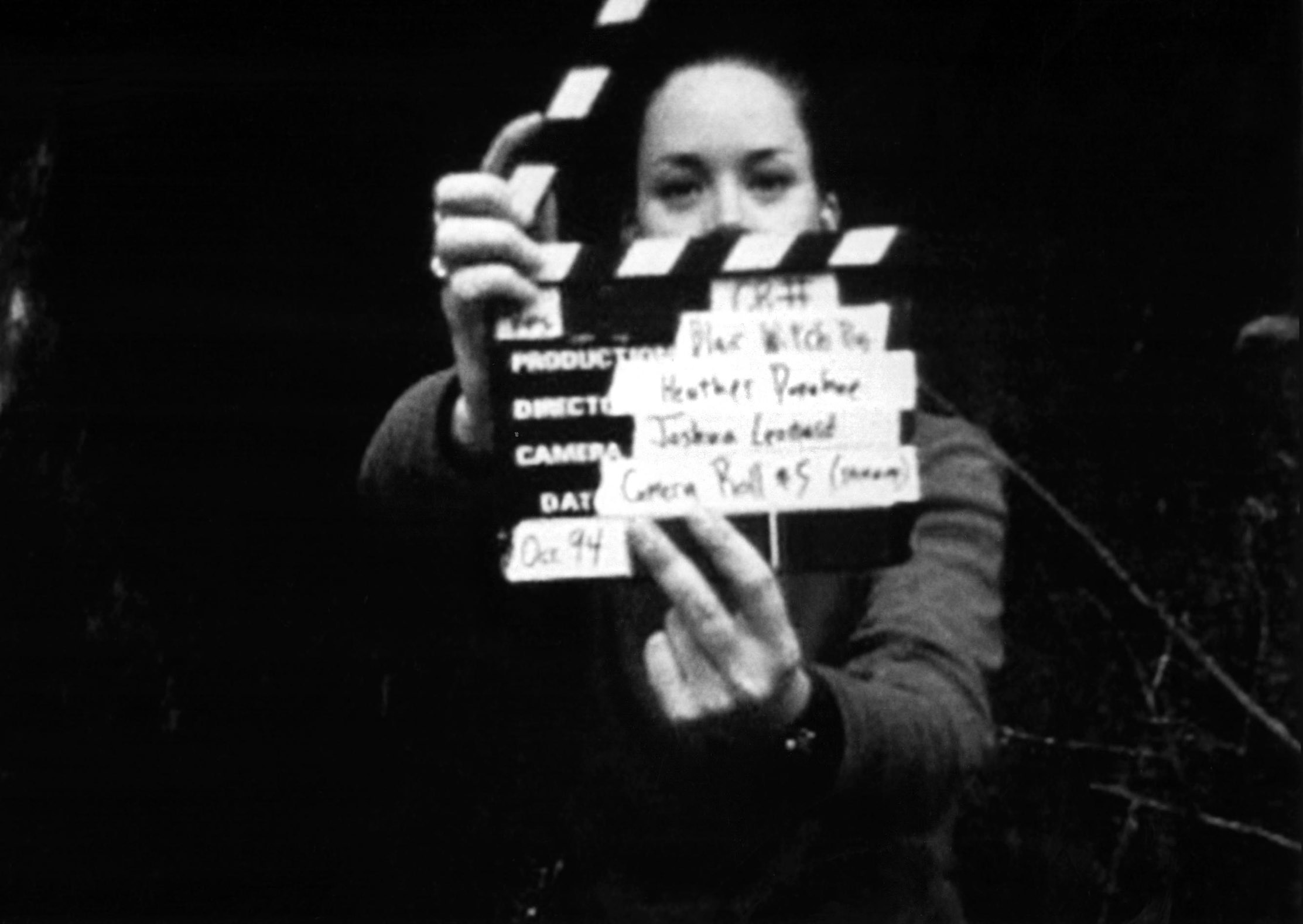

In October 1994, three student filmmakers disappeared in the woods near Burkitsville, Maryland while shooting a documentary. A year later, their footage was found.

