In case you needed a primer on what a lobbyist is, “Casino Jack” has got you covered. Based on the rise and fall of disgraced Washington man-about-town Jack Abramoff, the comedy-drama explains with great detail and full color exactly what a lobbyist does, what sort of influence they wield and their reputation amongst the Beltway set. Director George Hickenlooper’s outlook is, of course, that these people are cockroaches. Whether he’s correct or not is irrelevant to the content of the film itself. But between you and me, yes, he is.

Kevin Spacey stars as the abrasive, fast-talking Abramoff as he plans to expand a mini-empire beyond moving and shaking the very roots of democracy. We first meet him as he’s fast-talking Native Americans into building casinos over games of golf, pitting tribes against each other as they struggle for financial supremacy over certain extinction. Abramoff, of course, is entirely pragmatic, focusing not on the abuse being levied on a damaged subculture, but on the good he will do once he secures the funds from this venture.

Of course, dirty money begets dirty money, and it’s not long before his abuses extend to the sea as he tries to branch out into illegal offshore betting. A vain braggart who wallpapers offices with posters of “Red Scorpion,” the middling Dolph Lundgren movie he produced, Spacey’s Abramoff runs like a constant bad-idea machine, his questionable activities and altruistic goals (building a school, kosher D.C. restaurants) both shrines to his ego. He is enabled by worker bee Mike Scanlon (Barry Pepper), an over-caffeinated (and then some) assistant with a belligerent disposition supplanting the charisma. A scene where Scanlon, sent in place of Abramoff, ruins a negotiation with an Abramoff-like stab at humor stings, for there are many levels of inferiority that are at play, exhibiting multiple power structures within a simple, botched Travis Bickle impersonation.

The Abramoff of “Casino Jack” is nothing if not a repugnant brat. As played by Spacey, the film chooses to showcase his naturally charming side, with Abramoff envisioned as a motor mouth who peppers conversations with extended impersonations or movie references. Spacey never seems like a natural fit for the character, bellowing that he “works out every day” when the slightly-puffy actor looks like he might take two or three jogs a week. He’s our hero because it’s Washington — every other character is a rube or enabler.

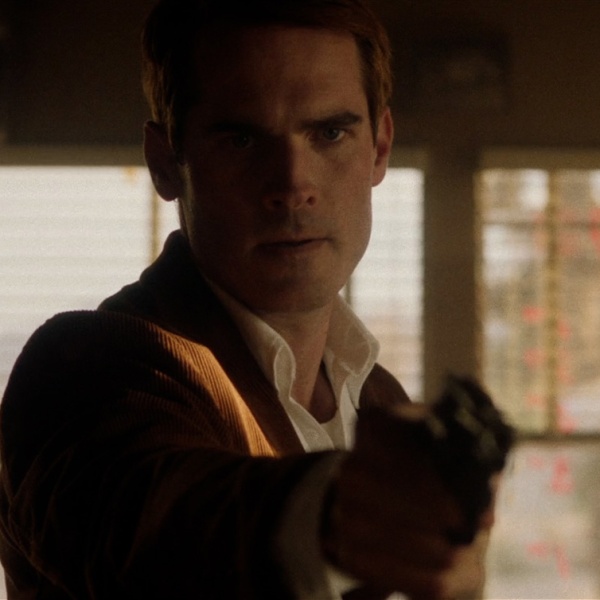

That includes Adam Kidan, the mattress millionaire who Abramoff enlists as a purveyor of capital for his high seas adventure. As played by Jon Lovitz, Kidan is a sad-sack alcoholic, his droopy eyes suggesting a lifetime of knowing he’s been a fool, whether it be in service to business associates, accountants or ex-wives. Broke and desperate, he jumps at Abramoff’s offer to oversee the gambling operation, because that’s exactly what you do when you’re broke, drunk and lonely. The promise of piles of money and fast women light up his eyes before he’s forced to contend with Abramoff’s dirty laundry, in the form of the organized crime-types Abramoff had to muscle out of the business. Soon, Kidan, who comically knows not what to do with the topless women crowding his couch, is a target, leading to the clandestine involvement of the type of shady men with guns you’d expect to be involved with mattress millionaires.

Director George Hickenlooper sadly passed away earlier this year, but he’s left us with a funny, acidic take on Washington insider politics. But with what purpose? Abramoff’s scheming seems like Ralph Kramden’s various get-rich-quick ideas, in that the film has no weight until the very end, and even then, not so much. Much of that comes from the lackluster framework — “Casino Jack” is not a particularly well-shot or tightly-edited film, feeling often like its own outtake. Hickenlooper was a fan of the dolly-shot closeup that renders the camera’s focus into a subject larger-than-life, an attitude that says a significant amount towards the treatment of our doomed protagonists, in that they seem altogether bulletproof (with the exception of death-wish Scanlon, who never found a way he couldn’t sabotage himself).

Knowing Abramoff, we know the ending, but as it arrives in the film it tries to play as both heroic and tragic, working as neither. Abramoff, and the film, wants you to believe that he was merely taking the cookie out of a cookie jar that was already stolen, and that his crimes are far less severe than the fatcats in Washington with more leisure capital to abuse. The tragedy is that the American system is corrupt, but that only works if you like Abramoff, a sneering, dishonest, corrupt businessman who at least in the movie’s forgiving eyes has delusions of do-gooderism. And the heroism stems to Abramoff’s Dolph Lundgren-fueled promise to return to Washington years later and expose the enablers in Capitol Hill that turned their heads while he committed misdeeds. Which, as who knows anything about Washington knows, is total bullshit. [C+]