In the 1952 book “Mere Christianity,” C.S. Lewis argued that the most logical case against atheism was the notion that humans born in completely unrelated civilizations during every era in history all entered the world with the same internal feeling that someone above us is displeased with our conduct — and that we should make some kind of sacrifice to earn their favor back. Just like our thirst leads us to water and our hunger leads us to food, he argued that our guilt and cravings for atonement were natural urges pointing us all towards the same hope for transcendence. But in Jordan Scott’s “A Sacrifice,” Ben Monroe (Eric Bana) has a considerably simpler interpretation of the same premise: “When someone mentions sacrifice or redemption, I smell cult.”

As a bestselling author, visiting professor, and expert in the field of social psychology, Ben knows a thing or two about how cults get started. But he’s not nearly as competent when it comes to the simpler — but not easier — task of keeping his family together. Years of disagreements about parenting ensured that his marriage ended in divorce, and he relocated to Europe with the hope that a little distance might help his broken family grow closer. It hasn’t exactly worked out that way, and by the time his teenage daughter Mazzy (Sadie Sink) shows up on his doorstep to spend a semester with him, she’s had plenty of time to reach the conclusion that her dad has completely and irreparably ruined her life.

Ben might have hoped that a few months in Berlin together would afford them plenty of opportunities for father-daughter bonding, but he soon gets sucked into the kind of professional opportunity that, in his words, only comes around once in a lifetime. His colleagues at the university enlist his help looking into a charismatic spiritual leader who has become something of a wellness rock star in Berlin with her book and soliloquies about the way human isolation is eroding modern society. Young people feeling disillusioned with the promises (or lack thereof) that society has to offer them keep flocking to her speeches about how humans aren’t designed for the individualistic lives we’ve been conditioned to live. The clear answer to our malaise, the new cult members will be quick to tell you, is sacrifice. That spiritual sacrifice takes the form of elaborately choreographed group suicides that spin death as the ultimate liberation from the grind of human existence.

The appeal of a group that makes little effort to hide its interest in suicide is a puzzling intellectual question — one that takes up so much of Ben’s time that he hardly notices that his daughter has started partying with a boy she met on the train. When Mazzy finally goes missing, Ben is forced to confront the possibility that his own focus on professional glory might have driven his daughter into the very group he was determined to stop.

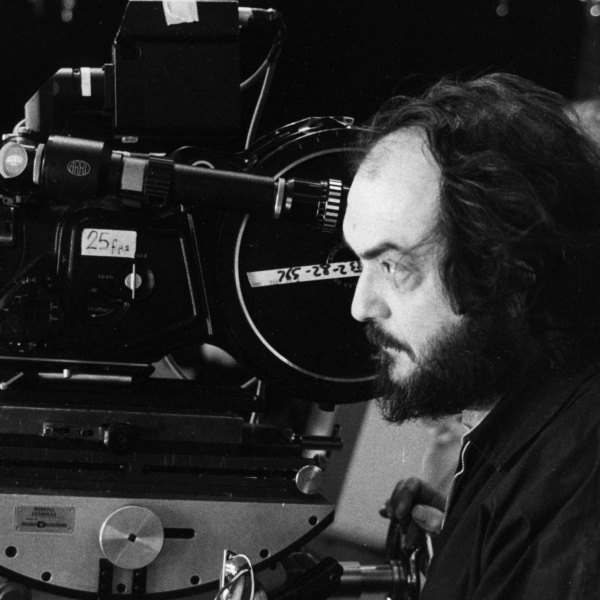

Jordan Scott’s film, adapted from Nicholas Hogg’s novel “Tokyo Nobody” and produced by her father Ridley, isn’t quite as interesting as the towering questions that it asks. But the fact that it bothers to ask them at all puts the film in a rarified class above many of its Hollywood counterparts. At a certain point there’s only so much riffing you can do on the tension between secular humanism and our primordial thirst for the divine before you have to land the plane on a 94 minute father-daughter thriller. At least strong performances from Sink and Bana — along with sleek, noir-infused cinematography from Julie Kirkland — make for a pleasant viewing experience even when the intellectualism comes up short.

Still, what lingers after the film ends isn’t a particular plot point or shot, but the deep sense that our society hasn’t engaged with these questions any more deeply than the film has. Scott wisely casts a magnifying glass on the fine print at the bottom of any utopian manifesto, which stipulates that lofty musings about freeing ourselves from the destructive impulses of human nature aren’t much use when the people asking us to trust them with our lives are bound by the same instincts that we are. And while the temptation to dismiss religion as a bunch of uninformed fairy tales haunts all of us at one point or another, “A Sacrifice” illustrates that the alternative is seldom much of an improvement. Maybe G.K. Chesterton was onto something when he wrote “When men stop believing in God they don’t believe in nothing; they believe in anything.”

Grade: B

A Vertical release, “A Sacrifice” opens in theaters on Friday, June 28.