That brief but iconic introductory text and the narrative that followed would captivate millions for decades. When “The Blair Witch Project”hit theaters in summer 1999, moviegoers were enthralled by the ill-fated fictional journey of three would-be documentarians — Heather Donahue (Rei Hance), Josh Leonard (Joshua Leonard), and Mike Williams (Michael Williams) — hunting down the truth behind a local Maryland myth. It was shocking; the analog realism of the then-obscure found footage genre instilled in viewers the sense that what they were witnessing was the last record of a real tragedy. The illusion was made even more palpable thanks to a marketing campaign that embraced the early internet with a rudimentary website, missing persons posters of the characters, and a TV mockumentary companion, “Curse of the Blair Witch,” that preceded the film’s release.

In the years since, the “Blair Witch Project’s” impact on the horror genre is as strong as it’s ever been, and the vision crafted by writer-directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez can still be detected in the DNA of what came after. Its influence has birthed modern-day hits like the “Paranormal Activity”franchise and indie fare like the “V/H/S”series. Even though a couple of sequels, like “Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2” (2000) and “Blair Witch”(2016), have tried to capture the thrill of the original, nothing’s come close to the original sensation. That hasn’t stopped studios from trying. At this year’s CinemaCon, Blumhouse and Lionsgate announced a reboot was in the works despite dissatisfaction from the original cast who are seeking retroactive compensation for their past work and consultation on the project.

For a generation of horror fans and filmmakers, that manic trek into the woods, and the haunting final scene, is as good now as it was a quarter of a century ago. For the 25th anniversary of “The Blair Witch Project,” IndieWire reached out to some of horror’s new class of filmmakers about the movie’s enduring legacy, their first impressions, and sentiments years later.

The following interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jane Schoenbrun (“I Saw The TV Glow,” “We’re All Going to the World’s Fair”)

In terms of the movie’s influence, the language and tropes it established, they’ve just been done to death. When I was researching my first film, “We’re All Going to the World’s Fair,” and engaging with a later community on the internet and finding the creepypasta world where literally hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of kids are ripping off “Blair Witch” or ripping off a ripoff of “Blair Witch.”

“Blair Witch” had this sort of “I have a camera, so I’m gonna go into the woods with my friends and act really scared” cultural lexicon that anyone could create for themselves, almost like a campfire story.

So I think with my own work, I understand the magic and joy and campfire beauty of that feeling. I think my work is in conversation with it.

“The Blair Witch Project” invented this genre, but like musicians who sort of invent a thing that then becomes its own genre. When you watch the movie that created the rules back before the rules existed, there’s usually like a magic there that transcends the cliches. It’s not like just the first example of cliches. There’s something pure in it.

Heather [Donahue]’s performance in that movie is incredible. It’s pretty heart-wrenching stuff. It’s emotionally visceral in a way that I think few horror movies are. Pure emotional horror.

She is an amazing actor, and I think it was so parodied to death. Especially that iconic monologue where she’s crying and whimpering to the camera. It became almost this like cultural punching bag or just a shorthand for something that was satirized to death until it became impossible to decouple it from that parody. And the ending is so restrained, and so sparse that really does presage the cursed image tradition of the internet and the creepypasta realm and what can now be classified as sort of analog horror like “Skinamarink.”

I remember very clearly going into the computer room at my childhood best friend Chris’ house and looking up the website. I remember us loading the trailer and watching that, which included the night vision audience reaction to the movie… and I remember waiting like 20 or 30 minutes for that two-minute trailer to load, probably in terrible quality.

There’s something festive about it in this very early internet way. I knew that the movie was fictional, and also the meta narrative that it was real that was part of this marketing campaign’s intention was very exciting in this very specific way that I don’t think I’ve experienced before. I remember watching that trailer and just kind of getting lost in the festivity of that intentional confusion of what we’re watching.

Robert Eggers (“The Witch,” “The Lighthouse”)

I was in high school when “The Blair Witch Project” was released so I had already established the New England horror mythology of my imaginary landscape. But it echoed many of the things that I had thought of, imagined and experienced, which is why it was effective for me.

