On May 31st this year, Clinton “Clint” Eastwood reached 80 years of age, and he’s been acting for 56 of them. Remarkably, since TV show “Rawhide” made him a star in 1958, he’s been at the top for almost all that time, having had major box office hits in every decade since the ’60s: most recently, “Gran Torino,” which surprised most pundits by taking in over $250 million worldwide. There’s never quite been an acting career like it, and a retrospective on Clint Eastwood: movie star, would show the breadth and depth of his career.

But in recent years, Eastwood’s been better known as a director, and has major movie stars like Matt Damon, Leonardo DiCaprio and Angelina Jolie falling over themselves to be involved in his projects. He’s able to pick and choose from the very best writers and collaborators (Oscar winners Peter Morgan and Dustin Lance Black wrote his two most recent projects), and film festivals, most notably Cannes, where he’s something of a favorite, fight for the chance to premiere his latest films. With his latest directorial effort, “Hereafter” expanding to a wider audience today, it seemed like as good a time as any to look at Eastwood’s work behind the camera.

We have to admit, we’ve had our reservations in the past about Eastwood as a helmer: his recent output seems to have suffered from the no fuss, let’s-keep-it-to-one-take-so-we-can-be-on-the-links-by-five approach that actors in his films have reported (normally in a positive way, it should be said). But in putting this piece together, we’ve found a renewed appreciation. For an actor who fits into certain stereotypes fairly easily, his directorial work is varied and unpredictable, and even when the films don’t work, they’re pretty fascinating.

And when they do work, and there’s several stone-cold classics on this list, there are few working in American cinema who can match him. We haven’t included everything, particularly in Eastwood’s fallow period in the 1980s (mainly because no-one really wants to read 300 words on “Firefox”), but the significant films are all here after the jump, and it’s enough to make even those of us who haven’t been on the Eastwood train of late eagerly anticipate next year’s “Hoover.” And for everything that’ll follow that too…

“Play Misty For Me” (1971)

“Play Misty For Me” (1971)

The premise for Eastwood’s directorial debut might seem absurdly comical today but hey, it was the ‘70s so cut the guy some slack. The film follows Eastwood, playing a radio DJ who meets a woman who, at first, seems to be a playfully obsessed female fan. She constantly calls into his radio show requesting Errol Garner’s “Misty” and soon Eastwood is curious enough to meet her. They have a one night stand and Eastwood thinks that’s it for her, but as these sorts of stories go, she won’t let him get away that easy. The film has a breezy sort of charm, a few genuine thrills that make it an easy watch on a late night. But the film is also anonymously directed, completely forgettable, and kind of dumb. In many respects it’s a “First Film” through and through, with all the imperfections that come with the territory. One to get under your belt and get those muscles moving and to that end, it delivers what you might expect. If anything, the film served as an announcement by Eastwood to his fans, that “Hey, I like jazz music, okay?” and well, mission accomplished. [C]

“High Plains Drifter” (1973)

“High Plains Drifter” (1973)

This might be Eastwood’s most overlooked Western and also his most interesting, especially when it’s read as a horror Western, instead of just a straight-up gunslinger tale. Eastwood plays The Stranger who defends a small mining town against a bunch of bloodthirsty villains, which is typical Western fare. But the movie has a surprisingly raw edge, especially for populist entertainment in 1973, with strong violence and sexuality. But the genius of “High Plains Drifter” lies in its supernatural overtones, replete with numerous biblical references — the town Eastwood defends is initially called Lago but is re-titled, in a swath of red paint, as Hell — and there’s a nasty dwarf, played memorably by character actor Billy Curtis, named, biblically, Mordecai. The movie is, visually and thematically, indebted to Sergio Leone and Don Siegel (whose names appear on tombstones in a graveyard sequence in the film), with a much stranger tone that’s more akin to modern day revenge epics (Tarantino borrowed heavily for the second half of “Kill Bill” and Edgar Wright is an admitted fan) and ghost stories, than the spaghetti Westerns Eastwood was so well known for. If you’ve never seen it, you owe it to yourself to check this one out. This is one of the highlights of his entire career. [A-]

“The Eiger Sanction” (1975)

“The Eiger Sanction” (1975)

