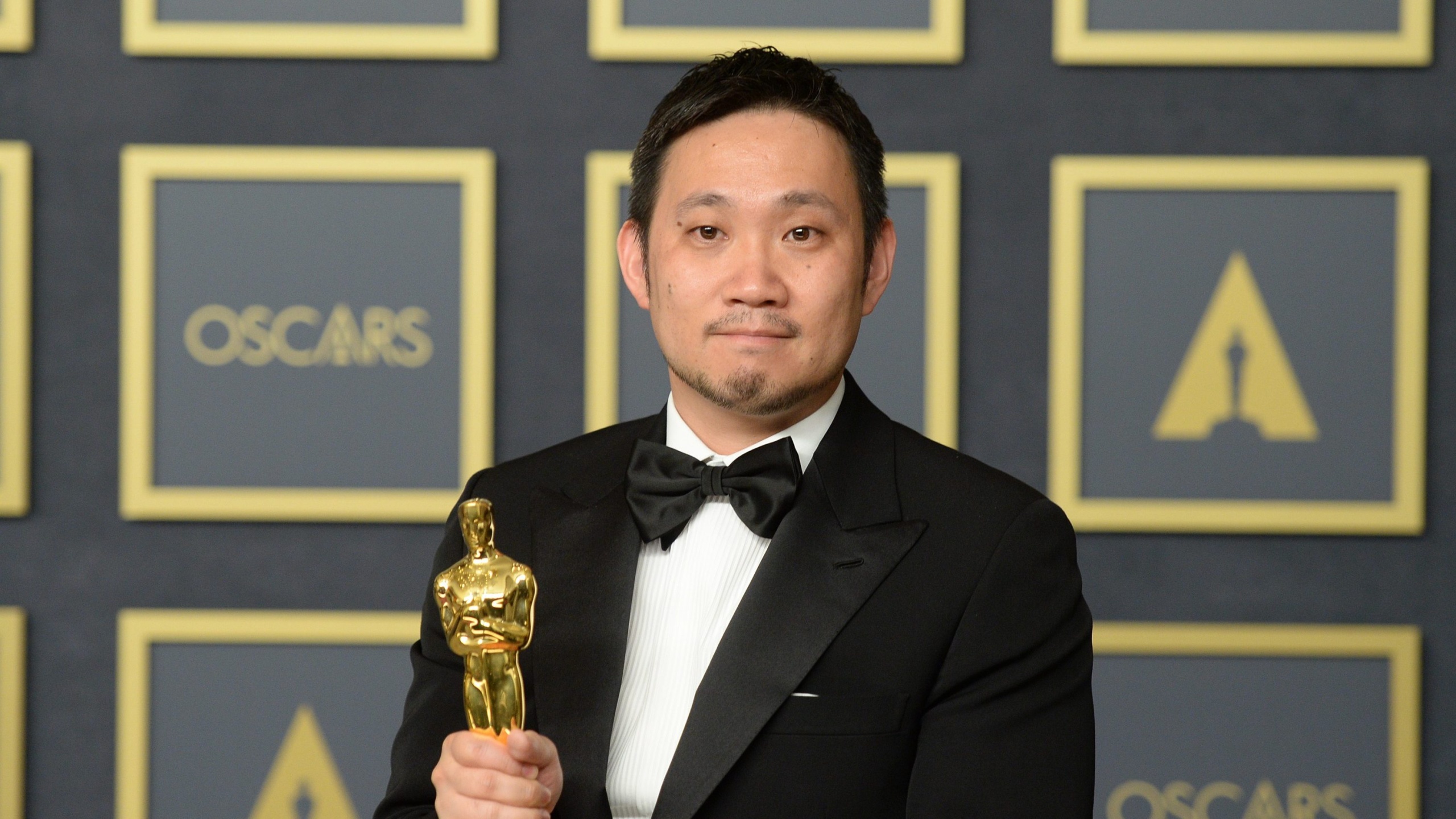

After years of making films in his native Japan, writer-director Ryusuke Hamaguchi found unexpected global success in 2021 with “Drive My Car.”

