Like so many cyberpunk movies before it, Jérémie Périn’s ultra-cool and dazzlingly animated “Mars Express” is sustained by the vertigo between the boundlessness of computer technology and the banality of what people do with it. What separates this accomplished French “Ghost in the Shell” homage from its most obvious touchstone — and from several other detective stories in which a police team of people and androids investigate what it means to be human — is the film’s determination to dismantle that dynamic.

Much less nakedly philosophical than anything Mamoru Oshii has ever made, “Mars Express” is nevertheless fascinated by the future that artificial intelligence might choose for itself if it were unshackled from the limits of our mortal imaginations (and from the anxieties that come along with them). Périn is humble enough to only half-guess at an answer, but his steadfast conviction that humans and robots could mutually inhibit the other’s potential allows this hacker whodunnit to become more than the sum of its most recognizable parts. That’s even as it spends the brunt of its 89-minute running time scrambling to build a well-furnished sci-fi world around the scaffolding of its basic — yet still hard-to-follow — murder-mystery plot.

Yes, the assassination of a not-so-random college student in her dorm is somehow connected to a cybernetics trillionaire and a conspiracy that has the power to reshape life on multiple different planets. By the time “Mars Express” arrives at its final destination, however, its most familiar elements have reluctantly given way to a vision of tomorrow in which people aren’t fated to become more robotic, and robots aren’t doomed to repeat the mistakes of the people who made them.

But first: The kind of introduction that Oshii fans might recognize from an episode of “Stand Alone Complex,” as Mars-based detective Aline Ruby (voiced by Morla Gorrondona in GKIDS’ phenomenal English dub) and her android partner Carlos Rivera (Josh Keaton) visit Earth to ensnare a notorious hacker named Roberta (Sarah Hollis). The year is 2200, and our home planet has been reduced to “a swamp for the unemployed” as artificial intelligence has widened the gap between the haves and have-nots to an interplanetary degree. Robots serve at the behest of the rich, and jailbreaking them free of their programming is among the most serious of crimes.