As was revealed recently, Eastwood was offered the role of James Bond by the Broccolis after Sean Connery left the franchise. While it’s almost impossible to imagine Eastwood in that iconic role, “The Eiger Sanction” perhaps offers the best guide as to what he would have been like. And quite frankly, it makes us glad that bit of casting never came to pass. As mild-mannered art professor Dr. Jonathan Hemlock, who’s actually a retired CIA assassin, called out of retirement for the proverbial one last job, Eastwood is woefully miscast, but his performance is genius compared to the film around him. Thayer David is reasonably good value as Hemlock’s albino ex-Nazi boss, but even that character description gives a good sense of how nonsensical and badly told the plot is. Furthermore, there’s a nasty streak of unreconstructed homophobia running through the film that would send Vince Vaughn running to the nearest GLAAD fundraiser, and there’s a sadistically violent streak that would recur in many of the “Dirty Harry” sequels. Probably the only bright spots are the well-staged mountaineering action sequences, but even those were obtained at a high cost: there were a number of accidents during filming, including the death of body double David Knowles. Cameraman Frank Stanley, who was badly injured in another fall, criticized Eastwood as “a very impatient man who doesn’t really plan his pictures or do any homework. He figures he can go right in and sail through these things.” It’s almost extraordinary to think that Eastwood could go from this black mark to one of the very best films of his career, but that’s typical of the man… [D]

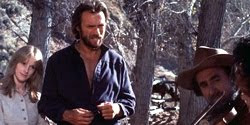

“The Outlaw Josey Wales” (1976)

“The Outlaw Josey Wales” (1976)

The Western made Clint Eastwood, and Eastwood made the Western– time and time again. The term “revisionist Western” is practically synonymous with Eastwood, and “The Outlaw Josey Wales” happens to be his anti-war Western. Like many Westerns, Eastwood uses the safe space of the past to express the trauma and anger felt in the post-Vietnam era. That’s not to say that this is some peace loving, pacifist tale. With Eastwood at the helm? No sir. His Josey Wales is the epitome of the cool, skilled gunfighter character, an outlaw because of his violent vendetta against the corrupt Union Army “Red-Legs” who brutally murdered his wife and child. Wales joins a Confederate guerrilla group, spills a lot of Union blood, and earns himself a bounty on his head in the process. Against all odds, he ends up accumulating a diverse band of strangers to serve as his de-facto family, including an older Cherokee (Chief Dan George), a young Navajo woman, a gun-toting granny, and an innocent-yet-sexy hippie chick. The action-packed Western is vintage Eastwood, but it’s not vintage Western. Eastwood uses the language and symbolism of the Western to turn the genre on its head and tell his own moral story. He presents character archetypes well-known to the audience versed in the traditional Western, and then plays them out in unexpected ways. Ultimately, the audience comes away with a sense of the moral corruption of war, the love of a family (traditional or not), and the power of the individual. Oh, and the truly awesome motto, “dyin’ ain’t much of a livin’, boy.” [B+]

“The Gauntlet” (1977)

“The Gauntlet” (1977)

A movie that has its fans (it was recently reissued on Blu-ray, so somebody’s got to still dig it), and is fairly entertaining in a down-and-dirty, genre-picture-made-in-1977 type of way, but it’s in no way as memorable as its macho-overload poster designed by the one and only (and dearly departed) Frank Frazetta. That image, an oversized depiction of the movie’s extended finale, in which an alcoholic Ben Shockley (Clint Eastwood) escorts a loudmouth prostitute (Sondra Locke), who also happens to be a witness in a huge corruption case, through the titular gauntlet of corrupt cops. The poster betrays an atmosphere of post-apocalyptic devastation, which suggests a much more interesting and vibrant movie than Eastwood actually delivers. While the plot moves quickly along and Eastwood stages the action sequences with the appropriate amount of flair, “The Gauntlet” is hamstrung by Eastwood’s decision to cast Locke (who Eastwood was dating at the time) in the prostitute role. She was supposed to be initially grating but ultimately likeable, but with Locke in the role she’s just out-and-out irritating. Ultimately “The Gauntlet” is fun while you watch it, but not all that memorable. And it can’t hold a candle to that poster. [B-]