Adapted and expanded from short stories by Haruki Murakami, it’s an exquisite drama about a grieving theater director staging a multilingual “Uncle Vanya,” and his relationship with the pensive young woman employed to drive his cherry-red Saab.

Premiering at the Cannes Film Festival, where Hamaguchi and co-writer Takamasa Oe won the Best Screenplay prize, “Drive My Car” went on to dominate the fall festival circuit. The film clocked up an astonishing four nominations at the 2022 Oscars, including Best Picture and a Best Director nod for Hamaguchi, and went on to win Japan’s first Oscar for Best International Film.

Hamaguchi’s latest film, “Evil Does Not Exist” is to some extent a response to that overwhelming acclaim. “I knew that I wanted my next work to be very different and that somehow it was going to be important for me,” he said.

The project began when Eiko Ishibashi, the composer of “Drive My Car,” invited Hamaguchi to create a silent film to accompany a live musical performance. From this footage, Hamaguchi fashioned an 18-minute short named“Gift,” then expanded it into a feature film.

Abandoning the urban landscapes of “Drive My Car,” “Evil Does Not Exist” takes place in an isolated rural community, focusing on a widowed settler named Takumi (Hitoshi Omika) and his young daughter Hana (Ryô Nishikawa).

At first, Takami’s life seems idyllic — chopping firewood, collecting spring water from a nearby stream and often forgetting to collect Hana from school, who happily walks home alone through birch forests. Cinematographer Yoshio Kitagawa and sound designer Izumi Matsuno expertly capture the pristine silence and ambient noise of the forest, while Ishibashi’s score underlines the danger lurking beneath those beautiful surfaces.

The community’s serene existence is interrupted when urban developers announce plans to build a luxury camping site, promising big tourist dollars and community regeneration.

Tensions boil over at a town hall meeting with hapless PR reps Mayuzumi (Ayaka Shibutani) and Takahashi (Ryuji Kosaka), where locals express concern about water pollution and increased risks of forest fires. Hamaguchi films the sequence in slow, excruciating detail, registering every beat of the locals’ distrust of the glib corporate-speak of venture capitalism.

Somewhat unexpectedly, Mayuzumi and Takahashi express horror at the damage they’re about to cause. In a long conversation filmed in a moving car (a Hamaguchi specialty), they discuss their discontentment with their jobs and their desire to right wrongs by returning to the community. Evil, it seems, does not exist — all that’s needed to reform corporate greed is fresh air, a forest walk and a warming bowl of udon noodles.

The finale — a shocking and unexplained burst of Kubrickian violence — turns the story on its head. Since the film’s 2023 premiere at Cannes, where Hamaguchi won the Grand Prix, it’s become the most heavily debated ending since Darren Aronofsky’s 2017 eco-horror “mother!” Was evil there all the time, waiting to manifest? Or is violence necessary to correct greater evils?

IndieWire caught up with Hamaguchi, his producer Satoshi Takada and translator Aiko Masubuchi. Our interview feels similar to the play audition scenes in “Drive My Car” — intense concentration, long patient silences as Aiko translates back and forth, and repeated nods and murmurings of “Arigatō” (thank you).

Much like his films, Hamaguchi is reserved, scrupulously polite and in no hurry to explain himself, but genuinely fascinated by the responses to his work.

IndieWire: Congratulations on “Evil Does Not Exist,” which is a wonderful film. The film is very specifically Japanese but also feels like a parable that could be set anywhere. Was it your intention to create a story that could resonate internationally?

Ryusuke Hamaguchi: I wasn’t conscious about wanting to have the film resonate internationally. I am an urbanite. I work and live in a city, and the film deals with water pollution issues arising outside of the city, which is not close to my ordinary life. However, the town hall meeting in the film was based on something that actually happened. When I heard about that, I thought about how nature has the ability to recuperate when it is given time, but when capitalist ventures happen, problems arise when there’s not enough time to replenish. That’s something that happens in my own life and in the film industry. When you build a [shooting] schedule, and don’t take into account the time for the crew to recuperate, that’s when overwork issues arise. Other places in the world that rely on similar systems also experience the same issues.

