)

“Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid” (1973)

Sam Peckinpah’s glorious return to the western, his first since “The Wild Bunch” (OK, there was “The Ballad of Cable Hogue” which was atypical), was not so glorious. Plagued by production woes, reshoots, battles with studio honchos, and finally, having the final cut taken away from him, it’s only thanks to the DVD era that we can see what Peckinpah originally intended, and while it’s certainly not a perfect film, it’s definitely one-of-a-kind. The plot, what little of it there is, has newly hired lawman Pat Garrett (James Coburn) tasked with taking out Billy the Kid (Kris Kristofferson) on behalf of a bunch of cattle barons. And then a two-hour, meandering chase ensues. There is no surprise that the film ran over budget and schedule as Peckinpah seems to have been making it up as he went along and really doesn’t have much to show for it. Yet, despite its rough-hewn composition, there is a lot be charmed by. Kristofferson gives one of his career best turns here as the undeniably affecting Billy and though he’s relegated to few lines and largely a lot of window dressing, Bob Dylan is surprisingly solid as the mysterious, enigmatic knife wielder Alias who mutters lines just as cryptic as Dylan’s lyrics. And oh yeah, that great score? By Bob Dylan as well. There are flashes of brilliance through the picture, and lord knows Peckinpah can shoot the shit out of a landscape, but it’s not quite the lost masterpiece some would claim in latter day reassessments of the film. That said, it still stands as a unique genre picture, one marked with enough quirks and left field moments to make it a must see for any Peckinpah fan. [B-]

“Johnny Guitar” (1954)

“Johnny Guitar” (1954)

Of all the great Nicholas Ray works — “On Dangerous Ground,” “They Live By Night,” “In a Lonely Place,” “Bigger Than Life” and a little film called, “Rebel Without a Cause” — the director’s second foray into the world of westerns with 1954’s, semi-campy and technicolor (actually “Trucolor”) “Johnny Guitar,” is not his best. It’s pretty damn strange in tone for a western, with its bright reds and lustful, romantic innuendos (of course the French loved it and Truffaut, a devout Ray fan called it the “Beauty & The Beast” of westerns). But with the twosome of Joan Crawford and Sterling Hayden in the leads, it is mostly watchable and entertaining. Crawford plays a strong-willed western woman-type (it could only really have been her or Barbara Stanwyck) who builds a saloon outside of an Arizona town, hoping to expand when the railroad comes through. But she is not welcome, especially with bullish rancher Emma (Mercedes McCambridge), when along comes the guitar-strumming drifter (Hayden)… if it sounds like the ingredients for a soupy melodrama, well, that’s kind of what it is. Apparently McCambridge and Crawford’s onscreen animosity boiled over into real life which adds a nice level of antagonism to the proceedings, adding to the heady brew that is this curious and unusual mix of woman’s picture and genre western. [B]

“Rio Bravo” (1959)

“Rio Bravo” (1959)

The great Howard Hawks may have been the Steven Soderbergh of his day; a master technician adept in any genre, in any field, known for his immense versatility in any setting. He made classic films noir (“The Big Sleep”), rapid-fire whipsmart screwball comedies (“His Girl Friday,” “Bringing Up Baby”), comedic musicals (“Gentlemen Prefer Blondes”), sturdy war films (“Sergeant York”) and of course, westerns (the brilliant “Red River” deserves its own entry as well). Featuring an all-star cast of John Wayne, Dean Martin, Ricky Nelson, and Angie Dickinson, it’s hard to go wrong with this somewhat innocuous — shot in a lot of toothless master shots — but still ever-entertaining western about a lawman (Wayne) and his disgraced, drunkard ex-partner (Martin) trying to hold onto a worthless but well-connected prisoner (Claude Atkins). Wayne looks to be facing his foe all alone until his drunken deputy pulls his act together and a young, arrogant gunslinger (Nelson) joins the fray and helps even the odds for the inevitable final showdown, making this as much a buddy picture as it is a western. One of the lightest entries on this list, the violence never threatens to reach a level where you think anyone is at risk of dying, but it’s still enjoyable, and it’s amusing to watch Hawks shoehorn musical numbers into the film because Nelson was a young pop sensation hearthrob at the time. [B]

“Stagecoach” (1939)

“Stagecoach” (1939)