“Pale Rider” (1985)

“Pale Rider” (1985)

Clint Eastwood’s work both in front of and behind the camera throughout the 1980s has never earned quite the critical acclaim of his ’70s output, nor his “renaissance” period in the early ’90s. But the ’80s represent an important turning point for Eastwood, and 1985’s “Pale Rider” aligns itself with 1980’s “Bronco Billy” as a subtly political film; if the latter took the nation’s temperature after its defeat in Vietnam, ‘Rider’ was the movie for a moment that saw Ronald Reagan begin his second term as president. The film’s plot plays like a capitalistic take on Akira Kurosawa’s “Seven Samurai“: A small settlement of gold miners in the California foothills call upon a mysterious, unnamed stranger to protect them from the tyranny of corrupt authorities. Eastwood plays the Unnamed Stranger, a preacher/gunslinger and a symbol of honest American values. His presence offers not only physical protection but spiritual motivation, as his character hones the same message of courage and accountability “Bronco Billy” cannily directed at a nation fresh off Watergate. This underlying complexity helps distract from the film’s sometimes sloppy scripting (corniness plagues so much of Eastwood’s work, this being no exception). Further, Eastwood’s gift for crafting evocative imagery—including a unique take on “The Searchers‘” iconic doorway-framing shot which uses a darkened interior and lit exterior as a potent visual metaphor for his character’s shrouded past and chance at eventual redemption—makes this one of his most striking and sturdy Westerns. [B+]

“Bird” (1988)

“Bird” (1988)

Considering his reputation as a big-screen tough man, it’s somewhat remarkable that one of the more successful and sensitive musical biopics, a genre full of disastrous attempts to overexplain legends, came from Clint Eastwood. But the noted jazz enthusiast (his son Kyle is a jazz musician, and Eastwood Sr. composed jazz-inflected scores for several of his films of the ’00s, as well as for James C. Strouse‘s “Grace Is Gone“) hit a real passion project with Charlie Parker biopic “Bird” and his love for the music and the man shines through. Forest Whitaker, in one of his earliest high-profile roles, is sensationally good, picking up a Best Actor award at Cannes, with the ever-underrated Diane Venora easily his match as his last wife Chan. It doesn’t shy away from the darker aspects of Parker’s life either (he was addicted to heroin for basically all his adult life), but still manages to keep on the right side of cliche. However, the film falls down in its loose structuring, which is appropriately jazz-like, but rather works against the picture, and it’s hard to walk away without feeling that 20 minutes could have been happily shaved from the film. What shines through, however, is Eastwood’s love of the music, which is outstanding — Eastwood and music coordinator Lennie Niehaus isolated Parker tracks from original recordings, then mixed them with contemporary musicians, paying tribute to the man while keeping the music fresh. [B+]

“White Hunter Black Heart” (1990)

“White Hunter Black Heart” (1990)

Considering he’s now spent over 50 years on film sets, you’d think that Eastwood would have made movie-making the subject of a film earlier than 1990’s “White Hunter Black Heart.” But anyone looking at this film for an insight into Eastwood’s working methods — his portrayal of obsessive director John Wilson (a very, very thinly veiled version of John Huston during the making of “The African Queen“) doesn’t strike one as anything close to Eastwood as director, even if you substitute “trying to shoot an elephant” for “playing a round of golf.” It is an undeniably enjoyable film — somewhat looser and funnier than much of Eastwood’s work — and its examination of machismo shows the director to once more be a more contemplative figure than his onscreen figure sometimes suggests. But Eastwood the actor seems out of his depth, seeming preoccupied with impersonating Huston, and coming across as somewhat mannered as a result. Jeff Fahey is fairly strong as his foil, and George Dzunda is entertaining as the Sam Spiegel surrogate, but for the most part this is a one man show where the one man proves to be a disappointment. [C+]

“Unforgiven” (1992)

“Unforgiven” (1992)

