Despite over-saturation, a refusal/inability to use the film medium to its full potential, and the generally low-aiming nature of the mumbly micro-indie, it seems the genre is here to stay.

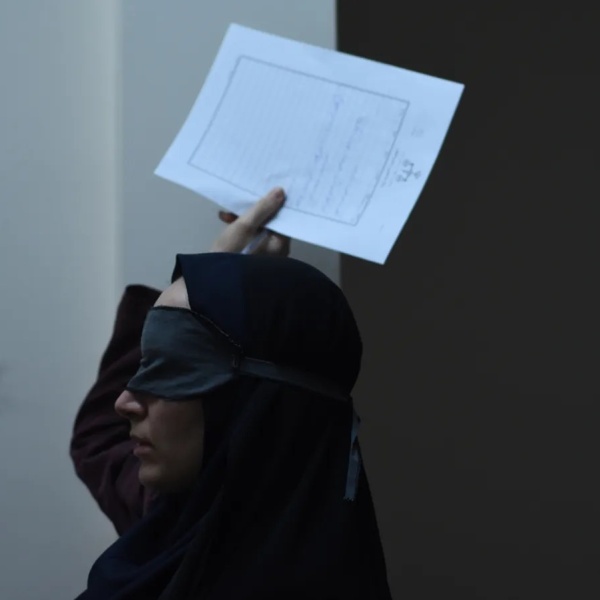

Entering the ring is the SXSW-approved “You Won’t Miss Me,” directed by New York-based filmmaker Ry Russo Young. Stella Schnabel, daughter of Julian (“The Diving Bell and the Butterfly“), plays her first role not under her father’s eye as the troubled protagonist Shelly. The movie commences with a meeting with her psychiatrist, and it slowly trickles out that she is being released from a mental facility despite her reluctance to return to the outside world. Remaining interview segments are sprinkled throughout the film, with the narrative mainly focusing on her attempt at reconnecting with friends, work, and life in general. She tries to ease back in, catching up with her friends at social outings and attempting to kickstart her acting career by attending various auditions. There are budding romances and one-night stands, but relationship opportunities are nil. Eventually her relationship problems and negative personality begin to eat away at her new start, sapping any desire she had to have a productive existence.

Similar to recent movies like “The Girlfriend Experience,” ‘YWMM’ treats the narrative as an erratic collection of scenes, much like how the mind would process things as they were currently happening, interspersing them with memories that may or may not be related. In this sense it’s one of the most ambitiously structured pieces in its clique and the format does it a lot of good: while we see a troubled individual unable to cope with life and lashing out at those around her (read: a bitch), Young craftily drops in other moments which illustrate a much more complex character than we would have seen had the narrative been more linear. The inclusion also serves to do more than add dimensions to the character, as these montages prevent the film from being too cold and one-note.

Too bad, then, that everything else feels either lazy, uninspired, or insubstantial. Admittedly, it has a lot to do with the acting: non-actor unrestricted improv isn’t very affecting, despite what a large group of filmmakers would lead you to believe. The goal to create a situation that’s as real as possible is completely understandable, but throwing a few people in front of a camera and giving them a loose agenda is an overplayed card that isn’t just boring, it’s now becoming grating. What works for rehearsal doesn’t jive in a film, and most of these scenes feel like the first take of Schnabel trying to pull something out of these non-actors, with some close-up coverage thrown in to cover up mistakes.

People act a certain way in front of a camera, they exemplify certain traits (usually by trying to be funny or more confrontational) because they know there is an audience. The result is less natural, thus defeating the original intent. There’s also loads and loads of dialogue as these antsy people struggle to get somewhere in a particular scene. So much, in fact, that they become reliant on discourse and do very little visually. It’s a shame, because all the subtleties and nuances that the film medium is capable of are completely lost in this wave of films, which opt for tightly-framed character-driven plots that would almost always be better served as stage plays. Aside from not being very visual, watching these scenes is downright boring. One particular poor example involves the main character and a friend hanging out with a band, with Shelly interested in one of the members. He soon passes out and she becomes jealous of her flirtatious acquaintance, which leads to a vicious post-party argument between the two. It works only until Schnabel’s character basically goes from drunken rant to ham-fisted monologue, bleeding the situation dry and eschewing any sense of realism. It ultimately feels cheap.

Young does manage to hit the nail on the head with at least one scene and does so rather eloquently. Shelly attends an audition, the final one in the film, held by director Aaron Katz (“Quiet City“) and featuring an appearance by both Joe Swanberg (“Alexander the Last“) and Greta Gerwig (“Greenberg,” thus fulfilling quota). Katz organizes a less-than-traditional tryout, having two actors swing their arms around and improv a dialogue. What sounds annoyingly quirky is actually interesting to watch and almost feels like a jab at the movement, especially given all of the cameos in this one scene. Young quietly observes the tug of war between Gerwig and Schnabel, with the former clearly getting the better of her. Schnabel’s character knows she flubbed the audition, and with ego dented she decides to dig into Katz’s “pretentiousness.” It’s painful and very genuine, and while there is cutting dialogue it is brief and, for the first time, the director seems to pay attention to Schnabel’s body as opposed to just her words. The camera lingers a bit on her striking figure, one that doesn’t need to say anything to seem damaged; if only Young had harnessed this throughout the film, we’d have something truly powerful.

With almost no one to turn to (her conversations with her Mother just involve voicemails) and becoming increasingly lost, Shelly and her best male friend share a smooch before he ultimately gives her the “close friend” let down, and the movie ends with a giggle by Shelly in the final sequence with her doctor. Overly pessimistic, sure, but really the most bothersome thing is that, in the end, it’s rather empty. There are no questions being raised, no real critiques of anything, no conversation with the audience, and we certainly don’t care about any of these characters. It seems the only point was to create a “realistic character,” and if that is true than it’s simply not enough. Its refusal to delve into the complexities of human behavior – though making a film that is essentially a character study – is downright draining. Whereas a character-driven piece should be striking and moody, this seems to simply detail a breakdown with no insight into it.

“You Won’t Miss Me” does a few interesting things, both traditional and experimental, but suffers from its clique’s worst attributes, and fails to use its strengths to overcome those shortcomings. [C-]