In “The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage Of The Dawn Treader,” we return to the Pevensie siblings and their adventures across the mystic lands. However, because the last film, “Prince Caspian,” didn’t exactly set the world on fire, we get everything at a discount: hence, instead of four Pevensies, we get two. Sea serpents don’t just pay for themselves. What a world that would be.

It’s always something magical but eerily unexplained in the ‘Narnia’ films that gets the kids to the fantastical realm. In the first one, it was a closet, and the second a whizzing train, but here, it’s a painting. The children hang it up on the wall of their dwellings, another drab British abode populated by their cousin and his father (the latter unseen, because the production could only afford so many faces). The cousin of note is played by Will Poult, the young bully from “Son Of Rambow,” who here plays Eustace, a nitpicking worrywort who might as well wear a shirt that screams, “ATHEIST.” He’s a pacifist who doesn’t believe in fantasy and fairy tales, and spends his time reading, as he puts it, “books with FACTS.” Little charmer.

Little Edmund (the DC Comics-sounding Skandar Keynes) is now 16, but determined to prove himself with an eye towards enlisting in the army. The assumption is that, when pressed, he will tell people of his considerable war experience battling fairies and dwarfs in Narnia, but nosy sister Lucy (Georgie Henley) puts the kibosh on this idea. She, too, is battling her own inadequacies: now a full-grown teenager, she yearns to have the beauty of her older sister, who previously romanced Teen Beat dreamboat Prince Caspian (Ben Barnes). While a pretty young girl in her own right, reality dictates this is one of those problems that just can’t be resolved.

But why bother with reality when the Pevensies and their cousin are swept away into magic-land via magical painting? In an instant, they are floating at sea, the watercolors engulfing their bedroom in a wave of Jesus liquid. Conveniently in the territory of real-world-painting-nexuses, the now-King Caspian and his crew are sailing nearby, and they rescue the children and bring them aboard the ship. Long story short, is there an evil that needs to be vanquished? Do they need children to bear weapons to get out of this mess? Is there a minotaur? Does Simon Pegg voice a chivalrous, sword-fighting CGI mouse? If you’ve seen a ‘Narnia’ film, none of this will be a surprise. If you’ve seen ‘Harry Potter,’ none of this will be a surprise. Hell, if you’ve seen “The Seeker: The Dark Is Rising” or “Eragon,” your attention span will handle it with one eye open.

Most of the action is seabound (read: on a tacky set) with a couple of adventures off the shore. One of them involves the children arriving at a small village where they are kidnapped and sold into slavery by swarthy men in robes and headdress. Lest you feel that Disney wouldn’t release a scene where one of the Pevensies is auctioned off to an obvious rapist, calm your concerns: Fox is handling the distribution this time. Whole new ballgame.

The assumed strength of the ‘Narnia’ movies, the notion that there is no limit to the magic present, is also a weakness. Every territory lends itself to its own spells and intrigue, meaning that there appear to be no rules to the action onscreen whatsoever. Well, unless you consider Aslan the gatekeeper. The furry lion overlord who sounds a lot like Oskar Schindler keeps showing up in their time of need. And by time of need, we mean when Lucy is looking in the mirror praying for beauty tips. Or when Eustace needs to be changed into a dragon to become a “believer.” Or when he wants to show off Heaven. Things like that.

As a result, Narnia keeps throwing things at these kids. You’re not supposed to raise a stink when you realize that a group of pathetic, invisible, one-legged dwarfs are at the bottom of the Narnia caste system, which seems messed up when they lead Lucy to a magical book of spells they can‘t read. Blame the weak education system for one-legged dwarfs in this Narnian ghetto. These spells sit in this book during a climactic battle with sea serpents (“Sea serpents?” one character wonders incredulously while standing next to a giant, sassy Minotaur) because they would alter too much about the characters and cause them to, apparently, believe in themselves just that much less. It’s fear of change and victory for the status quo that fuels the ‘Narnia’ imagination machine — the movies seem to be one real step removed from a genuine horror film in their “return of the repressed” story beats.

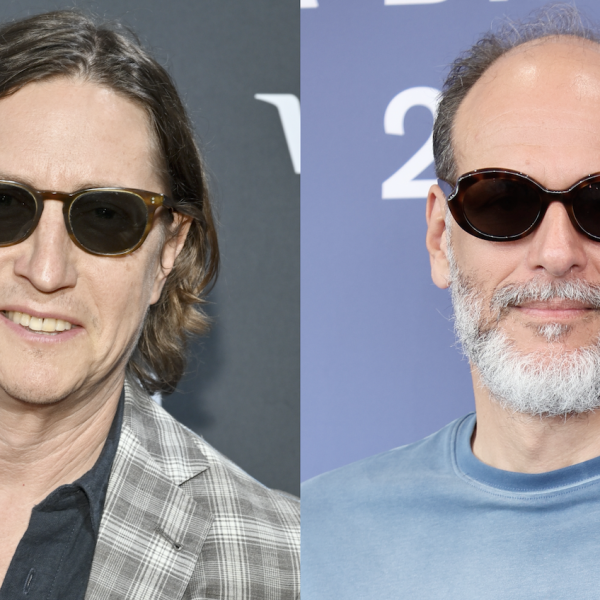

Three movies into the ‘Narnia’ series, this style of filmmaking has simply become cynical and perfunctory. Part of this comes from the staid direction of Michael Apted, a skilled storyteller and capable journeyman who seems lost with the intricate CGI-battles. The first two films benefited from the competent technical skill of animation vet Andrew Adamson. Apted, by comparison, has essayed a number of smaller character dramas, but with no actual characters to mind, he’s lost aping the imaginatively bankrupt visual vocabulary of every single fantasy movie that’s arrived before and ignoring the limitations of the visual effects in easily the worst the series has seen yet. More predictably, the 3D, from a post-conversion process, is flat and unconvincing, muting the film’s sole visual flourish, the vibrancy of the bright blue ocean setting. This is thrown into sharp focus with the film’s failure of visual geography — Apted fails to hide the fact that the sets are much smaller this time around, shooting them as if they were expansive dioramas and not a couple of square feet in a studio somewhere.

Did we mention the plot, involving some MacGuffin-fueled chase for seven bearded Gandalfs (called “Lords,“ but clearly just a squad of Ian McKellen impersonators), hinges on the Earth being flat? Not only is Narnia’s sorta-Earth one-sided, but at the end of the world, instead of falling off, you arrive at an actual Heaven? It’s one of many instances ‘Narnia’ uses to flatter ignorance, though the simplistic Christian overtones of these films seem more of a sad portrayal of the inane sturm und drang of studio fantasy films than any specific backwards celebration of faith. Like the characters approaching the fringes of the Earth, the good bet is that this series has reached the end of the road. We couldn’t be happier. [D-]