Considering it’s now close to twenty years since he tackled the genre, one would think that Eastwood would have considered returning to the Western by now — after all, Kevin Costner doesn’t seem to be able to go five years without taking another crack at the genre. But then, if we’d made “Unforgiven,” we’re not sure we’d have anything left to say either. Almost inarguably the crowning achievement of Eastwood’s career to date, the revisionist Western had been floating around the industry for years, with the director eventually buying up the rights, but deciding to wait until he was old enough to pull off the lead role. And we’re glad he did — no-one else would have brought the baggage (and we really do mean this in a good way) that Eastwood does here; the history of his career weighs heavy on the shoulders of Bill Munny. The key line here is “It’s a hell of a thing, killing a man. Take away all he’s got and all he’s ever gonna have,” and Eastwood plays Munny as though the weight of every life he took on screen, from The Man With No Name to Dirty Harry, is catching up with him. He’s ably assisted by a killer supporting cast, particularly Gene Hackman, Morgan Freeman and Richard Harris, and a magnificent script from David Webb Peoples (“Blade Runner“). Eastwood’s never felt so confident behind the camera, either, and his take on the genre that he’d already made a hell of a stamp on has influenced everything since, from HBO’s “Deadwood” to the Coen’s upcoming “True Grit.” He’s not topped it since, but we’ll put up with “Changeling” or “Hereafter” if we think that Eastwood will ever get close to this again. [A+]

“A Perfect World” (1993)

“A Perfect World” (1993)

Coming off probably the greatest achievement of his acting and directing career (and an acting-only role in the sizable commercial hit “In The Line of Fire” in between), nobody expected Eastwood to match “Unforgiven” next time out at bat. What was truly surprising was how close the director came with “A Perfect World.” Teaming for the first and only time with Kevin Costner (at that time, and it’s hard to conceive now, easily the biggest movie star in the world), Eastwood originally intended to only direct, but was persuaded by Costner to take on the supporting role of Texas Ranger Red Garnett, who pursues escaped convict Butch Haynes (Costner) after he takes an eight-year-old Jehovah’s Witness boy hostage. Eastwood’s solid, but it’s the performances he draws from both Costner, who’s rarely been better, proving enormously sympathetic without ever letting us forget the cold-blooded killer that he is, and child actor TJ Lowther, that make the film. Maybe, at close to two-and-a-half hours it’s a touch too long, but as Eastwood’s most lyrical film (you wouldn’t be crazy to call it Malick-esque in places), you’d be reluctant to cut a frame. And the deep, desperate melancholy, and unexpected humor, mean that, while it may never quite get the due it’s owed, it’ll remain the great hidden gem of Eastwood’s directorial career. [A+]

“The Bridges Of Madison County” (1995)

“The Bridges Of Madison County” (1995)

Surely the chick-flickiest entry in Eastwood’s directorial canon, ‘Madison County’ is essentially a “Brief Encounter” retread: a story of decent, honorable people struggling with dishonorable urges but ultimately choosing the not-terribly-fulfilling rewards of Doing the Right Thing over Following Your Passion. Based on the literary phenomenon that was the novel of the same name (though ‘novel’ is a misleading word, as the average National Enquirer probably takes longer to read), the film, aside from some wooden supporting performances (particularly from the grown up children who, in painfully didactic manner, Learn A Little Something About Life from reading their mother’s journals) has actually weathered the passage of time rather well, mainly because at its heart is the utterly convincing relationship between Eastwood’s photojournalist and Meryl Streep’s Italian-born Iowa housewife. Really the film is a two-hander, with everything outside of the two of them talking themselves into and out of their love affair feeling, well, totally extraneous. Streep, especially, is sublime — in her hands small nuances, like covering her mouth when she laughs, suggest whole interior worlds of unrealized dreams and thwarted desires. Of course, the star cross’d lovers theme has been done to death, and no particularly new ground is covered here, but this is a film that plays to Eastwood’s strengths: he may have become famous as the laconic embodiment of the tough-guy-who-takes-no-prisoners, but as a director he is far more preoccupied and adept with talky, interpersonal relationships, drawn with an keen, humanist eye. And, also to his credit as a director and a co-star, he recognizes when he’s on to a good thing in someone else’s performance and graciously stays the hell out of the way. [B]

“Absolute Power” (1997)

“Absolute Power” (1997)