Known as one of the greatest westerns of all time in the year that yielded some of the greatest films of all time (1939; “The Wizard of Oz,” “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” “Ninotchka”) John Ford’s “Stagecoach,” follows in the long line tradition of disparate motley crew travelers on the road towards adventure archetype. Nine travelers board a stagecoach on the road to Lordsburg, New Mexico. It might be one of the kookiest groups ever assembled since Frodo went on his quest. There’s the Marshall (George Bancroft), his whiny idiot stagedriver (Andy Devine), the wimpy wuss whiskey salesman (Donald Meek), the Republican asshole banker (Berton Churchill), the philosophical drunk doctor (a wonderful Thomas Mitchell), the prissy lady (Louise Platt), the unctuous Southern gentleman gambler vying for her affections (John Carradine), the town whore (Claire Trevor) and Ringo, a good-hearted fugitive they find on the road forced to join the gang with the full knowledge he’ll be heading to jail afterwards (John Wayne). The problem is they’re in Apache country, the U.S. Army is nowhere to be found and they have no choice but to forge on making for one of the most thrilling sequences in cinema ever made when the stagecoach tries to cross the desert and is attacked by those crazy Injuns. The fellowship dissolves as they reach their destination and after flirting with the idea throughout, “Stagecoach” blossoms into a romance between Wayne and the street hussy only he will love. It’s pitch perfect, economic and flies by. In case you think westerns are dull (you twee-film-loving dummy), this one is not only in the National Film Registry and an AFI top 10 western, it’s Criterion approved. Cranky old Ford wouldn’t give a shit either way. [A-]

“The Naked Spur” (1953)

“The Naked Spur” (1953)

Forget the unlikely-friends-on-a-mission western of the original Henry Hathaway “True Grit” (boring, the Coen Brothers’ version is significantly more awesome), Anthony Mann’s “The Naked Spur” is where it’s at for this niche-brand of cowboy film. In fact, it’s not a drastically different story and centers on a bounty hunter (Jimmy Stewart) trying to bring a murderer to justice (an awesomely slimey Robert Ryan) who is forced to accept the help of two less-than-trustworthy strangers — a grizzled old prospector (Millard Mitchell) and a handsome and younger, but disgraced Union lieutenant (Ralph Meeker). All three men capture the criminal only to find him with a young wayward woman (Janet Leigh). The trio then attempt to bring the cutthroat in, but the oily man tries to turn the unlikely crew against each other with greed-led psychological games. The drama intensifies along the way, building to a savage climax that is worthy of the Coens’ violent conclusion to their Charles Portis re-do. Gripping and absorbing, a box-office hit — screenwriters Sam Rolfe and Harold Jack Bloom were nominated for an Academy Award — “The Naked Spur” didn’t receive its due as one of the best westerns ever made until recent years. [A]

“The Searchers” (1956)

“The Searchers” (1956)

Dubbed the “Greatest Western of All Time” in 2008 by the AFI, it remains easy to see why fans of this film can make such a definitive claim. Thematically complex, morally ambiguous, set against sprawling widescreen vistas, spanning years and subplots with epic grace, directed by acknowledged western guru John Ford, and starring the genre’s most iconic actor, John Wayne, frankly “The Searchers” just fucking rules. A relatively late entry into his western canon, much of the fascination comes from watching Ford, who is more than anyone responsible for the mythology of the movie western as we understand it, delicately unpick the fabric he had so carefully woven up to that time: “The Searchers,” with its (albeit tentative) exploration of racism and the genocide of the Native American population, is a revisionist western before revisionism happened. And Ford coaxes out what is perhaps John Wayne’s finest performance, where he too subverts the man’s-man hero he had played a million times and embodies Ethan Edwards as a character tortured by his own bigotry and constantly at war with his better nature. This broken and wrongheaded man’s final arrival at a sort of wisdom and, perhaps fleeting, redemption holds more dramatic power than the bloodiest gunfight. Though there are plenty of those too. [A+]

“The Furies” (1950)

“The Furies” (1950)

The great Anthony Mann (“El Cid”) made a lot of westerns in his day, and next to John Ford and Sergio Leone, he is arguably one of the titans of the genre — albeit lesser-known than those two. Of his acknowledged classics (starring his go-to cowboy James Stewart) “Winchester ’73” “Bend of the River,” “The Far Country,” “The Man from Laramie,” and the aforementioned “The Naked Spur,” none are as acidic and replete with pitch-black-from-the-soul contempt and bitterness as 1950’s aptly titled, “The Furies.” The film starred the inimitable Barbara Stanwyck as a strong-willed firebrand of a woman (when isn’t she?) scorned by her controlling father (Walter Huston in his final role). She disapproves of his empty-headed socialite bride-to-be. He hates her gambling lover. And while the searing domestic melodrama scalds our emotional senses, the two also dispute over land. Their turbulent relationship spirals out of control and out of spite, the father has her lover hanged. The film-noir-charged ugliness curdles into rage and vengeance comes raining down from Stanwyck with a wrath that chills the bones. Martin Scorsese compared it to the dark works of Dostoevsky, and it’s the only Mann-helmed western that Criterion has put out. They should have called this one “Unforgiven.” [A+]