Growing up in rural New Hampshire, we have colonial American history drummed into us to some degree. You could certainly ignore it, but as someone who found history interesting and exciting I did not. The old dilapidated colonial houses, barns, and cemeteries were all around. Colonial gravestones with folk carvings of skulls and angels were something you could see any day. My father was a Shakespeare professor, and I understood that there may have been people walking around in the woods behind my house that grew up during the reign of Queen Elizabeth, I could easily imagine them. With witches specifically, I become frightened of witches beginning with Margaret Hamilton as a small child. Of course, a great deal was made of the Salem witch trials at school and they fascinated me. I think, unlike vampires or werewolves, evil witches could be real, they aren’t creatures — they are humans. What was that old woman down the lane in the hoarder house doing in there (we asked ourselves as children)?

The first time watching it I was totally gripped. And I grew up in a house in the middle of the woods off a dirt road, so I had many occasions to be familiar with what it’s like to be alone and afraid in the woods. The BWP is instructive on how much you can do with so little, a lesson I certainly applied in my first feature, “The Witch.”

Zach Cregger (“Barbarian”)

We heard that there’s footage of these people dying. I got it on a blank VHS tape, and I remember I watched it with some friends, and it scared the fucking shit out of me. It had been dubbed and dubbed and dubbed and dubbed… so it looked really decayed and was out of focus all the time. I would have “Blair Witch” parties at my house where like kids I wasn’t even that close to it would come over. I would have like eight people in my basement and because I had this special tape, we would watch it. It was like an event.

I had never seen a movie like that, so it definitely expanded my horizons of what is capable of being categorized as a 90-minute narrative film. It just feels so convincingly real and authentic, like a true documentary. They pulled it off in that way. The actors delivered fantastic performances.

In the last 10 years, there’s been a real boon [with the horror genre] because I think there’s room right now for horror to blossom in a fresh way. This is really depressing, but I think it’s because of the collapse of, I hate to use the word cinema, but Hollywood is not making that much anymore that is risky and feels urgent — except in the horror space.

Hollywood has just kind of become this top-heavy superhero-driven spectacle machine. The only room for a weird, challenging movie to go into the theaters is with genre. Because people will show up and put their butt in the seat. We all like to be scared at the same time.

Adam Wingard (“Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire,” 2016’s “Blair Witch”)

This is going to sound like kind of blowing things out of proportion or whatever, but it does feel like there really is an actual curse that goes along with it. I’ve never had a production where everything just went so wrong all the time.

One thing that I haven’t had a chance to share with anybody… during the pandemic, I saw that it was playing on TV, and I’ve never actually watched any of my movies with commercial breaks before. As I was halfway through it, I had to use the bathroom. So I get up to go to the restroom, and I walk in there, and all the cabinets in the bathroom were open. All the drawers and the cabinets were like just standing open. I never had anything supernatural happen to me while I was living at that house; It was just the one time that I happened to watch “Blair Witch.” Never again.

Nia DaCosta (“The Marvels,” “Candyman,” “Little Woods”)

I went to boarding school in high school, and I was in a dorm. I think I was 16, by myself, wrapped up in covers… And I was like, “Let me just watch this movie. I’ve never seen it.” Sometimes you watch a film that’s, like, the scariest movie ever made and then you watch it and it doesn’t hold up to being scary. I was freaked the fuck out. I don’t know if it’s because my school was in Westchester, surrounded by woods.

We always have stories about ghosts and whatever that lived in the dorms and stuff. So I was freaked out. I was also super impressed. I was like, “Wow, this is like, genuinely fucking scary. It was great.”

[Urban legends] tap into our magical thinking. Instead of something positive and sweet and inoffensive as believing in astrology, you believe in an axe murderer with a hook for a hand. I think it taps into our propensity, everyone’s propensity, for magical thinking, and I think the magical thinking part of it comes from like, “Well, maybe there was a guy who was in the projects killing a bunch of people.” When you look at the history of those buildings that the first movie was set in, like, that shit happens.