Based on one of the most successful airport novels of the post-Grisham 1990s, “Absolute Power” has a truly ludicrous logline: a successful jewel thief (Clint Eastwood) accidentally witnesses a drunken tussle between a powerful man and his mistress, which ends in his bodyguards shooting and killing the woman. The powerful man being, of course, the President of the United States (Gene Hackman). Despite its best intentions, the film never quite overcomes the ridiculousness of its central plot. The cast, save a somewhat-on-autopilot Eastwood, are strong, with hall-of-fame character actors like Laura Linney, Ed Harris, Scott Glenn, Judy Davis, Melora Hardin, Richard Jenkins and even E.G. Marshall (in his final screen role) turning up, and there are a handful of decent set pieces. But even the great William Goldman, who wrote in his must-read memoir “Which Lie Did I Tell” that the script was the hardest job of his career, can’t make the plot work, and it doesn’t help that Eastwood’s typically languid pacing doesn’t suit this kind of “24“-style potboiler. You’ll have worse times if it turns up past midnight on HBO, and it’s still better than either “True Crime” or “Blood Work” in the “mediocre Eastwood crime pic” trilogy, but a very, very minor effort all the same. [C]

“Midnight In The Garden Of Good and Evil” (1997)

“Midnight In The Garden Of Good and Evil” (1997)

Eastwood took on his third best-seller in a row with “Midnight In The Garden Of Good and Evil,” but, true to form, it saw a major left turn for the filmmaker, abandoning the housewives’ romance and the airport thriller for a full-on slice of Southern Gothic. Based on John Berendt‘s true crime book, which followed the four (!) trials of Savannah antiques dealer Jim Williams for the murder of his rent-boy lover, the adaptation (which saw Eastwood reunited with “A Perfect World” writer John Lee Hancock, a full decade before the latter took Sandra Bullock to an Oscar with “The Blind Side“) condenses the trial down to one, and adds a reporter character, played by John Cusack, who’s our eyes into the bizarre Georgian world of the book. Kevin Spacey, as Wiliams, gives one of his last great performances before his post-Oscar slump, and Jude Law makes a strong impression in a relatively early role. But Cusack’s given next-to-nothing to do, and Eastwood’s daughter Alison, as Cusack’s love interest, is a piece of nepotistic miscasting that Francis Ford Coppola would be proud of. Most importantly, Eastwood never penetrates the surface of Savannah, Georgia: even the real-life residents, like drag queen Lady Chablis, playing herself, never come across as anything other than window dressing. A missed opportunity, to be sure, but not an uninteresting one. [C+]

“Space Cowboys” (2000)

“Space Cowboys” (2000)

“Old coots in space” seems like a logline cooked up by a bored executive on a lazy afternoon. But, in Eastwood’s more-than-capable hands, it turns into something that is actually quite entertaining and bristles with moments of pure popcorn excitement despite its marathon-like 130-minute running time. The old coots (played by Eastwood, Donald Sutherland, James Garner, and Tommy Lee Jones – with an assist by James Cromwell) have to go into space to repair an ailing satellite left over from the space race that is so out-of-date, they’re the only ones with the knowledge to fix it. So the concept is somewhat sound. But the real fun of the film is watching the fogies get back into NASA-approved shape, with each actor comically exaggerating their old timer-ness to an almost cartoonish degree. (But hey, that’s okay.) Once the mission gets underway, Eastwood surprisingly handles the stronger action beats (which border on sci-fi – a genre he’s never had much use for) with flair, thanks in large part to the heroic visual effects by Industrial Light & Magic. Sadly, as the film reaches its conclusion, “fun” is swapped out for “achy melodrama” and the energy sustained for so long throughout slips away. It’s a movie that, if it’s on cable, you might stay and linger on while flipping through channels, but you wouldn’t ever want to watch it all the way through again. [B-]

“Blood Work” (2002)

“Blood Work” (2002)