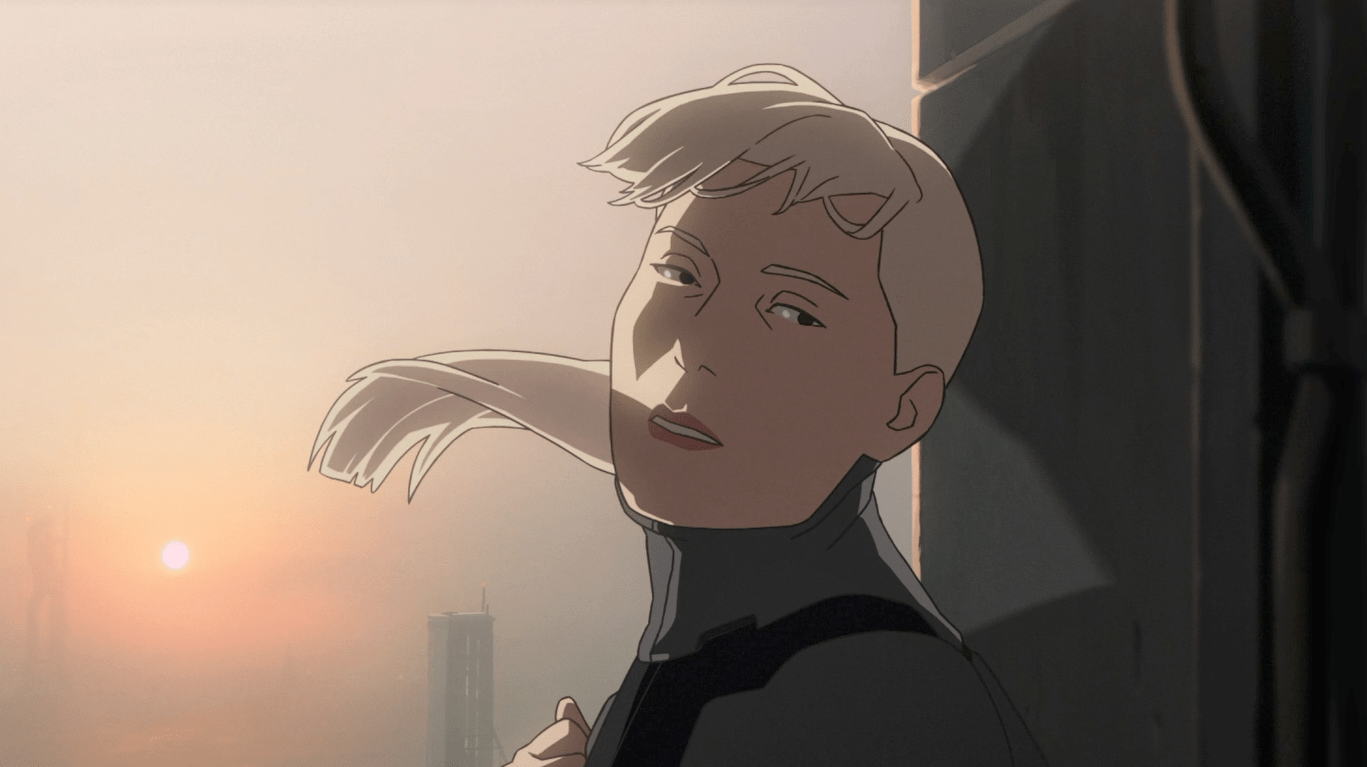

Take Carlos, for example: He actually died in a war several years earlier, but his memories and personality have been uploaded into an exoskeleton that his disembodied head floats above like the dot of an “i.” He’s free to do his job, and to pay some tenderly uncomfortable visits to his ex-wife, but rigid, Asimov-like rules prevent him from striking her aggro new husband. Carlos poses as Roberta’s latest customer, the hacker gets wise to the trap, and Aline — a sexually frustrated recovering alcoholic who has to override the sobriety chip embedded under her skin in order to have a drink — launches into a chase that Périn uses to show off his film’s sleek but visceral techno-future. It blends glossy CGI surfaces with hard-lined character designs to create a visual aesthetic that reflects the film’s uneasy synthesis between organic and constructed worlds.

Mars looks seductively idyllic, its residents living under a dome of screens that hide the darkness of space behind a digital recreation of the French Riviera, but the people living there bleed and cry and otherwise betray the fact that we bring ourselves with us wherever we go. Much of the film’s unique charm is owed to the naturalism that Périn and Laurent Sarfati’s busy script demands from its characters, as well as the actors voicing them; “Mars Express” is filled with sighs, “ums,” and other small human moments that might be stamped out from the more arch examples of its genre, and the robots emulate that casualness in a way that makes it hard to tell if they’ve been set free or if they’re simply getting becoming more like people.

In some cases, it’s almost impossible to spot the difference. Jun, the student targeted for assassination at the start of the story, is revealed to have an illegal android doppelganger. It’s typically the kind of thing that rich kids buy to help them do better in school, while less privileged students pay their tuition by renting their brains out to people who want to leech off the information they’ve learned in class (Jun’s socioeconomic status is more complicated than we first realize).

The film is filled with such details (e.g., synthetic sex workers, newfangled memory drugs, organic AIs that float in fish tanks like brains in formaldehyde and stink up the room), but “Mars Express” often moves too fast for viewers to appreciate their relevance to Aline and Carlos’ investigation fully. The plot is easy enough to appreciate in broad strokes, as the film’s gripping and unusual action sequences clearly widen the scope of the drama and bring us closer to connecting the dots between Jun’s attempted murder and the potentially inhabitable new planet we keep hearing about on the news. But the specifics of how one thing relates to another tend to be slippery at best.

So far as Périn is concerned, that’s more of a feature than a bug — one that allows his movie to skirt over the finer points and focus instead on the liminality of the world around them, a sort of Schrödinger’s future where everything and everyone is both alive and dead at the same time, and also neither. The film’s most expressive image is a shot of Carlos’ translucent floating head as he walks away from his family; look at his face, and you see his ex and their daughter visibly crying behind it. Technology has compelled the world to ingest itself rather than move forward, and the same technology that has allowed humanity to spread itself into the stars is also keeping them anchored to the past.

“Mars Express” may have benefited from the luxury of being able to slow down (this story could have easily sustained a 13 or 26-episode anime season), but Périn makes the most of its propulsiveness, as this eye-popping movie launches toward a future where tech might be liberated from the people who created it. When it comes to AI and whatnot, our imaginations typically default to fears that reflect our own anxieties and desires; “Mars Express” doesn’t pretend that our concerns are out of place (a throwaway line hints at the irreparable economic damage AI has caused), but it breathes new life into its formulaic genre by focusing instead on what technology might want for itself, and finds a shimmering measure of beauty in the idea that the things we build might eventually travel into the furthest reaches of our solar system without having to carry our baggage along for the ride.

Grade: B

GKIDS will release “Mars Express” in theaters on Friday, May 3.