But it wasn’t like a ghost or a demon. It was just a human being. It’s the way we’ve been telling stories since the beginning of time. We didn’t call it urban legends then, but that’s how we’ve explained the horror that we lived through.

If “The Blair Witch Project” came out now, for example, we’d go on to IMDb, we’d see their IMDb pages, we’d see all the things they’ve been in before, we’d see the production company and who owns the production company.

Everything is online. Every truth and lie is on the internet. I think when it’s a creepypasta, there’s no author, there’s nothing to find, there’s no IMDb page, there’s no studio history or whatever. When it’s a film now, the institution is so laid bare to the public… I think we might be out of that era a bit or we have to be more creative about how we trick the audience into not knowing exactly what we’re doing.

Jeff Wadlow (“Imaginary,” “The Curse of Bridge Hollow,” “Fantasy Island”)

I think it came out at a time when it was able to capitalize off internet buzz and sort of the notion of going viral — even though I think going viral wasn’t an expression back then — but it wasn’t really able to be hurt by all the haters that are now online. Do you know what I mean?

So like it kind of came out at this perfect moment from a marketing standpoint and I remember it was just a sensation. I can vividly recall talking to friends about whether or not it was real, which is just crazy if you think about it in hindsight. I mean, we’re talking about college educated, 20-somethings debating whether or not “The Blair Witch Project” was a real documentary. It’s just absurd in hindsight, but at the time it was a legitimate question. And I just thought it was really cool and seemed very powerful. And honestly, without “Blair Witch,” there is no “Paranormal Activity.” And without “Paranormal Activity,” there is no Blumhouse. It directly affected me as a filmmaker because I’ve made three movies for Jason [Blum] now, and I love playing in that space. And in that sense, we owe it all to “Blair Witch.”

When I saw it, I was fascinated. I mean, again, it was the first time I’d seen a found footage movie and that expression didn’t exist. I had obviously seen other mock documentaries like “Spinal Tap,” so I was aware of the kind of mockumentary subgenre, but I’d never seen it done to such a terrifying effect where the camera becomes a character in the piece. It’s evocative of “Rear Window” almost in that sense, where the camera is becoming you, the audience, and in a very literal way. From a filmmaking standpoint, I was really into it and taken with the notion.

Also, I was a little scared of it, too. I mean, I thought it could be very limiting as a filmmaker. Like, what do you mean you can’t cut to the master? What do you mean you can’t use inserts or cut to coverage so you’re making sure you’re seeing your characters’ faces? It was a little scary, but I was super into it and also started trying to come up with my own found footage ideas afterwards.

Sometimes, you’ll see a scary movie, and they won’t show you the monster, and it feels cheap because they’re using omniscient coverage. It’s like, “Well, why am I not seeing the monster? It doesn’t make any sense.” You need to back it up. You need to have a rationale for why the monster is not seen… What “Blair Witch” did so well is they use the idea that the camera is a character.

So you’re limiting your view to just this really. And so it’s a lot easier to not show the monster when this very small aperture is your view. So I think in that sense, they took that trope and they embraced it in a very organic way and used it incredibly effectively because of the found footage format.

Kyle Edward Ball (“Skinamarink”)

The first time I watched it, I watched it on a 15-inch television on VHS in my parents’ room. The TV was really high up with terrible sound, and I remember being very disappointed, actually. And so then I revisited it as a teenager, like, I don’t know, maybe 18, 19 years old, launched it on a big screen with a nice sound system, and it was like I really hadn’t heard the movie before

I wouldn’t say when I first saw it as a kid that I hated it, but I just didn’t necessarily see the hype, and it was because I didn’t watch it properly, right? The visuals and concept were intriguing, but I was underwhelmed. And then when I saw it as a teen, I fell in love with it and then kept falling in love with it over and over again so that it’s turned into my comfort movie. I watched it probably 50, 100 times or something, like I don’t know the exact number. So it’s been a journey.