This, for this writer at least, was the first indication that maybe Eastwood shouldn’t direct every good script that slides across his desk. “Blood Work” was adapted from a crackerjack Michael Connelly novel by the great Brian Helgeland (who would become a frequent Eastwood collaborator) and is centered around a hum-dinger of a crime movie conceit. Eastwood plays a FBI Agent whose life is saved by a heart transplant. The person whose heart Eastwood received was murdered, and the murder victim’s sister (played by solid character actress Wanda de Jesus) implores Eastwood to solve the crime. It’s a thriller with all of these built-in psychological and spiritual questions, plus a really cool plot. What could go wrong? Well, Eastwood’s sluggish direction, for one; plus the fact that Eastwood is just not a great director of suspense set pieces (some may disagree, but the thriller aspects of “Mystic River” were probably its soggiest; ditto “Absolute Power”). Taking your time and building things appropriately makes sense, but when you could feel that the audience was a few steps ahead of the director (and the characters on screen), something was wrong. It was one of the first times that you felt Eastwood’s age as a director, and it felt OLD. [C+]

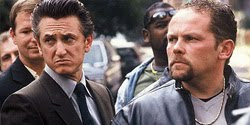

“Mystic River” (2003)

“Mystic River” (2003)

For film auds coming of age in the shadow of Dirty Harry, “Mystic River” marked the resurgence of Clint Eastwood, Oscar-winning director of note. For most everyone else, this was a strong-willed reminder that Eastwood continues to be a considerable talent behind the camera. Based on the novel by Dennis Lehane (who’s built an empire of evoking gritty morality tales of working-class Bostonians caught between forever blurring lines of right and wrong) and adapted quite capably by screenwriter Brian Helgeland, “River” brought together three reliable actors – the powerhouse (Sean Penn, who went FTW with Oscar, ousting Bill Murray’s well-deserved nom for “Lost In Translation” in the process), the ambitious character actor and occasional leading man (Tim Robbins, pocketing an Oscar as well) and the 6-degrees-of-separation-inspiring nervy everyman (Kevin Bacon, suspiciously and acceptably toned down). Their intertwined stories, along with a murder investigation led by Bacon and the occasionally slumming Laurence Fishburne, form the crux of a expansive Boston-set boiler that is rooted in the very basic Eastwood theme of vengeance. “Mystic River” is likely to be remembered for Penn and Robbins, who turn in career-defining work, Penn as a grieving father with a criminal past who isn’t afraid to bloody his hands and Robbins as a wrecked man-child forever haunted by a vicious act of abuse. Marcia Gay Harden and Laura Linney, relegated to “wife” territory, deliver terrific performances and guided by Eastwood’s sure hand, the cast and the film involves and occasionally captivates. The multiple plot-lines don’t cohere with the kind of dramatic tension Eastwood might be shooting for but the ending is appropriately chilling and ties the personalities on display here with a grand tear-jerker of wrongly dealt out punishment – not a great film, but a memorable warm-up for the renewed vigor of the Clint Eastwood of the aughts. [B+]

“Million Dollar Baby” (2004)

“Million Dollar Baby” (2004)

It will be difficult to qualify just how much acclaim rewarded to this 2004 Best Picture had to do with tackling a largely unspeakable subject in a sensitive and intelligent way. To reveal the twist (literal and figurative – bad taste, I know) is to bare the heart of the film, which this writer never found to be particularly moving. “Million Dollar Baby” is hardly a departure for Eastwood, the same themes and Catholic guilt resting on the shoulders of Frankie Dunn (Eastwood) – Dirty Harry as boxing gym owner and former manager. Enter Maggie Fitzgerald – Brandon Teena meets Rocky played with grift and no shortage of stubbornness by Hilary Swank, scoring her second Oscar in five years. Yes, Frankie takes on the challenge of Maggie. Yes, he molds her into a fighter to be reckoned with. And yes, Morgan Freeman’s aging pugilist and Frankie’s conscience, watches over the Eastwood and Swank as they slowly rise to the occasion, facing the present while dealing with the sins of the past. Freeman is probably the best thing about the film, warm and all-knowing, and seemingly ever-present. Hmmm… To be frank, revealing the trajectory of Maggie as a human being first and a boxer second would undermine the very element of surprise the film attains on first viewing. So as an admirer, rather than an unabashed fan, this writer would like to say this is a solid film that sticks out in the boxing genre as something unabashedly more earnest, coupled with top-notch performances and painted in somber, funereal tones. [B]

“Flags Of Our Fathers” (2007) & “Letters To Iwo Jiwa” (2007)