“The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” (1962)

“The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” (1962)

You may have heard of a man named John Ford. He won four Oscars for Best Director in his day and made a lot of westerns. This film is one of his best, and therefore one of the best westerns ever made, period. Told in flashback, ‘Valance’ centers on a state senator (Jimmy Stewart) who is famous for killing a notorious outlaw and returns to a small town for a funeral of an old friend (John Wayne). A journalist starts quizzing him which launches a long recollection of his youth, and out comes the real truth of the deed that reveals the titular outlaw Valance’s death and all of the senator’s subsequent fame and success, to be based on a lie. The film is a gut-punchingly bitter pill in the end, full of regret and loss and unrequited love, so heaven knows how Ford manages to make it so compellingly watchable too. The performances are uniformly excellent, with Stewart playing brilliantly off Wayne and a hard-as-nails Lee Marvin as Valance. Certainly one of the crowning achievement of Ford’s illustrious career, this film along with Ford’s other acknowledged masterpiece “The Searchers” could easily form the backbone of any primer on the dizzying possibilities of the film western. [A+]

“High Noon” (1952)

“High Noon” (1952)

Fred Zinnemann’s “High Noon” ranked #27 on the American Film Institute’s 2007 list of great films, making it the 2nd highest-ranking western after “The Searchers” (John Ford is unfuckable-with) and this reevaluation (the AFI’s list originally hit in 1998) is a wise move. The gracious Gary Cooper stars as Will Kane, the longtime Marshall of a small New Mexican town. He’s about to hang it all up for his new Quaker pacifist bride (a gorgeously luminous Grace Kelly) when he gets word that Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald) — a soulless criminal that Kane brought to justice for murder — has inexplicably been pardoned on some unexplained technicality. Kane can go on to greener pastures with his new wife, but the call of duty is too strong and he returns to rally members of the community to fight off the scum that is heading their way. Famous for being shot in (nearly) real time, which always seems deceptively simple but takes an enormous amount of skill to pull off, perhaps its greatest triumph is that it never becomes merely a formal exercise and actually remains one of the most entertaining of the westerns on this list. And the last scene when Cooper’s character contemptuously tosses his marshall’s tin star at the feet of the cowardly and thankless townspeople? One of the best “go fuck yourselves” kiss-offs in a movie, ever. [A]

“McCabe and Mrs. Miller” (1971)

“McCabe and Mrs. Miller” (1971)

Moody, atmospheric, enigmatic and ultimately brilliant, leave it to Robert Altman to construct one of the shrewdest anti-western westerns of all time. The film follows John McCabe, an ambitious gambler who arrives in a town named Presbyterian Church (after its most prominent building) and naturally, establishes a brothel by purchasing prostitutes from a pimp in a neighboring town. McCabe stumbles into success almost by accident, largely thanks to Constance Miller (Julie Christie), a professional madam who whips McCabe’s makeshift operation into shape. The success of the enterprise catches the eye of of a mining company who want to buy him out as well as the mines surrounding the town, but when he says no, three bounty hunters are set out to kill. Time for a big showdown, right? Not if you’re Robert Altman. The final sequence is jaw dropping because it turns the entire notion of the western hero right on its head. Altman practically mocks the pissing contest between McCabe and the killers by cross cutting their showdown with the battle to contain the fire at the church that has suddenly burned out. McCabe has no problem shooting anyone in the back and as he trudges through the knee-high snowdrifts and blowing wind, the futility of his struggle that is driven mostly by pride is held in stark contrast. Also look out for Keith Carradine, in one of his first film roles, playing the tragic, nameless young gunslinger who gets caught between the two forces fighting for Presbyterian Church. Gorgeously shot by Vilmos Zsigmond like a hazy dream and featuring a lovely, and gloriously anachronistic score by Leonard Cohen, “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” is one of the shining examples of 1970s American filmmaking: an impressionistic, boldly individual and completely genre-defying western that still remains unlike anything before or after it. [A-]