People will often say things like, “Oh, ‘The Blair Witch Project,’ you couldn’t necessarily do a viral marketing campaign like that today because of social media,” or this and that. People would clue into it right away that the actors were real actors. The thing is though, you maybe could do it better today because you can misinform people so easily now. People seem so gullible now. And you can manipulate people very well, so maybe you could do the “Blair Witch” today, right? Someone could post something saying, “Oh these are real actors, here’s their IMDb,” and then someone would rebut it or bury it in quote retweets, so, who knows?

It’s interesting — and incredibly surreal and flattering — hearing all the similarities between how “The Blair Witch Project” blew up and how my movie [“Skinamarink”] blew up, particularly in the word-of-mouth aspect.

There’s something magical about horror and word of mouth, right? If someone goes up to you and says “No you have to see this. It is so fun. It’s weird,” and they explain it a certain way. It has a bigger impact than the best cut trailer possible. There’s a certain magic to “I know this person. I know their movie tastes and they’re vouching for it,” right?

The other interesting thing is how the internet has even kind of changed the definition of what word of mouth is, because it used to literally be word of mouth and now word of mouth can be TikTok, right? That’s kind of another interesting aspect.

Oren Peli (“Paranormal Activity”)

“The Blair Witch Project” showed how an incredibly scary movie can be done with a bit of ingenuity, and not a lot of resources. Having a strong and believable cast is key, especially for a found-footage format where they need to improvise the dialogue, and appear as real people, not actors. They showed that you can create scarier moments by not showing the “monster,” and also the importance of sound to help mess with the audience’s imagination. They showed that you can take your time building suspense, and don’t need to play by the rules of the movies dominating at the time that relied on gore and jump-scares. Also, for a found-footage movie, the most important thing is that it is authentic. Even if it means the cinematography and sound are compromised in quality, that’s actually necessary for the movie to be believable.

The good thing about found footage is that it’s affordable to make, and everyone with an idea can make a found-footage movie. The bad thing about found footage is that it’s affordable to make, and everyone with an idea can make a found-footage movie.

That is to say, we’ve seen a few really great found-footage movies come out in recent years, but also many that unfortunately were not. However, I’m still a sucker for found-footage so I’ll watch many of them since I enjoy the format. For me, anything that’s done in a realistic and authentic style will always be more effective than a “traditional” film. I believe that found-footage movies are here to stay.

Eugene Kotlyarenko (“Spree”)

The commercials had this weird quality where you knew it was an ad for a movie, but then they told you it was an amateur film from three kids who disappeared in the woods, and doubled down when they showed some clips that truly looked like shit. It stuck out. The website also was like the first movie website that I remember being advertised everywhere. When you went to it, it kept up the same charade: This is a movie but also here are all the details about the dead filmmakers and the company that edited the footage (the credited directors), etc. I thought that was genius.

I’m sure every filmmaker my age has put a poster or still from “The Blair Witch Project” into their first (and maybe even second) pitch deck, trying to raise money for their film, and teasing the possibility for investors (and you have to believe it a little, too) that your movie was going to be the next “Blair Witch.”

The proto-virality of the marketing definitely seeped into my subconscious. I’d been doing a bit of conceptual social media marketing for my previous two films (“A Wonderful Cloud” & “Wobble Palace”), but with the nature of “Spree” as a Livestream and the central character a wannabe influencer, I felt I could really go all the way this time. Joe Keery and I made lots of videos to get into character before the shoot and then got together a few months after our Sundance premiere to film a bit more material. From this, and a bunch of DIY memes, we were able to construct an entire universe of content and then post it in character on the @kurtsworld96 Instagram account.

Since [“Spree”] has a commentary, I tried to make sure the arc of the account leading up to the release had a similar schizoid vibe that fluctuated from innocence to megalomania, obliviousness to psychosis. Engagement with the account was incredibly active leading up to the release, and pretty convincing in creating a little bit of the mythology around the film. I assume everyone knew it was fake, but I hoped the kids were having a similar feeling as me when I looked at the IMDb page for “Blair Witch.”