“Flags Of Our Fathers” (2007) & “Letters To Iwo Jiwa” (2007)

Easily Clint Eastwood’s most ambitious undertaking of his entire career, the one-two punch of the “Flags Of Our Fathers” and “Letters From Iwo Jima” was supposed to be the grand scale tale of one of World War II’s bloodiest battles from both sides of the trenches. Unfortunately, both pictures were plagued by the same problems: gooey sentimentality, clichéd characters and a sloppy structure underselling whatever impact each film individually or collectively could have had. “FOOF” found Eastwood confronting a number of thematic elements but never quite delivering on the promise of them. Instead the film seems to run out of Eastwood’s grasp and the last third is overloaded with a voice narration that is hardly used in the rest of the film. Simiarly, “LFIJ,” finds itself with the crutch of a flashback heavy narrative and a teary tone that is hammered home instead of earned. Eastwood’s films are almost painfully polite, lacking teeth and direction. The same American soldiers that Eastwood takes pains to humanize in “FOOF” are turned into savages in “LFIJ,” and the reverse is true as well. By the end of it all, Eastwood has made two films that are somber, mature and utterly empty without anything original to say. There is a great single movie somewhere in here that would allow for an interesting perspective on the soldiers, the battle and what was going on both fronts but Eastwood failed to find it in two movies.

“Flags Of Our Fathers” [C]

“Letters From Iwo Jima” [C-]

“Changeling” (2008)

“Changeling” (2008)

Sweet Lord, was there ever a more depressing film in the history of cinema than this vehicle for Angelina “stop trying so hard, love, you’re bound to win Best Actress sooner or later” Jolie? For those who don’t know, and probably spent their time doing something more joyous like filling out tax returns or having their dog put down, the based-on-a-true-story plot revolves around a single mother who does not believe the boy claiming to be her lost son is in fact her missing child. Pitted against the authorities who just want the case closed, she is ultimately committed to an insane asylum, before eventually being vindicated, if that’s the right word, by the discovery of the actual hideous fate of her son. It is not a bad film – not incompetently made, shot, or acted, but in offering us no redemption, no catharsis and none of the retrospective wisdom that surely the intervening years should have lent, it ends up little more than an almost fetishistically cataloged litany of this poor woman’s ordeals. As such it is a wholly masochistic experience: for Jolie, reliving the trauma for (presumably) take after take, for Eastwood attempting to ‘do the story justice’ by refusing to leaven it with even a flash of humor or a moment of levity, and most of all for the viewer, who, for all the good intentions on display will afterward feel rather like they’ve just watched two and half hours of torture porn. Seriously, unless you crave a dull headache and a feeling of misanthropic gloom that will last for days, avoid. [D]

“Gran Torino” (2008) Kevin

“Gran Torino” (2008) Kevin

On the face of it Clint Eastwood’s most recent and probably last starring role, found him playfully taking the piss out of his macho on-screen persona (if there was an Academy Award for Best Growling, Clint Eastwood would’ve locked it up). In “Gran Torino,” what looks on the surface to be a straightforward “racist-guy-learns-to-love” film turns out be something both more simplistic and more complicated than that. Clint’s character is less of a racist than an all around equal opportunity asshole, and even as he befriends the foreign neighbors that initially drive him bananas, he doesn’t suddenly stop using racial slurs or really change much of his attitude. They earn his respect and in turn, he earns theirs. To its credit, the film very carefully navigates some pretty difficult racial and political territory without ever going to the pulpit, and the script earns its emotional punch. That said, this B-level material for Eastwood (it’s essentially a smarter than usual vengeance pic) that doesn’t make any mistakes about where its going in the last part of the film, delivering the weepy ending that seems to be Clint’s specialty, particularly in his late career films. No, its not perfect, but its certainly far more enjoyable and insightful than you might expect. Though hampered by truly bad acting by the supporting cast (particularly Bee Vang, who played Thao), “Gran Torino” earns its stripes by delivering the goods and taking some unexpected, and refreshing detours along the way. [B]