“Open Range” (2003)

“Open Range” (2003)

Post- “Dances With Wolves,” Kevin Costner’s directorial career, well, floundered would be a nice way to put it, with his follow-up efforts (an uncredited directorial stint on “Waterworld,” an all-too-credited stint on “The Postman”) were unable to hit the same epic stride that so impressed the Academy with his debut. And time has not been particularly kind to ‘Dances’ either, revealing it as a rather self-indulgent overlong vanity project that in many ways foreshadowed the frighteningly egotistical bent of his movies to come. So with this unpromising background, “Open Range” is a complete and welcome surprise, and sees a chastened Costner direct himself (as before) but this time with a light touch and a generous desire to showcase the supporting talent. And what talent: Robert Duvall, Annette Bening and Diego Luna are all in fine form, with Michael Gambon as an appropriately dastardly villain. “Open Range” is a classic western full of man’s-gotta-do ethos but leavened with an unusually strong female character and moments of genuine humor. By turns touching, funny and exciting (John Ford would be proud), this overlooked film deserves a lot more attention and praise than it got, and goes some way to help Costner atone for directorial sins past. [A-]

“Winchester ‘73” (1950)

“Winchester ‘73” (1950)

The word ‘seminal’ could be applied to many of the films on this list, especially if like us, you have a full-on stiffy for the western genre. But while it’s a term that is most usually found in reviews of the John Ford/John Wayne oeuvre, there was another great, seminal western partnership during this period: that of director Anthony Mann and star James Stewart. Teaming here for the first time, you can see why they would go on to work together seven more times (four of them westerns). Stewart’s performance is a revelation — keen-edged, desperate, almost deranged at times, and it’s wonderful to see him explode out of the laconic everyman role he often played elsewhere. The plot itself is unusual too, a revenge story built around the titular rifle that digresses at times to follow the rifle’s story, rather than the human protagonists’. But nonetheless, it remains a blistering human drama centering, as so many great westerns do, on a man haunted by his past and trying to embrace his destiny, ultimately discovering the two are irrevocably linked. [A]

“The Misfits” (1961)

“The Misfits” (1961)

Don’t get us wrong, this is a great film that every bit deserves its place on this list. However, with the serious all-star lineup of director John Huston, writer Arthur Miller, stars Marilyn Monroe, Clark Gable, Montgomery Clift, Thelma Ritter and Eli Wallach, and the mythology surrounding it being both Gable’s and Monroe’s last completed film, it’s hard not to have unmatchable expectations going in, with the result that actually watching it can be kind of a letdown. It doesn’t help that the storyline is somewhat disjointed, but the intermittent flashes of true filmmaking genius do make up for it – it’s a fittingly world-weary swansong for Gable, features if not Monroe’s best performance, then certainly her least self-conscious, and the black and white photography (it was at that point supposedly the most expensive B/W movie ever shot) is starkly beautiful in every shot. Something about the confluence of story, star personae and context might make you think this should be the most apocalyptically brilliant western ever made; as it is, it’s just very, very good. Oh, and Monroe’s last line, “How do you find your way back in the dark?” is the most goosebump-raisingly apropos grace note that anyone could possibly hope for. [B+]

Honorable Mentions: Like we said, this piece could have run on forever, and any honorable mentions list will obviously be missing some key films as well. Perhaps the most notable absence here was anything by Leone, who is obviously one of the acknowledged masters of the genre. More than anything, it proved too difficult for us to narrow it down to just one Leone film, but we may run an all spaghetti-western feature in the future to make up for it.

We also felt we were running quite heavy on Peckinpah, and, as great as it is, weren’t sure if we had anything new to say about “The Wild Bunch,” but if you’ve never caught it, it’s certainly a must see. Otherwise, Monte Hellman’s “The Shooting,” “How the West Was Won” and “The Man From Laramie” were all near-misses, and films we may return to down the line.

While there may not be as many oaters around as there used to be, there’ve been a few classics in recent memory — principally John Hillcoat’s “The Proposition” and Andrew Dominik’s “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford.” However, we’ve covered both at length in the past, and felt that there were better uses for the space. The Korean western “The Good, the Bad, the Weird” is also a heap of fun, even if it is kind of a mess. As ever, let us know your favorites in the comments below.

— Jessica Kiang, Rodrigo Perez, Oli Lyttelton, Gabe Toro, Chris Bell, Kevin Jagernauth