So much of the film is about the waste we create — the evil we create — often without knowing it. Takumi talks in the town hall meeting about how balance is key. Your film seems both optimistic and pessimistic about balance being achieved, particularly in a capitalist society.

I think balance is the most difficult thing to achieve because it requires [us] to do two things going in different directions at the same time. It’s a theme I grapple with myself in my own life and in my filmmaking. When I make films, I have to think about the balance of how to make fiction out of reality. If it’s pulled into fiction too much, I might lose what is more lifelike about the reality that exists. The same thing can be said about actors’ performances. When it’s too close to reality, a certain kind of fiction can no longer be told. We’re required to grapple with those two ideas in order to make it work.

Speaking of balance, the success of “Drive My Car” launched you into a very long awards campaign, which I imagine took you away from your creative work. How did that experience affect your filmmaking choices for “Evil Does Not Exist”?

Due to the release of “Drive My Car” and “Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy” in the same year, I was almost engaged in a year-long series of promotions, which was indeed exhausting. After the Oscars, I took about a half-year break. I received the request from Ms. Ishibashi at the end of 2021, before winning the Oscar, and started moving around the end of 2022, thinking it was about time to get going. When I was working on the production, I was engrossed in it and focused solely on that, because of the trust Ms. Ishibashi had in me. Being able to concentrate on what I find interesting was very beneficial for my mental health. Being honest with my own senses is something I feel will be the foundation of my activities going forward.

The film has an intensely poetic style, like a fairy tale, but the town hall sequences could be out of a Frederick Wiseman documentary.

I made a documentary about 10 years ago [“Storytellers,” 2013] about storytellers who tell folk tales. Often, those stories are telling something that can’t be said directly. Of all the films I’ve made, “Evil Does Not Exist” is perhaps closer to one of these folk tales. They have this ability to show something that is complex and not quite ethical. I think my own kind of storytelling has become closer to that feeling.

Your use of color in the film is remarkable. Hana’s yellow gloves and Takahashi’s bright orange coat are so out of place in the rural landscape. They almost work as warnings, like traffic lights, that something is wrong.

As I was making this film within a natural landscape, there were many things I couldn’t control, including the weather. I also knew I needed some way to make Hana and Takahashi stand out and move within the frame of the film without it being contrived. The story has documentary and fiction elements that intermingle with each other.

Takahashi and Mayuzumi are city dwellers selling this sanitized experience of nature but don’t pay attention to the natural world. They could have been villains, but you show so much compassionfor themand make them fully rounded human beings.

I am also a city dweller, so I understand the logic behind how they end up doing something that they don’t want to be doing. But to me, that’s different from whether I empathize with the characters. That leads me to think about Douglas Sirk’s films, where you love and hate the characters at the same time. There’s a part of me that empathizes with them, but then I also reject them. That back-and-forth process leads to being able to achieve a more balanced perspective.

This is the second time you’ve worked with Aiko Ishibashi. Can you talk about working with her to develop this project?

She’s the person who brought up the project and led it along. This film was really a result of me trying to write to her music. The fact that this film has no clear conclusion is really the result of her music, and the sensitivity and violence that exists within it.

Which films would you program to be watched alongside “Evil Does Not Exist”?

To be honest, I wish somebody else would think of films [that are a] good accompaniment! [Laughs] Since we mentioned Wiseman earlier, there is a similarity in the town hall scene to Wiseman’s documentary “Boston City Hall.” I wasn’t consciously trying to replicate this, but I was happy to realize there’s a similarity between this scene and the film. And Douglas Sirk, especially “Written on the Wind.” The use of yellow in the film, especially the sports car at the beginning, [is echoed in] Hana’s yellow gloves. And Ozu’s “Tokyo Story,” which is my favorite film.

“Evil Does Not Exist” opens in U.S. theaters on Friday, May 3from Sideshow/Janus Films.