“Invictus” (2009) Morgan Freeman as Nelson Mandela? Well, there’s something that was always gonna happen. It’s just a shame that this perfect, inevitable casting was wasted on such a lackluster film. Part underdog-sports-fable, part political history, out of all the fascinating stories that comprise South Africa’s recent past, “Invictus” tells the ‘true life’ tale of Mandela inspiring and encouraging the (predominately white) South African rugby team to an unlikely World Cup victory. It’s a bizarre choice for director Eastwood, who wouldn’t be known for his rugby fascination, and frankly, it smacks of a cart-before-horse, “I wanna work with Freeman again, I want him to play Mandela, now what projects are there knocking around?”-type decision. Directorial motives aside, the film is really most remarkable for Matt Damon’s performance – he brings a subtlety and depth to a character who is pretty reactionary by Hollywood hero standards, and convinces physically as a rugby captain: even his accent is flawless. But what does it say about the film that it’s Damon, and not Freeman-as-Mandela who is the most memorable thing in it? As ever, Eastwood is restrained and even-handed to a fault — no seriously, it’s a fault here, the film could do with some good, old-fashioned bias to shake it out of its stupor. Instead, it is stately, respectful and loaded with gravitas (a word that Freeman could surely trademark by now), but in aiming for ‘important’ it lands wide of the mark at ‘worthy’ instead. But perhaps even that could be forgiven if we weren’t so distracted by the specters of much more interesting untold stories that lurk around its edges. [C]

“Invictus” (2009) Morgan Freeman as Nelson Mandela? Well, there’s something that was always gonna happen. It’s just a shame that this perfect, inevitable casting was wasted on such a lackluster film. Part underdog-sports-fable, part political history, out of all the fascinating stories that comprise South Africa’s recent past, “Invictus” tells the ‘true life’ tale of Mandela inspiring and encouraging the (predominately white) South African rugby team to an unlikely World Cup victory. It’s a bizarre choice for director Eastwood, who wouldn’t be known for his rugby fascination, and frankly, it smacks of a cart-before-horse, “I wanna work with Freeman again, I want him to play Mandela, now what projects are there knocking around?”-type decision. Directorial motives aside, the film is really most remarkable for Matt Damon’s performance – he brings a subtlety and depth to a character who is pretty reactionary by Hollywood hero standards, and convinces physically as a rugby captain: even his accent is flawless. But what does it say about the film that it’s Damon, and not Freeman-as-Mandela who is the most memorable thing in it? As ever, Eastwood is restrained and even-handed to a fault — no seriously, it’s a fault here, the film could do with some good, old-fashioned bias to shake it out of its stupor. Instead, it is stately, respectful and loaded with gravitas (a word that Freeman could surely trademark by now), but in aiming for ‘important’ it lands wide of the mark at ‘worthy’ instead. But perhaps even that could be forgiven if we weren’t so distracted by the specters of much more interesting untold stories that lurk around its edges. [C]

“Hereafter” (2010)

“Hereafter” (2010)

To essentially paraphrase (or simply rip-off) a brilliant Time Out Review that feels like it was written in our brain before we had a chance to pen it, Eastwood’s strengths — his easy-going approach, his simple clean and natural shooting/editing style — are his weaknesses in this painfully listless supernatural thriller about near-death experiences. Another major deficiency is Eastwood’s unfussy mien. Peter Morgan has already stated that he was surprised to no end when he heard that Eastwood was going into production with what he considered a rough first draft and it shows. While an interesting premise, the picture never gelled or had much of a driving narrative on the page and the film is equally purposeless and seemingly uninterested in its own content. A puffy (and humorless) Matt Damon sleepwalks through his performance as a reluctant clairvoyant (the romance with Bryce Dallas Howard is so half-hearted you wonder why it’s even there) and the picture demonstrates little forward momentum. Irresponsibly unengaging and dull as a rubber knife, the film isn’t bad per se, but acts like a warmly-temperatured room that will likely lull you to sleep. Ironically, this quiet meditation about life and death barely registers a pulse throughout and is essentially lifeless. One of Eastwood’s biggest misfires in a while. [D]

— Kevin Jagernauth, Drew Taylor, Oli Lyttelton, Katie Walsh, Sam C. Mac, Jessica Kiang, Mark Zhuravsky, Rodrigo Perez